The North-West Resistance (or North-West Rebellion) was a violent, five-month insurgency against the Canadian government, fought mainly by Métis and their First Nations allies in what is now Saskatchewan and Alberta. It was caused by rising fear and insecurity among the Métis and First Nations peoples as well as the white settlers of the rapidly changing West. A series of battles and other outbreaks of violence in 1885 left hundreds of people dead, but the resisters were eventually defeated by federal troops. The result was the permanent enforcement of Canadian law in the West, the subjugation of Plains Indigenous Peoples in Canada, and the conviction and hanging of Louis Riel.

Disaffected Peoples

By the late 1870s, the Plains Indigenous nations of the West — the Cree, Siksika, Kainai, Piikani, and Saulteaux — were facing disaster. The great bison herds had disappeared, pushing people to near starvation. Much of their land had also been signed away in treaties, and they were now seeing towns, farm fences and railways appearing on the once expansive prairies. In 1880, Cree chief Mistahimaskwa (Big Bear), and Isapo-muxika (Crowfoot), leading chief of the Siksika, founded a confederacy to try to solve their people’s grievances.

Meanwhile the Métis people — still feeling vulnerable after their Red River uprising in Manitoba a decade earlier — had grievances of their own. Their old life as fur traders and carriers for the Hudson’s Bay Company was disappearing, along with the bison on which they too depended. They were also waiting, without much help from the distant federal government, for reassurance that title to their river-lot homesteads and farms would be guaranteed.

White settlers in Saskatchewan who had purchased land expecting that the Canadian Pacific Railway line would run northwest from Winnipeg to Edmonton, learned suddenly in 1882 that the CPR would go farther south, through Regina and Calgary. Poor harvests in 1883 and 1884 added to their problems, along with an unsympathetic Dominion government back East.

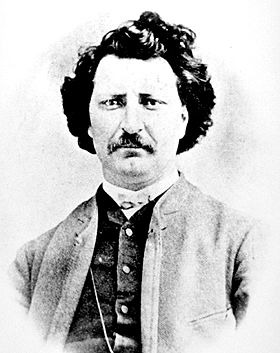

Louis Riel Returns

In the summer of 1884, the Métis of Saskatchewan brought Louis Riel, the Red River Resistance leader, back to Canada from exile in the United States. Riel urged all dissatisfied people in the North-West to unite and press their case on Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald’s Conservative government, which had failed to address their grievances.

In the fall of 1884, Riel prepared a petition and urged Métis and non-Métis settlers alike to sign it. On 8 March 1885 the Métis passed a 10-point “Revolutionary Bill of Rights” asserting Métis rights of possession to their farms, and made other demands, including: “That the Land Department of the Dominion Government be administered as far as practicable from Winnipeg, so that the settlers may not be compelled as heretofore to go to Ottawa for the settlement of questions in dispute between them and the land commissioner.”

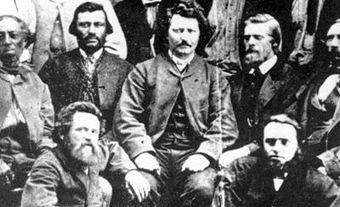

On 18 and 19 March, an armed force of Métis formed a provisional government, seized the parish church at Batoche, and demanded the surrender of the nearby Hudson’s Bay Company post at Fort Carlton. Riel was named president of the provisional government, and famed Métis hunter and tactician Gabriel Dumont was installed as military commander.

Battle at Duck Lake

In anticipation of police intervention of some kind — but without knowing that federal troops were coming by rail from the East — the Métis occupied the community of Duck Lake, midway between Batoche and Fort Carlton. On the morning of 26 March 1885, a force of about 100 North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) and armed citizen volunteers, moved towards Duck Lake under the command of Superintendent Lief Crozier.

A large group of Métis and First Nations met them on the Carlton Trail outside the village. Negotiations ended in confusion and the police and volunteers fired at their enemy hidden in a hollow north of the road, and in a cabin to the south. The battle ended shortly after, with the police and volunteers retreating to Fort Carlton. Nine volunteers and three police members were killed, with many more injured. Five Métis and one First Nations warrior died. Riel persuaded his men not to pursue the retreating force, and the Métis returned to Batoche. The police evacuated Fort Carlton and retired to Prince Albert.

Canada Mobilizes Troops

In Ottawa, the government’s reaction was swift and clear. There were only a few hundred full-time soldiers in Canada, but militia mobilization began on 25 March 1885, the day before the Battle of Duck Lake. CPR manager William Van Horne quickly arranged for Canadian troops to be transported across the unfinished gaps in the new railway, enabling them to reach Qu’Appelle, Saskatchewan, by 10 April. In less than a month, almost 3,000 troops had been transported west; most were militia units from Ontario but the force included two Quebec battalions and one from Nova Scotia. From the West came about 1,700 of the eventual total of just over 5,000 troops that Major-General Frederick Middleton would command.

Resistance Increases

The victory at Duck Lake encouraged a large contingent of Cree to move on Battleford from reserves to the west. Residents of the area flocked to the safety of Fort Battleford. On 30 March, Assiniboines south of Battleford killed two settlers and joined the Cree forces. Terrified settlers huddled in Fort Battleford for almost a month as the Cree and Assiniboine organized a huge war camp to the west.

Big Bear had been the last Plains chief to sign a treaty with Ottawa, and in 1885 he was still resisting moving his people onto a reserve, still agitating for a better deal. As a result, his band included some of the more militant Plains Cree. The government took a hard line with Big Bear’s band, cutting off rations to force them to settle. By the spring of 1885, it was almost inevitable that Big Bear’s band at Frog Lake, north of modern-day Lloydminster, would clash violently with the government.

On the night of 1 April, warriors of Big Bear’s band took several Métis and non-Métis settlers prisoner. On Thursday 2 April, war chief Wandering Spirit shot and killed federal Indian agent Thomas Quinn. Chief Big Bear then tried to stop the violence, but the warriors took their own initiative from their war chief and killed two priests, the government farming instructor, an independent trader, a miller and three other men. Several people were spared, including the widows of two of the dead men.

Battle of Fish Creek

General Middleton’s original plan was simple. He wanted to march all his troops north from the railhead at Qu’Appelle to Batoche. But the killings at Frog Lake and the “siege” of Battleford forced him to send a large group under Lieutenant-Colonel William Otter north from a second railhead at Swift Current to relieve Battleford. Pressure from Northwest Territories officials in present-day Alberta led to the creation of a third column at Calgary under Major-General Thomas Bland Strange.

Middleton set off on the 50 km march to Batoche from Clarke’s Crossing on the South Saskatchewan River on 23 April. About 900 men, including two artillery batteries, were split into two groups, one for each side of the river. The Métis were determined to fight, but differed about where to make a stand. Louis Riel wanted to concentrate all efforts on defending Batoche; Gabriel Dumont favoured a more forward position. Dumont won the argument and on 12 April, with about 150 Métis and First Nations supporters, prepared an ambush at Tourond’s Coulee, which the government soldiers would know as Fish Creek, 20 km south of Batoche on the east side of the South Saskatchewan River.

As Middleton’s scouts approached the coulee early on 24 April, the resistors opened fire. Until mid-afternoon, Middleton’s soldiers tried unsuccessfully to drive Dumont’s men from the ravine and suffered heavy casualties, with six killed and 49 wounded. The resistors had only four killed. It took most of the day for Middleton to get the troops from the west bank across the river on a makeshift ferry and they arrived too late to take part in the fighting. At the end of the day, both commanders decided to pull back. The Métis had held their ground and Middleton’s advance was stopped.

On 1 May, Colonel Otter moved west from Battleford with 300 men and early the next day confronted the Cree and Assiniboine force just west of Cut Knife Creek, 40 km from Battleford (see Battle of Cut Knife). The Indigenous force had enormous advantages of terrain, virtually surrounding Otter’s troops on an inclined, triangular plain. Cree war chief Fine Day deployed his soldiers successfully in wooded ravines. After about six hours of fighting, Otter retreated. Casualties would have been very high as the militia re-crossed the creek, had not Chief Poundmaker persuaded the Indigenous warriors not to pursue the government troops. Eight of Otter’s force died; five or six Indigenous people were killed.

Battle of Batoche

Otter’s setback prompted General Middleton to wait two weeks for reinforcements before resuming his march toward Batoche. On the morning of 9 May, his forces attacked the carefully constructed defences at the southern end of the Batoche settlement. The steamer Northcote, transformed into a gunboat, attempted to attack the village from the river, but the Métis lowered the ferry cable, incapacitating the boat. After a brief, intense conflict in the morning, the cautious Middleton kept the attackers at a discreet distance from the enemy positions. In the afternoon, after failing to make headway against the entrenched enemy, the troops built a fortified camp just south of Batoche.

The next two days were repeats of the first. The troops marched out in the morning, attacked the Métis lines with little success and retired to their camp at night. On 12 May Middleton tried a co-ordinated action from the east and south but the southern group failed to hear a signal gun and did not attack. In the afternoon, apparently without specific orders, two impetuous colonels led several militia units in a charge. The resistors, weary and short of ammunition, were overrun.

Eight of Middleton’s force died during the Battle of Batoche. The general later reported that 51 Métis and First Nations were killed, but that number has often been disputed. Louis Riel surrendered on 15 May; Gabriel Dumont fled to Montana.

Final Shots

During the Battle of Batoche, General Strange was resting his Alberta Field Force at Edmonton after a hard march from Calgary. The column left Edmonton on 14 May and on 28 May they caught up to the Frog Lake Cree, dug in at the top of a steep hill near a prominent landmark known as Frenchman’s Butte, 18 km northwest of Fort Pitt (see Battle of Frenchman’s Butte). Direct advance against the entrenched Indigenous warriors would have been very difficult, and Strange’s scouts found no practical way around the Cree positions. They fired at each other from long range for several hours before both sides retreated.

The last shots of the resistance were fired on 3 June at Loon Lake, 40 km north of Frenchman’s Butte, where a few men under North-West Mounted Policeman Sam Steele skirmished with the retreating Frog Lake Cree. None of Steele’s men were killed but four Indigenous warriors died, including a prominent Woods Cree chief (see Battle of Steele Narrows).

Chief Pitikwahanapiwiyin (Poundmaker) and a number of Battleford area bands had surrendered to General Middleton on 26 May at Battleford. At the end of May, Big Bear was the only important leader still at large. General Middleton’s pursuit of Big Bear was so cumbersome that the soldiers never did find him. The Frog Lake Cree released their prisoners on 21 June, and Big Bear surrendered to the Mounted Police on 2 July at Fort Carlton. Before the first of August, almost all the militia were home.

Arrest and Prosecution

The North-West Resistance had not been a concerted effort by all groups in the North-West. Even most Métis communities stayed out of the fighting. The people of the South Branch communities of the Saskatchewan River valley, centered at Batoche, had been the principal combatants. The Plains Cree of Big Bear’s band had participated, but the neighbouring Woods Cree had not. Some Cree from the Batoche area fought with the Métis, as did Dakota warriors from a reserve from south of present-day Saskatoon. The Siksika had remained neutral, the Kainai refusing to abandon their traditional animosity towards the Cree. Meanwhile, almost every settler had rallied to the government cause, even though their vocal anti-government agitation before the shooting started had helped to create the environment that made the resistance possible.

As the government soldiers left the West, Louis Riel’s trial for high treason began at Regina. Riel demanded a political trial. His lawyers failed in their attempt to convince the jury that Riel’s religious and political delusions made him unaware of the nature of his acts — largely because Riel was so eloquent in his address to the jury on 31 July. The law provided no alternative to the death penalty, and on 18 September Riel was sentenced to be hanged (see Capital Punishment).

The government arrested many people on the lesser charge of treason-felony. W.H. Jackson, Riel’s personal secretary, was acquitted by reason of insanity. Most of the provisional government council pleaded guilty and received sentences ranging from conditional discharges to seven years in prison. Chiefs Poundmaker and Big Bear were tried and sentenced to three years in jail. Several other Indigenous peoples from Batoche, Frog Lake and Battleford were sentenced to various terms after treason-felony convictions. Dakota chief White Cap was the only major Indigenous political leader acquitted of treason-felony. Eleven Indigenous warriors were convicted of murder.

Hanging of Louis Riel

Louis Riel’s execution was postponed three times: twice to allow appeals to higher courts, then for a fuller medical examination of his alleged insanity. The appeals failed and the medical commission report was ambiguous. The federal government could have commuted the death sentence, but the decision to let the law take its course was purely political. Riel was hanged at Regina on 16 November 1885.

French Canadians had supported the campaign to colonize the West, but there was widespread outrage in Québec over Riel’s execution. Wilfrid Laurier’s passionate denunciation of the government’s action was a major step forward in his political career (see Wilfrid Laurier: Speech in Defence of Louis Riel, 1874).

On 27 November, six Cree and two Assiniboine warriors, including Frog Lake war chief Wandering Spirit, were hanged at Battleford. Three other convicted murderers had their sentences commuted. All the resistors sentenced to jail were released early. Gabriel Dumont, among others, eventually returned from the US under the terms of a general amnesty.

The resistance had profound effects on Western Canada. It was the climax of the federal government’s efforts to control the Indigenous communities as well as the settler population of the West. Indigenous peoples who had thought themselves oppressed after the treaties of the 1870s became subjugated and administered people. The most vocal members of the Métis leadership had either fled to Montana or were in jail. It took the Indigenous peoples and communities of Western Canada many decades to recover politically and emotionally from the defeat of 1885.

Resistance or Rebellion?

The Red River and North-West Rebellions are known by many names, including the “Riel Rebellions,” the “Manitoba Rebellion” and the “Saskatchewan Rebellion.” They are also known as the “Red River Resistance,” the “1885 Resistance” and the “Northwest Resistance.” The terms rebellion and resistance are synonyms, but depending on which one is used, the perspective from which historical events are understood changes.

According to the Canadian Oxford Dictionary, for example, rebellion is defined as an “organized and armed resistance to an established government,” while resistance means “resisting authority, especially in an occupied country.”

Indigenous studies scholars and many historians refer to the Métis and First Nations uprisings as resistances, meaning reactions against European colonization. This is because Métis and First Nations self-governed the land long before Rupert’s Land was transferred to the Dominion of Canada.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom