Founding, 1713

In the 17th and 18th centuries, France and Britain competed both for territorial control of Atlantic Canada and for the valuable cod fisheries off its coasts. In the Treaty of Utrecht (1713), Britain won control of French territories in Newfoundland and Acadia (mainland Nova Scotia). That year the French colonized Île Royale (Cape Breton Island) and founded Louisbourg. Work on the fortifications began in 1719. Strategically located on the northeast tip of Île Royale, at the entrance to the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Louisbourg was designed to guard the gateway to New France.

The fortress, which took more than 24 years to build, was constructed by military engineers under Jean-François Verville, and later Étienne Verrier, based on designs by Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban, the chief engineer of French king Louis XIV. Its walls were nearly 11 meters thick in some places, rose nine metres above a deep ditch, and were faced by the sea on three sides. They had emplacements for 148 cannon, though the full complement of guns was never installed. Additional gun emplacements around Louisbourg harbour and on Battery Island further protected the seaward approach to the town. The ground on the landward side of Louisbourg was considered to be too marshy to allow an attacking enemy to deploy heavy artillery within range of the walls. Louisbourg was thought to be impregnable.

The construction and maintenance of the fortress was expensive. King Louis XV was said to have remarked that he expected to see its walls rising above the horizon when he looked out a window of his palace at Versailles, in France. Because of Louisbourg’s remote location and inhospitable climate, governors and military officers disliked being posted there. Drunkenness among common soldiers was a constant problem.

Growth

In addition to its military purpose, Louisbourg became a substantial town and seaport. Little agriculture was carried out there, the cod fishery being the principal economic activity. As a base for the fishing industry, Louisbourg developed diversified shipping links. Each year the port welcomed trading vessels from France, the Caribbean, the British American colonies, Acadia and Québec. Fishermen from France and Spain — Breton, Norman and Basque — joined the fishing industry each summer. The town's settler population, drawn partly from New France and from France itself, grew to roughly 2,000 by 1740 and double that in the 1750s. It's believed that around 381 enslaved people lived in Louisbourg during the 18th century. (See also Black Enslavement in Canada; Enslavement of Indigenous People in Canada.)

Although its governor was subservient to the governor general of New France at Québec, Île Royale functioned as a separate colony. With its military garrison and its importance as a fishing and trading port, it was the centre of French power in the region.

First Siege, 1745

In 1744, Britain was drawn into conflict with France as part of the larger War of the Austrian Succession. The Anglo-French clash would be known in the British colonies as King George’s War. Until this time, Louisbourg had not participated in any military actions, although the fortress had provided refuge for Indigenous people allied with the French who raided English settlements. Louisbourg also offered a safe harbour for French privateers who preyed on fishing fleets and ships from New England.

On 24 May 1744, a force of soldiers from Louisbourg aboard a fleet of 17 vessels, under the command of Captain François du Pont Duvivier, made a surprise attack on the small English fort and settlement at Grassy Island, near Canso (on the present-day Nova Scotia mainland), forcing the British garrison there to surrender. The French destroyed the settlement and took the British to Louisbourg as prisoners. While the British awaited transfer to Boston in a prisoner exchange, their officers were free to move about the town. They took note of weaknesses in the so-called “impregnable” fortress.

In Boston, the freed officers reported their observations to Massachusetts governor William Shirley. They told him that Louisbourg’s garrison was undermanned, and that morale among the French troops was low, largely because of poor food and because they hadn’t been paid in months. They also said that due to poor construction, parts of the seemingly formidable walls were crumbling. They also revealed the presence of nearby ridges and hills overlooking Louisbourg’s landward walls. And they made sketches of Louisbourg’s defences, which they gave to Shirley.

Shirley raised a force of more than 4,000 New Englanders, commanded by William Pepperell, for an expedition against Louisbourg. The colonial army would be supported by a Royal Navy squadron under Commodore Peter Warren. In April 1745, Pepperell established a base at Canso, where he met with Warren in early May to plan a land and sea operation.

The first siege of Louisbourg began on 11 May 1745. Pepperell had captured strategic points near the fortress, and Warren’s ships blockaded the harbour. The colonial army used sledges to haul artillery across marshy ground to high points from which the guns could bombard the town and batter the walls. The French warship Vigilant carrying vital supplies and reinforcements, was captured by Warren’s squadron. By 28 June, Louisbourg’s walls had been breached and Warren’s fleet was poised to enter the harbour. Short of supplies and ammunition, and under pressure from the town’s merchants to capitulate, French governor Louis DuPont Duchambon surrendered.

Arrangements were made for most of the population to be transported to France. Warren was promoted to rear admiral, and Pepperell was rewarded by Britain with a baronetcy.

Returned to France, 1748

Under the terms of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle of 1748, the British returned Louisbourg, and all of Île Royale, to the French, much to the disgust of the New Englanders, who considered it an act of betrayal by the British government.

The new French governor, Augustine de Boschenry de Drucour, strengthened Louisbourg’s defences and increased the garrison to more than 3,500 regular troops augmented by militia, marines and sailors. He stocked the storehouses with enough provisions and munitions to last a year in the event of another siege. That came in 1758 during the Seven Years War (1756–63), known in the American colonies as the French and Indian War.

Britain’s ultimate objective in North America during the 1750s was the capture of the French stronghold of Québec. Before an invasion force could be sent up the St. Lawrence River, however, Louisbourg — guarding the entrance to the Gulf of St. Lawrence — would have to be taken again.

Second Siege, 1758

A British fleet appeared off Louisbourg in early June 1758. In command were Major-General Jeffery Amherst and Admiral Edward Boscawen. One of the senior officers was Brigadier-General James Wolfe.

The second siege of Louisbourg began on 8 June when Wolfe led troops ashore at Gabarus Bay, south of Louisbourg. From that base, he successfully drove French defenders from several strategic positions around the harbour, including Lighthouse Point. By 25 June, his artillery had knocked the French guns on Battery Island out of action, and his siege was drawing nearer to Louisbourg’s walls. In one of the many skirmishes and raids that took place during the siege, Wolfe captured the high ground overlooking the fortress's Dauphin Gate. That enabled the British to move in their biggest guns, 24 and 32 pounders, to fire on the town and on the five French warships that were anchored as close to the walls as possible.

The French returned fire, but as the days passed, most of their cannon were disabled. On 21 July, a British mortar shell exploded in the magazine — the ammunition storeroom — of a French ship, causing a fire that spread to two other vessels, burning all three to the waterline. On 26 July, a British Royal Navy raiding party attacked the two remaining French warships. They set one on fire, and sailed the other one away to join the British fleet.

Realizing that he could not hold out any longer, Drucour surrendered the same day. The town’s civilians would be allowed to return to France, but soldiers and officers would be sent to England as prisoners of war. To ensure that Louisbourg would never again pose a threat — should a treaty once more return it to the French — British engineers completely destroyed the fortress.

The fall of Louisbourg, followed by the capture of Québec in 1759 and the capture of Montréal in 1760, ended France's military and colonial power in what is now Canada. Former French territories became part of British North America. The small islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon, off the coast of Newfoundland, were acquired by France in 1763 — replacing Île Royale as a French base for the fishing industry.

Louisbourg Today

The modern town of Louisbourg, Nova Scotia, a small fishing port, grew up at the opposite end of Louisbourg harbour from where the fortress had stood.

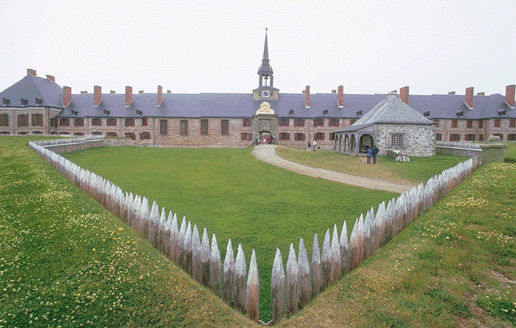

The Fortress of Louisbourg was named a national historic site in 1928. In 1961, Parks Canada began a reconstruction of the fort based on a comprehensive archaeological investigation, and examination of the colony's well-preserved historical records. Part of the fortifications, the citadel buildings, the town quay and several streets with their homes, shops and taverns are now rebuilt in intricate detail, resembling what would have stood there around the year 1744.

The fortress is open to the public year-round, and is interpreted for visitors by guides, costumed animators and museum displays. The reconstruction is a major visitor attraction, an important contributor to Cape Breton's tourist economy and a world-class model of historic-site reconstruction.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom