Adolphus Egerton Ryerson, Methodist minister, educator (born 24 March 1803 in Charlotteville Township, Norfolk County, Upper Canada; died 18 February 1882 in Toronto, Ontario). Egerton Ryerson was a leading figure in education and politics in 19th century Ontario. He helped found and edit the Christian Guardian (1829) and served as president of the Methodist Church of Canada (1874–78). As superintendent of education in Canada West, Ryerson established a system of free, mandatory schooling at the primary and secondary level — the forerunner of Ontario’s current school system. He also founded the Provincial Normal School (1847), which eventually became the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE). Ryerson also served as principal of Victoria College, which he helped found in 1836 as the Upper Canada Academy. Since about 2010 there has been controversy about his influence on the development of residential schools.

Early Life and Family

Egerton Ryerson was born into a prominent Loyalist family in 1803. His father, Joseph Ryerson, was an officer in the American Revolutionary War (1775–83). He left for Canada and settled as a half-pay officer near Vittoria, Upper Canada, in the 1790s. During the War of 1812, Joseph fought against the Americans, as did his three oldest sons. Egerton grew up in Norfolk County among those who were deeply loyal to Great Britain. He attended the London District Grammar School in Vittoria.

Marriages and Personal Life

In 1828, Ryerson married Hannah Aikman in Hamilton. She died in 1832, soon after the birth of their second child. For a time, family members helped to care for the children, John and Lucilla Hannah. John died of dysentery in 1835 at age six. Lucilla died of consumption in 1849 at age 17. In 1833, Ryerson married Mary Armstrong in York (Toronto). Together they had two children, Sophia in 1837 and Charles Egerton in 1847.

Methodism

Egerton Ryerson’s father, Joseph, belonged to the Anglican Church, but his mother, Mehetable Stickney Ryerson, had Methodist inclinations. (Methodism began as a movement within the Anglican Church. It became a separate church in 1795.) Egerton absorbed his mother’s Methodist sympathies, which were reinforced by the teachings of travelling Methodist missionaries (also known as circuit riders), who preached evangelical Christianity.

Ryerson’s mother joined the Methodist Church in 1816, along with two of his brothers, to the disappointment of his Anglican father. Several years later, when Ryerson applied for membership in his local Methodist society at age 18, his disapproving father insisted that he leave home. For two years (1821–23), Ryerson worked as an assistant to his brother George, who was schoolmaster at the London District Grammar School. Egerton returned home for a short time in 1823. He then left for Hamilton to attend the Gore District Grammar School to study law.

After recovering from a severe illness that interrupted his studies, Ryerson’s commitment to the Methodist faith grew. In 1825, he became a Methodist missionary. He rode on horseback on the York and Yonge Street circuits and lived as a missionary at the Credit River (now Mississauga). There, he worked and lived alongside Ojibwa people. He learned to speak the language and became a respected teacher. He befriended Kahkewaquonaby (Sacred Feathers), also known as Peter Jones, the first Indigenous Methodist missionary. He and Kahkewaquonaby remained close friends throughout their lives. In 1826, at a council meeting, Ryerson received the Ojibwa name Cheechock (Bird on a Wing).

Ryerson first came to prominence in 1826 when he published a public rebuttal against the Church of England. The Anglican Church claimed to be the official church of the colony and exclusive beneficiary of the Clergy Reserves (a portion of lands set aside by the Constitutional Act of 1791 for the support of Protestant clergy). Ryerson wrote a counterattack to an argument by Anglican bishop John Strachan that Methodists were pro-American and therefore disloyal to Britain. Ryerson thus emerged as a leading voice for the Methodist Church.

In 1827, Ryerson was fully ordained as a minister of the Methodist Episcopal Church. He emerged as the leading Methodist spokesman and was a major figure in the Reform cause for religious freedom. He was the first editor of the Methodist newspaper, The Christian Guardian, and used the press to promote Methodism. He continued as an influential political adviser for the rest of his life. Between 1874 and 1878, he served as president of the Methodist Church of Canada.

Politics

Ryerson based his long and active public career on a consistent yet often misunderstood political outlook. His views were a mix of loyalty to British-Canadian institutions; a conservative mistrust of radical philosophy; a liberal optimism in humankind; and a deep and abiding religious commitment.

In Ryerson’s early career, politics in Upper Canada was polarized by Tory and Reform controversy. Ryerson was condemned for not belonging neatly to either camp. He opposed the Family Compact (which was led by Anglican bishop John Strachan and Chief Justice John Beverley Robinson). He also sympathized early on with William Lyon Mackenzie’s ideals of civil equality such as the secularization of the Clergy Reserves.

However, Ryerson publicly criticized the Reform movement in the mid-1830s, since he believed it had become too radical. He also opposed Mackenzie’s violent methods in the rebellion of 1837. During the 1840s, Ryerson continued his active role in politics. Much to the anger of his Reform allies and many Methodists, he supported Governor Charles Metcalfe against Reformers Robert Baldwin and Louis-Hippolyte LaFontaine in 1844. He appeared to have joined the Tories, whom he had opposed for nearly 20 years. He was considered for a role in Metcalfe’s administration and was ultimately offered the role of superintendent of education for Canada West. He fit naturally into the moderate, Liberal-Conservative alliance after the mid-1850s. In fact, he helped create its ideological framework through the educational system he fostered.

Education Reform: Common Schools

In 1844, Ryerson was appointed superintendent of education for Canada West. He held this post until retiring in 1876. In 1844 and 1845, he toured Europe to study different school systems. Based on his findings, he wrote his Report on a system of public elementary instruction for Upper Canada (1846). In this report, Ryerson recommended improvements to the educational system, many of which were adopted in the first two Common Schools Acts (1846, 1850).

By Education, I mean not the mere acquisition of certain arts, or of certain branches of knowledge, but that instruction and discipline which qualify and dispose the subjects of it for their appropriate duties and employments of life, as Christians, as persons of business, and also as members of the civil community in which they live.

Egerton Ryerson, Report on a system of public elementary instruction for Upper Canada (1846)

Ryerson believed that poverty should not be a roadblock to education and that Canada West should have a free and mandatory public education system. “The branches of knowledge which it is essential that all should understand, should be provided for all, and taught to all,” he wrote. Education “should be brought within the reach of the most needy, and forced upon the attention of the most careless.” Ryerson felt education was the most effective way to prevent “pauperism [poverty], and its natural companions, misery and crime.”

He believed strongly that schools should be founded on religion and morality; all students should therefore be instructed in Christian “truth and morals,” but not sectarian dogma. Ryerson wrote at length on the importance of moral instruction, quoting in one instance American educator and clergyman Rev. Dr. Alonzo Potter: “Talents and knowledge are rarely blessings either to the possessor or to the world, unless they are placed under the control of the higher sentiments and principles of our nature.” He further quoted Philipp Emanuel von Fellenberg, creator of the Hofwyl School for the Poor in Switzerland: “Education … embraces the culture of the whole man, — with all his faculties, — subjecting his senses, his understanding, and his passions to reason, to conscience and to the evangelical laws of the Christian Revelation.”

In addition to religious and moral instruction, Ryerson recommended that students at common schools learn the following subjects: reading and spelling; writing, arithmetic, grammar, geography, linear drawing, vocal music, history, natural history, philosophy, natural philosophy, agriculture, chemistry, human physiology, civil government, and political economy. Ryerson regarded these subjects as practical, and necessary preparation for “common” life. “The age in which we live,” he wrote, is “eminently practical [and] scarcely an individual among us is exempt from the necessity of ‘living by the sweat of his face.’” Therefore, he argued, “every youth of the land” should be “trained to industry and practice.”

This new educational system, the forerunner of Ontario’s current school system, would be overseen by the chief superintendent of schools, who would set common standards across Canada West. Ryerson recommended an efficient system of school inspections to maintain these standards. He also recommended standard textbooks across the system and the creation of an Educational Depository, which supplied textbooks and educational material to schools at affordable prices. A Journal of Education was created to help keep teachers up to date.

Ontario gained a new, accessible education system based on these principles. They culminated in the Ontario School Act of 1871, which established free and mandatory schooling.

Teacher Training and Postsecondary Education

Ryerson was one of the founders of the Provincial Normal School (1847), the first teacher’s college in Toronto. It later became the Toronto Teachers’ College and then the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE).

Ryerson also promoted denominational universities as the pinnacle of the educational process. He believed that both the individual and society could be improved through religion and education. Ryerson was a driving force behind the Methodist Church’s establishment of Upper Canada Academy in Cobourg in 1832. In 1841, it became a university and was renamed Victoria College. The following year, Ryerson was appointed principal. He taught at the college and was remembered by former students as an intelligent, exacting and occasionally severe teacher. By 1892, ten years after Ryerson’s death, Victoria College was integrated into the University of Toronto. The campus then moved to Toronto.

During his long career in education, Ryerson wrote numerous pamphlets and texts, as well as an autobiography and several works on the history of the province. He also served as editor of the Journal of Education for Upper Canada between 1848 and 1875.

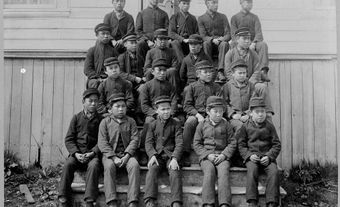

Ryerson and Residential Schools

Since about 2010, Ryerson’s connection to residential schools has been the subject of controversy. At the heart of this debate is a report he wrote in 1847 at the request of the Indian Affairs department. A few years prior, the Bagot Commission (1842–44) recommended manual labour boarding schools as the most effective way to achieve self-reliance and assimilation of the Indigenous population. The intent was to educate and train Indigenous children to become Christian farmers; as such, the schools should have farms and the children should be taught animal husbandry, domestic economy and mechanical trades. (The commission also addressed Indigenous land rights and proposed restructuring of the Indian department.)

By the mid-19th century, manual labour, or “industrial” schools, had been established in Europe and the United States to educate and train poor children. Moreover, boarding schools were not a new idea in Canada, and residential facilities for Indigenous students had existed in New France since the 17th century. The first boarding school for Indigenous children in Upper Canada began operating in Brantford in 1831. In the 1830s and forties, Ojibwa Methodist leaders like Kahkewaquonaby (Peter Jones) and Shawundais (John Sunday) also promoted the idea of boarding schools, pledging money to their establishment and operation. In 1846, government officials met with Ojibwa chiefs, most of whom agreed to fund manual labour schools by donating one-quarter of their annuities (treaty payments).

In 1847, the Indian Affairs Branch of the government asked Ryerson to write a report on the best methods of establishing and operating manual labour schools. As Ryerson understood it, the aim of the schools was to produce “industrious farmers.”

Agriculture being the chief interest, and probably the most suitable employment of the civilized Indian, I think the great object of industrial schools should be to fit the pupils for coming work as farmers and agricultural labourers, fortified of course by Christian principles, feelings and habits.

Ryerson, Report on Industrial Schools (1847)

He therefore recommended that Indigenous students be educated in separate, agriculturally based boarding schools with religious and English language instruction. The schools would provide an education on par with common schools. Ryerson recommended calling the institutions “industrial schools” rather than manual labour schools to encourage both physical and mental industry. (Ryerson’s short report was published more than 50 years later as an appendix to a larger document entitled Statistics Respecting Indian Schools (1898).)

Like many of his contemporaries, Ryerson believed that religious instruction was necessary for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous children. Religious instruction was essential in the industrial schools, he argued, “not merely upon general Christian principles,” but also because “the North American Indian cannot be civilized … except in connection with … religious instruction [and] religious feelings.” He proposed that the schools be run by religious organizations and overseen by the government. Ryerson recommended that each school have a superintendent — “who ought to be the spiritual pastor and father of the family” — as well as a farmer and a schoolmaster. He based his proposal for these industrial schools on the Hofwyl School for the Poor in Switzerland, which he had visited in 1845 and referenced in his Report on a system of public elementary instruction for Upper Canada (1846) as well.

Ryerson proposed that in the summer, students would work 8 to 12 hours a day in various agricultural and domestic tasks, with the remaining hours occupied by religious devotion, meals, and academic lessons; in the winter, students would work fewer hours and devote more time to study. Academic subjects would include reading and English language, arithmetic, elementary geometry, history, geography, writing, drawing, music (especially sacred vocal music), bookkeeping, agricultural chemistry, and religion and morals.

Ryerson also proposed allocating a small payment per day of work, with the sum given to students upon graduation — but only if they demonstrated good conduct and proper bookkeeping throughout their education. “It would be a gratifying result,” Ryerson wrote, “to see graduates of our industrial schools become overseers of some of the largest farms in Canada, nor will it be less gratifying to see them industrious and prosperous farmers on their own account.”

In 1847, the Indian Affairs department recommended constructing two new manual labour schools at Alderville and Munceytown. Alnwick (in Alderville) was finished in 1848, and Mount Elgin (in Munceytown) in 1851. These schools were, according to anthropologist Hope MacLean, the result of earlier lobbying by Ojibwa leaders and Methodist missionaries; attendance was voluntary. Ryerson’s influence was evident at both schools. Several teachers had professional training at the new Normal School in Toronto (which opened 1847), and the curriculum offered both academic and practical education. The academic curriculum was similar to the common school curriculum. Students were expected to study and work long hours, with less than one hour a day for recreation. As Ryerson suggested, the Indian Department promised grants for graduates, although they were never provided. By 1860, however, it was clear to all parties that the schools weren’t working, and Ojibwa parents and chiefs had largely withdrawn their support. Alnwick closed in 1859, and Mount Elgin closed in 1863 (although it later reopened).

Ryerson’s 1847 report influenced the development of boarding (or residential) schools for Indigenous students, although he was not personally involved in their implementation; he also died before the residential school system began to take shape in the Canadian West in the 1880s.

Legacy

Ryerson left his mark on many cultural institutions. In 1829, he founded the Methodist Book Room, which later became Ryerson Press and was sold to American publisher McGraw-Hill in 1970. The Normal School buildings at St. James Square in Toronto housed not only the training program for teachers but also the Department of Education and cultural displays for the public. These were early prototypes for the many publicly supported museums and galleries that exist across Ontario today. This included the Museum of Natural History and Fine Arts (established 1857), Canada’s first publicly funded museum. It started its collection through Ryerson’s trips to Europe in the 1850s. After Confederation, it became the Ontario Provincial Museum and later the Royal Ontario Museum. The St. James buildings also included an arboretum and agricultural college; it led to the development of the Ontario Agricultural College at the University of Guelph. The art school established on the property later became the Ontario College of Art and Design University.

Many educational institutions were named in Ryerson’s honour, including Ryerson University, which opened as the Ryerson Institute of Technology in 1948. Since 2021, however, several schools have been renamed due to controversy over Ryerson’s role in the development of residential schools and his involvement in the wider attempt to assimilate Indigenous peoples into Canadian society. This includes Ryerson University, which became Toronto Metropolitan University in 2022. Activists also vandalized a statue of Ryerson at the university in 2020 and 2021; on 6 June 2021, it was toppled and decapitated by protestors.

There is ongoing debate about Ryerson’s responsibility for the residential school system. Neither the Truth and Reconciliation Commission nor its chair, Murray Sinclair, blamed Ryerson for residential schools. Ryerson did not recommend forcing Indigenous children to attend “industrial schools”, nor did he suggest punishing students for speaking Indigenous languages. Yet many activists, both within and outside academia, have denounced Ryerson for his influence on the development of the residential school system, which they consider a form of genocide. The controversy about Ryerson is part of a wider debate about decolonization that is being argued on university campuses and in the public sphere. It also reflects a shift toward social activism in university faculties, including history departments. Other historians and public intellectuals have countered that reviews of Ryerson’s legacy should assess his attitudes and contributions to education, residential schools and Indigenous relations in their historical context.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom