The National Energy Program (NEP) was an energy policy of the government of Canada from 1980 through 1985. Its goal was to ensure that Canada could supply its own oil and gas needs by 1990. The NEP was initially popular with consumers and as a symbol of Canadian economic nationalism. However, private industry and some provincial governments opposed it.

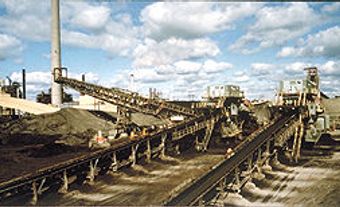

A federal-provincial deal resolved controversial parts of the NEP in 1981. Starting the next year, however, the program was dismantled in phases. Global economic conditions had changed such that the NEP was no longer considered necessary or useful. The development of the oil sands and offshore drilling, as well as the rise in Western alienation and the development of the modern Conservative Party of Canada, are all aspects of the NEP’s complicated legacy.

Key Terms

Protectionism The practice of protecting the industries of a country by restricting foreign competition in their home market. (See Protectionism.)

Price controls Restrictions that a government sets on the price of specific goods. Price controls are usually a short-term measure to control the affordability of the goods.

Background

The federal government had been involved in regulating and developing the Canadian oil and gas industry since the early 1960s. From 1961 to 1973, the government maintained a protected market for Western Canadian oil to help the industry grow. Two major oil crises in the 1970s encouraged the federal government to secure oil resources for Canadian consumers by taking a more active role in developing the Canadian oil and gas sector. (See Oil and Gas Policy in Canada, 1947–80.) The National Energy Program was the policy guiding this role.

Objectives

The National Energy Program (NEP) had three main objectives:

- Increase Canadian participation in the oil and gas sector

- Establish fair energy pricing for Canadian consumers

- Secure Canada’s supply of oil and gas

Accomplishing these goals would make Canada energy-independent. The nation would no longer depend on foreign oil imports nor be affected by changes in the world price of oil. The NEP would guarantee Canadian consumers access to made-in-Canada oil and gas at set prices. It was also designed to increase revenue for the federal government.

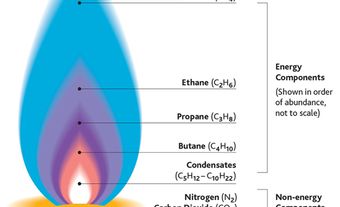

To accomplish these goals, the NEP required much more federal government involvement in the energy sector. The government would encourage exploration and provide new funding for research and development. New taxes and price controls were introduced. The NEP encouraged greater local participation in the oil industry. It also aimed to conserve oil by helping consumers switch from oil to natural gas and electricity for home heating.

This kind of economic nationalism and direct intervention in the economy was not new in Canada. The country had developed Crown corporations to play a variety of economic and policy roles earlier in the 20th century. Crown corporations had grown in number during the Second World War. And while Canada’s economy had become less centrally controlled after the Second World War, the government remained involved in certain industries throughout much of the Cold War. These industries included a national railway and airline, in addition to aerospace manufacturers, telecommunications networks, nuclear power generation and uranium mining, among many others.

Opposition

The NEP was controversial for several reasons.

First, natural resources such as oil and gas traditionally fell to the provinces. Premiers such as Peter Lougheed of Alberta thought such a major change in Canada’s energy policy should have involved provincial consultation. He and others feared the provinces would lose an important source of revenue.

Complicating this situation was the fact that federal-provincial relations were being tested in the early 1980s. Quebec held a referendum on sovereignty just five months before the NEP was introduced (see Quebec Referendum (1980)).

Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau promised constitutional negotiations between

the provinces and the federal government to develop a new made-in-Canada constitution and

charter of rights. Negotiations over the constitution and the NEP dominated Canadian politics throughout 1981. Trudeau pushed for a strong federal government

and a program of nation-building projects and policies. Meanwhile, premiers (including Lougheed and Quebec’s René Lévesque) wanted a looser association where the provinces

had greater control over their own affairs.

A second source of controversy was the NEP’s price controls. Though price fairness benefited all Canadian consumers, it also limited the profits of private industry and the royalties paid to oil-producing provinces.

Finally, the NEP was based on the idea that access to cheap oil and gas was more of a public need than a free-market commodity. While the free market is driven by the quest for profit, the NEP was driven by the need to keep consumer costs as low as possible. These interests tend to be at odds with one another.

Dismantling

Like the other energy policies that had come before it, the NEP was subject to provincial-federal negotiations. The federal government and the governments of the oil-producing provinces agreed to an amended version of the NEP in 1981. The compromise involved the federal government agreeing to modify price controls and regulations. In turn, the provinces agreed that the federal government had a right to special taxes designed to increase federal revenue and Canadian energy independence.

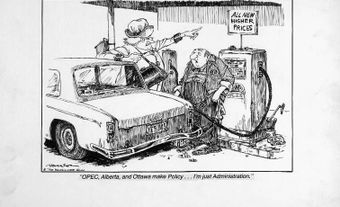

Cartoon by Len Norris for the 1 September 1981 edition of the Vancouver Sun.

As the global price of oil declined from 1983 to 1985, federal and provincial governments continued to negotiate changes to the NEP to help private industry. By 1984–85, the economic conditions that had led to the creation of NEP no longer existed. Prime Minister Brian Mulroney proposed a new energy policy during his first term in office. The new policy aimed to address the important changes in the global oil market. The Western Accord on Energy went into effect on 1 June 1985, ending the NEP and more than 20 years of federal government protectionism and regulation of the oil and gas industry.

Legacy

By the time the program was implemented in the 1980s, some of the economic factors that had led to the creation of NEP no longer applied. Global economic and political trends had shifted in favour of deregulation, privatization and limited government intervention in the economy. (See also Economic Regulation.) The NEP’s fate reflects Canada’s participation in these growing international trends. The modern Conservative Party of Canada and contemporary Western alienation can, in part, be traced back to significant public opposition to the NEP in Western Canada.Though it failed at its main goal of national energy security, the NEP played a key role in the development of Canada’s modern energy industry. The NEP was heavily invested in the development of oil sands in Western Canada and in offshore drilling in the Atlantic provinces.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom