Cree are the most populous and widely distributed Indigenous peoples in Canada. Other words the Cree use to describe themselves include nehiyawak, nihithaw, nehinaw and ininiw. Cree First Nations occupy territory in the Subarctic region from Alberta to Quebec, as well as portions of the Plains region in Alberta and Saskatchewan. According to 2021 census data, 223,745 people identified as having Cree ancestry and 86,475 people speak Cree languages.

Origin of the Term “Cree”

The name Cree originated with a group of Indigenous peoples near James Bay whose name was recorded by the French as Kiristinon and later contracted to Cri, spelled Cree in English. Most Cree use this name only when speaking or writing in English and have other, more localized names.

Population and Territory

(courtesy Native Land Digital / Native-Land.ca)

In the 2021 census, 223,745 people identified as having Cree ancestry. Cree live in areas from Alberta to Quebec in the Subarctic and Plains regions, a geographic distribution larger than that of any other Indigenous group in Canada. Moving from west to east, the main divisions of Cree, based on environment, language and dialect are Plains Cree (paskwâwiyiniwak or nehiyawak) in Alberta and Saskatchewan, Woods Cree (sakâwiyiniwak) in Saskatchewan and Manitoba, Swampy Cree (maskêkowiyiniwak) in Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Ontario, and James Bay/Eastern Cree (Eeyouch) in Québec; Moose Cree (in Ontario) is considered a sub-group/dialect of Swampy Cree. The suffix –iyiniwak, meaning people, is used to distinguish people of particular sub-groups. For example, the kâ-têpwêwisîpîwiyiniwak are the Calling River People, while the amiskowacîwiyiniwak are the Beaver Hills People.

The Eastern Cree are closely related, in both culture and language, to the Innu (Montagnais-Naskapi) and Atikamekw. Many Cree First Nations in western provinces have blended populations of Ojibwa, Saulteaux, Assiniboine, Denesuline and others. In addition, the Oji-Cree of Manitoba and Ontario are a distinct people of mixed Cree and Ojibwa culture and heritage. Many Métis people also descend from Cree women and French Canadian fur traders and voyageurs. (See also Fur Trade.)

Traditional Life

For thousands of years, the ancestors of the Cree were thinly spread over much of the woodland area that they still occupy. Known as the Ndooheenou (“nation of hunters”), the Cree followed seasonal animal migrations to obtain meat for food and animal hides and bones for the making of tools and clothing. They travelled by canoe in summer, and by snowshoes and toboggan in winter, living in cone- or dome-shaped lodges, covered in animal skins. (See also Architectural History of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.) Many Cree still consider hunting an important part of their culture and way of life; the hunting and trapping of moose, caribou, rabbit and other animals is fairly common in Cree communities.

After the arrival of Europeans, participation in the fur trade pushed Swampy Cree west into the Plains. During this time, many Cree remained in the boreal forest and the tundra area to the north, where a stable culture persisted. They continued to rely on hunting moose, caribou, smaller game, geese, ducks and fish, which they preserved by drying over fire. The Cree also traded meat, furs and other goods in exchange for metal tools, twine and European goods. Plains Cree exchanged the canoe for horses, and subsisted primarily through the buffalo hunt.

Society

Cree lived in small bands or hunting groups for most of the year, and gathered into larger groups in the summer for socializing, exchanges and ceremonies. They historically had cultural, trade and social relations with other Algonquian-speaking nations, most directly with the Innu (Montagnais-Naskapi), Algonquin and Ojibwa.

Although the Cree strived to maintain a communal and egalitarian society, some individuals were regarded as more powerful, both in the practical activities of hunting and in the spiritual activities that influenced other persons. (See also Shaman.) Leaders in group hunts, raids and trading were granted authority in directing such tasks, but otherwise the ideal was to lead by means of exemplary action. Some of the most well-known Cree chiefs and leaders include Mistahimaskwa (Big Bear), Pitikwahanapiwiyin (Poundmaker) and Piapot — all of whom strove to maintain traditional ways of life in the face of change after the arrival of Europeans.

Culture

The Cree participated in a variety of cultural ceremonies and rituals, including the Sun Dance (also known as the Thirst Dance, and particularly celebrated by the Plains Cree), powwows, vision quests, feasts, pipe ceremonies, sweat lodges and more. Many of such rituals were banned by the Indian Act until 1951; however, the traditions survive to this day.

One of such ceremonies is the “walking out ceremony” — a ritual in which children are officially welcomed into the community. Cree tradition dictates that children’s feet are not to touch the ground outside of a tent until the ceremony takes place. Therefore, the ritual is usually held as soon as a child is able to stand or walk on their own. The morning of the ceremony, the child — dressed in traditional clothing — awaits the arrival of the Elders. Once they arrive, the Elders send the child outside of the tent. Accompanied by an adult, the children walk around a designated area outside the tent. Usually, they are told to mimic hunting or other traditional roles of adults. Once they have done this, the children re-enter the tent and give the Elders gifts. The community gathered inside the tent embraces the children as new members of their society. A feast usually follows.

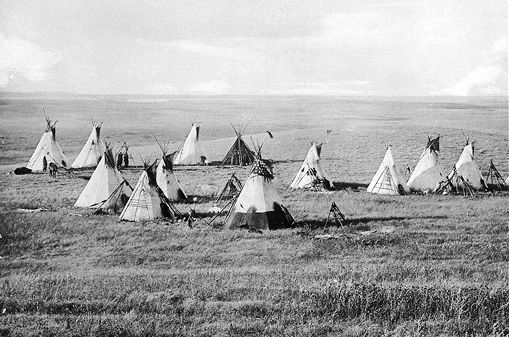

Art and music are important elements of Cree culture. Well-known for their beadwork, Cree women created beautiful and functional clothing, bags and furniture. Plains Cree peoples also decorated the outsides of their tipis with paint. A well-known modern Cree artist is George Littlechild. Drumming is significant to the Cree as well as to most other Indigenous nations. Drums are sacred, and the music that comes from them is likened to the heartbeat of the nation. Drum music can be heard at festivals and religious ceremonies.

Religion and Spirituality

The Cree worldview describes the interconnectivity between people and nature; health and happiness was achieved by living a life in balance with nature. Religious life was based on relations with animal and other spirits which often revealed themselves in dreams. People tried to show respect for each other by an ideal ethic of non-interference, in which each individual was responsible for his or her actions and the consequences of those actions. Food was always the first priority, and would be shared in times of hardship or in times of plenty when people gathered to celebrate by feasting.

The Cree worldview also incorporates Trickster (wîsahkêcâhk) mythology. A trickster is a cultural and spiritual figure that exhibits great intellect, but uses it to cause mischief and get into trouble. The Cree believe one can learn important lessons about how to live — and not to live — good lives from the examples set by the tricksters. One common trickster figure in Cree spirituality is Wisakedjak — a demigod and cultural hero that is featured in some versions of the Cree creation story. (See also Religion and Spirituality of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.)

Origin Story

Cree stories tell about the past as well as about their belief system. Every Cree nation has a slightly different version of the creation story, but they often have common elements, such as the presence of the Creator or Great (Kitchi/Kitche) Manitou. The following is a paraphrased version of a creation story as recorded by the explorer and geographer, David Thompson:

At the beginning of time, the Creator made the animals and the people. The Creator told Wisakedjak (a trickster figure) to teach the people how to live good, peaceful lives, and to take care of them. Wisakedjak did not listen to the Creator, and soon, the people were fighting and hurting one another. The Creator was disappointed and threatened Wisakedjak with a life of misery if he did not obey. Still Wisakedjak did not listen, and still the people continued to be violent with one another. The Creator decided to flood the lands, washing out everyone and everything. Only Wisakedjak, Otter, Beaver and Muskrat survived. Stranded on open water, Wisakedjak had an idea — if the animals could help him dive down and collect some of the old earth, he could expand it and start a new land. This was not an easy task; Otter and Beaver tried many times to get to the earth below, but both failed, almost dying in the process. Muskrat was the last to try. He stayed underwater for a long time, but when he resurfaced, he had wet earth in his paw. From this mud is where the earth as we know it today came.

Language

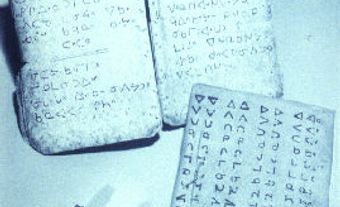

The Cree language belongs to the Algonquian language family, and is in itself a continuum or family of dialects. Depending on the region, some Cree peoples speak a slightly different version of the language than Cree peoples in another area. The closer the speakers’ communities are, the more likely they are to understand one another. For example, the Eastern Cree dialect is more closely related to the Innu language, and is therefore less intelligible (understandable) to western dialect speakers, such as the Plains Cree.

In 2021 Statistics Canada reported 86,475 people speak Cree languages, including Plains Cree, Woods Cree, Swampy Cree, Northern East Cree, Moose Cree and Southern East Cree. Cree is one of the most widely spoken Indigenous languages in Canada, along with Inuktitut and Ojibwe. The majority of Cree speakers live in Saskatchewan, Alberta and Manitoba.

Michif, the language of the Métis, is influenced in part by Cree; Cree heavily influences Oji-Cree, which is also influenced by Ojibwe. In 2021, Statistics Canada reported 1,845 Michif speakers and 15,210 Oji-Cree. Atikamekw, a language closely related to Cree, was reported as having 6,740 speakers.

Colonial History

Jesuit missionaries first mentioned contact with Cree groups in the area west of James Bay around 1640. Fur trading posts established after 1670 began a period of economically motivated migration, as bands attempted to make the most of the growing fur trade. For many years, European traders depended on Indigenous people for fresh meat. Gradually, an increasing number of Cree remained near the posts, hunting and doing odd jobs and becoming involved in the church, schools and nursing stations. Missionizing began when some fur traders held services; trained Christian missionaries soon followed.

During the late 1700s and the 1800s, Cree who had migrated to the Plains changed with rapid, dramatic success from trappers and hunters of the forest to horse-mounted warriors and bison hunters. Epidemics, the destruction of the bison herds and government policies aimed at forcing First Nations to surrender land through treaties, however, brought the Plains Cree and other “horse-culture” nations to ruin by the 1880s. (See also Numbered Treaties.) The Canadian government, under the leadership of Sir John A. Macdonald, actively withheld rations and other resources in order to force starving Plains peoples into signing treaties and relocating to reserves. There, Cree existed by farming, ranching and casual labour, and were subjected to further cultural destruction through decades of trauma endured in the residential school system.

Though the government made general promises to protect Cree land rights and their traditional way of life, the treaties gave the federal and provincial governments the power to intervene in Cree traditional culture. Government services, health programs and education, including residential schooling, were usually administered through the missionaries and traders until the middle of the 20th century.

Contemporary Life

Government-backed corporate exploitation of natural resources in the 20th and 21st centuries has brought radical changes in many Cree communities. In the 1970s in Quebec, the James Bay Cree successfully negotiated the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement. The agreement was a response to the James Bay hydroelectric project, which had been undertaken without consultation of the communities it would affect. The project pushed the James Bay Cree to action, and the resulting agreement provided the first step toward self-government. Since then, a series of further agreements between the Cree in Quebec, the provincial government and the federal government have followed. The Cree have also been central to United Nations negotiations, including the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007).

Many registered members of Cree nations no longer live in their reserve communities. Nevertheless, for many nations, especially in the James Bay and Plains regions, the portion of registered members living on reserve is very high. For example, the rate of population living on reserve among James Bay Cree averaged 83 per cent in 2015, reaching 96 per cent in the case of Whapmagoostui.

Self-government and economic development are major contemporary goals of the Cree. Cree First Nations across Canada have attempted to negotiate with development corporations and governments. For example, the Lubicon First Nation of Alberta have sued the provincial and federal governments for their share of natural gas revenues and further recognition of treaty rights, while in Manitoba, several Cree nations have reached agreements with the federal and provincial governments, as well as resource companies.

Several Cree leaders have had a national role in furthering the aims of Indigenous peoples in Canada, including Assembly of First Nations chiefs Noel Starblanket, Ovide Mercredi, Matthew Coon Come and Perry Bellegarde, and Attawapiskat chief Theresa Spence, who gained national attention for her involvement with the Idle No More movement in 2012 and 2013.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom