In a monarchy, the Crown is an abstract concept or symbol that represents the state and its government. In a constitutional monarchy such as Canada, the Crown is the source of non-partisan sovereign authority. It is part of the legislative, executive and judicial powers that govern the country. Under Canada’s system of responsible government, the Crown performs each of these functions on the binding advice, or through the actions of, members of Parliament, ministers or judges. As the embodiment of the Crown, the monarch — currently King Charles III — serves as head of state. The King and his vice-regal representatives — the governor general at the federal level and lieutenant-governors provincially — possess what are known as prerogative powers; they can be made without the approval of another branch of government, though they are rarely used. The King and his representatives also fulfill ceremonial functions as Head of State.

History

Monarchical government has existed in what is now Canada since 1534. At that time, Jacques Cartier claimed land in what is now Quebec for King François I of France, an absolute monarch. (See Monarchism.) Following the conquest of New France and the Treaty of Paris in 1763, New France was passed to Britain, a constitutional monarchy.

In 1848, Nova Scotia established responsible government. (See Nova Scotia: The Cradle of Canadian Parliamentary Democracy.) In this system, ministers selected from elected representatives govern in the name of the sovereign and are held to account by the legislature (similar to a modern Cabinet). The Province of Canada (present-day Ontario and Quebec) also adopted responsible government in 1848. It was granted in other Maritime provinces in the 1850s.

According to the Constitution Act, 1867, “The Executive Government and Authority of and over Canada is hereby declared to continue and be vested in the Queen.” As such, Canada’s system of government was modeled on Britain’s. The British Crown served as a unifying principle in Canada’s Confederation. Shared loyalty to the monarch brought together provinces with very different political interests. (See Ontario and Confederation; Quebec and Confederation; New Brunswick and Confederation; Nova Scotia and Confederation.)

The Statute of Westminster (1931) codified the divisibility of the Crown. The Dominions — semi-independent states such as Canada, Australia and New Zealand — continued to share a common monarch. (See Commonwealth.) But she or he would only act on the advice of the ministers of each Dominion for matters concerning those individual nations. When George VI and Queen Elizabeth made their Canadian tour in 1939, they toured as King and Queen of Canada. Queen Elizabeth II was the first monarch to be crowned Queen of Canada, in 1953.

Canada’s constitution was patriated in 1982. This ended the British Parliament’s power to legislate for Canada. Paragraph 41a of the Constitution Act, 1982 states that changes to “the office of the Queen, the Governor General and the Lieutenant Governor of a province” may only take place with the unanimous consent of the Senate, the House of Commons and the Legislative Assembly of each province. This structure for amendment entrenched the Crown in Canada’s constitutional framework. (See also Constitution Act 1982: Document.)

Parliament

Canada’s Parliament is comprised of the Crown (monarch), the Senate and the House of Commons. Each institution must agree with a given law before it is enacted. The government of the day acts in the name of the Crown, which is largely a symbolic and ceremonial institution; but the government derives its authority from the Canadian people who elected it. It is therefore a “representative” government.

Parliament has two branches: the executive, including the Crown, prime minister and Cabinet; and the legislative, including the House of Commons and the Senate. In each of the 10 provinces, the legislature consists of the lieutenant-governor and the members of the elected assembly. (See Members of Provincial and Territorial Legislatures.)

The current system of parliamentary democracy under the Crown emerged from the councils that advised medieval English monarchs. The earliest took place in 1265; it contained noble representatives from cities and boroughs. As parliamentary representation expanded, common citizens were included in parliament. This was the case by 1295. The right to vote gradually expanded to include widespread male ;suffrage in the 19th century and women’s suffrage in the 20th century.

The Sovereign

The current sovereign of Canada is King Charles III. The sovereign retains certain prerogative powers under the Constitution Act, 1867. These powers are almost always exercised with the advice of the prime minister. The Ming's powers to appoint and dismiss the prime minister; to summon, prorogue and dissolve Parliament; and to grant royal assent to legislation have been either delegated to or conferred upon the governor general. This was accomplished by the Letters Patent, 1947 and the Constitution Act, 1867. The Crown’s other prerogative powers are exercised by the Governor-in-Council (Cabinet acting through the governor general). These powers include the authority to grant pardons and to ratify treaties. When the sovereign is present in Canada, particularly on historic occasions, she or he can exercise the Crown’s constitutional powers in person.

According to 19th-century constitutional theorist Walter Bagehot, the rights of a constitutional monarch include the right to be consulted; the right to encourage; and the right to warn. In turn, vice-regal representatives also retain these rights; they can exercise them in meetings with first ministers (the prime minister and premiers).

The Governor General

According to the Letters Patent, 1947, the governor general can exercise all of the sovereign’s powers; except for the appointment of the governor general. The Letters Patent does not change the monarch’s status as Head of State; but it does give the governor general the authority to act as Head of State both domestically and internationally.

The duties of the governor general include representing the monarch in Canada; acting as Commander in Chief; and representing Canada both nationally and overseas. The governor general also recognizes the achievements of Canadians by presenting a wide range of awards (e.g., the Order of Canada; the Order of Merit; the Order of Military Merit). The duties of the governor general are undertaken by lieutenant-governors at the provincial level. In the territories, territorial commissioners represent the federal government. They perform similar duties to lieutenant-governors.

Critiques and Defenses of the Crown

Canada’s system of constitutional monarchy has been critiqued in recent decades. The royal succession is determined by the 1701 Act of Settlement. It restricts the position of sovereign to the Protestant descendants of Sophia of Hanover (mother of King George I). The position of Canada’s Head of State is therefore restricted to members of a single, non-resident family and religion. The importance of the Crown as a ceremonial level of government has also been a matter of debate.

Advocates of Canada’s constitutional monarchy contend that critiques of constitutional monarchy are often based on misconceptions about the Crown’s role in Canadian government. Arguments in favour of the current system of government include the successes of constitutional monarchies around the world, according to measures set by the United Nations Human Development Index. Others argue that maintaining a level of government that is above party politics helps constitutional monarchies lessen partisan divisions.

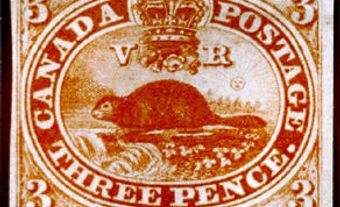

See also Crown Land; Crown Corporation; Crown Attorney; King’s Counsel; Privy Council; Emblems of Canada; Symbols of Authority.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom