The Constitution Act, 1867 was originally known as the British North America Act (BNA Act). It was the law passed by the British Parliament on 29 March 1867 to create the Dominion of Canada. It came into effect on 1 July 1867. The Act is the foundational document of Canada’s Constitution. It outlines the structure of government in Canada and the distribution of powers between the central Parliament and the provincial legislatures. It was renamed the Constitution Act, 1867 with the patriation of the Constitution in 1982.

Confederation

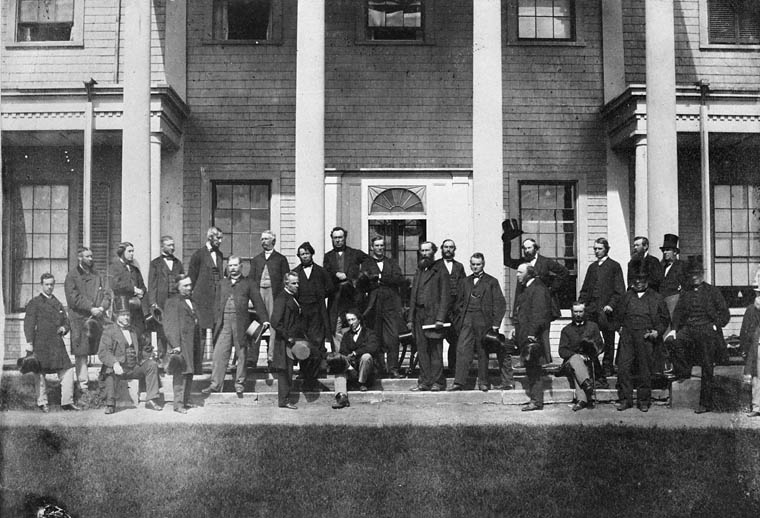

The BNA Act was enacted by the British Parliament on 29 March 1867. It came into effect on 1 July 1867. It provided for the union (confederation) of three of the five British North American colonies into a federal state with a parliamentary system modelled on that of Britain. The three colonies were Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and the Province of Canada (which was divided into Ontario and Quebec).

Rupert’s Land was acquired in 1870. Much of that region became Canada’s first territory, the Northwest Territories, which was established in 1870. Six provinces have since been added to the original four: Manitoba (1870), British Columbia (1871), Prince Edward Island (1873), Alberta (1905), Saskatchewan (1905) and Newfoundland (1949). Two more territories were also added: Yukon (1898) and Nunavut (1999).

The Constitution Act, 1867 does not contain the entire Constitution of Canada. The Act is complemented by British and Canadian statutes that have constitutional effect (e.g., the Canada Elections Act) as well as certain unwritten principles known as constitutional conventions. These include the power vested in the Crown to dissolve Parliament and call a general election. They are usually exercised on the advice of the prime minister.

Distribution of Powers

The Act outlines the distribution of powers between the central Parliament and the provincial legislatures. (See also: Federal-Provincial Relations; Quebec Resolutions.) For example, section 91 gives Parliament jurisdiction over areas such as banking, interest, criminal law, the postal system and the armed forces. It also gives the federal government power over "Indians and Lands reserved for the Indians." (See also Indian Act.) Section 92 gives the provinces jurisdiction over areas such as property, most contracts and torts, local works, undertakings and businesses.

The Act describes legislative powers in general terms. As a result, direct conflicts sometimes arise in areas where provincial and federal laws regulate the same thing. When such conflicts occur, federal law prevails. In the case of powers that are exercisable by both jurisdictions, federal law prevails in matters involving agriculture and immigration (section 95). Provincial law prevails in old-age pensions (section 94A).

New fields and areas that arise — e.g., radio broadcasting, aeronautics, official languages — are given to the federal government. The federal power of peace, order and good government embraces such areas. It also includes matters that fall under “national dimensions” and “emergencies.” (See also: War Measures Act; Emergencies Act.) The term “national dimensions” mean that certain matters within provincial jurisdiction can become subject to federal jurisdiction if the circumstances warrant it. For example, during an epidemic, authority over day-to-day health care can shift from the provinces to the federal government. In wartime, virtually all provincial powers may come under federal control.

In 1976, the Supreme Court of Canada decided that Parliament also possesses what amounts to a peacetime emergency power; this allows it to impose national wage and price controls to combat serious national inflation. (See also Anti-Inflation Act Reference.) Unlike the US constitution, which treats all states as equal, the Constitution Act, 1867 does not suggest that all provinces are constitutionally equal. For example, the Prairie provinces, unlike the original four provinces of Confederation, did not possess rights to their natural resources for 25 years after becoming provinces.

Court Interpretations

Judicial decisions have had a substantial effect on provincial and federal powers. Until 1949, appeals had to be made to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in Britain. These judges often favoured provincial powers when they came into conflict with federal powers. These included areas such as property law and civil rights; peace, order and good government; and the regulation of trade and commerce. The British judges sought to offset the excessive centralism they perceived in the BNA Act (such as the federal veto over any provincial statute in section 90) while still preserving a viable federal system.

Since 1949, the Supreme Court of Canada has pursued a more centralist interpretation. In 1980, the lack of a domestic amending formula in the BNA Act led to a constitutional crisis. Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau tried to patriate the Constitution from Britain without provincial consent. In September 1981, the Supreme Court decided that his proposal was unconstitutional. (See Patriation Reference.) Trudeau relented, and “patriation” was finally achieved in April 1982 with federal-provincial consensus.

See also: Constitutional History; Constitutional Law; Peace, Order and Good Government; Constitution Act, 1867 Document; Statute of Westminster; Statute of Westminster, 1931 Document; Patriation of the Constitution; Constitution Act, 1982; Constitution Act, 1982 Document.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom