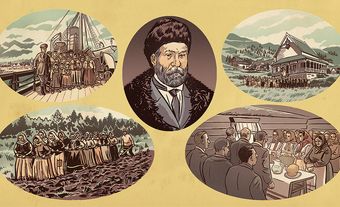

Peter Vasilevich Verigin, Doukhobor leader (born 1859 in Slavianka, Russia; died October 1924 near Grand Forks, British Columbia). Exiled in Russia, Verigin immigrated to Canada in 1902. There, he became a powerful and controversial Doukhobor leader in Western Canada. Verigin died when the train in which he was travelling exploded, leading some to believe he was assassinated.

Early Life in Russia

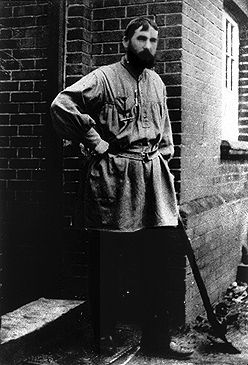

Verigin was born the eighth of nine children. His family was economically secure and, unlike many others in his community, he received an elementary education. Verigin’s maternal great-grandfather, Savelii Kapustin, had been an early 19th century Doukhobor leader. The Doukhobors were a group of Russian Christians who insisted that the priests, symbols and rules of the Church were unnecessary because God lives in each person. Hymns, psalms and stories they called the Living Book were the foundation of an oral understanding of their beliefs. The Russian government considered their rejection of external rules and leaders as dangerous and so, beginning in the late 1700s, persecuted the Doukhobors.

From 1864 to 1866, the Doukhobors were led by Verigin’s relative, Luker’ia Kalmykova who recognized his leadership potential. She ordered him to divorce his wife, who was pregnant with their first child, and to become her personal secretary. Upon Kalmykova’s death in 1866, the majority of the Doukhobors wanted Verigin to become the new leader. Others hoping to succeed her convinced tsarist officials that he was a threat to the Russian government, which led to his arrest. In 1887, he was sent into exile in remote northern Russia.

Despite efforts by Russian officials to cut off Verigin’s contact with the Doukhobor community, he snuck instructions to his loyal followers. In 1893 he issued a manifesto stating that they must rid themselves of personal property, live communal lives, and become vegetarians. Verigin later also instructed them to destroy their weapons, reject all forms of violence, and never do military service. In the summer of 1895, his followers obeyed his instructions to gather and burn their weapons to publicly demonstrate their pacifism.

Influential Russian writer and social reformer Leo Tolstoy was among Verigin’s correspondents and an active supporter of Doukhobor beliefs and actions. Tolstoy’s letters and articles brought international attention to Doukhobor persecution. Among those he wrote to was the University of Toronto’s Professor James Mavor. Mavor passed the information to Canada’s minister of the interior, Clifford Sifton, who, at that time, was leading an ambitious effort to attract settlers to Canada’s west. Sifton’s immigration policies, along with Tolstoy’s financial help, led to about 7,500 Doukhobors coming to Canada in 1899.

Verigin was initially opposed to immigration to Canada, but when he was released from exile in July 1902, he joined the exodus, arriving in Winnipeg in December of that year. (See also Russian Canadians.)

Verigin in Canada

Verigin was welcomed by Doukhobors in Canada as their spiritual leader. Many referred to him as Gospodnii, or Lordly, meaning “belonging to the Lord.” At first, Doukhobor land in Canada was held collectively, in keeping with their religious principals. However, Verigin encouraged men to find work away from the community. He created a small town in southern Saskatchewan that would serve as the Doukhobor administrative centre and called it Veregin. With these actions, 57 Doukhobor communities were established. His tagline and guiding principle was, “Toil and peaceful life.”

Many Canadians grew to resent the Doukhobors for living in insular communities where group purchasing and shared labour afforded advantages over those trying to make it on their own. The governments of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta at various times enacted discriminatory measures, including not recognizing Doukhobor marriages or deaths or their right to vote.

In 1905, the federal government withdrew the exemption which had allowed the Doukhobors to own land collectively. Further, to register land, an owner had to swear an oath to the crown which could entail military service in war time. The government’s decision split the Doukhobors. Some, including Verigin, insisted that individual land ownership, an oath to a secular power, and military service violated the Doukhobor’s foundational principles. Others that became known as Independents, however, registered their land and either swore the oath or claimed conscientious objector status.

Verigin went to Moscow in 1906 to explore the possibility of a return to Russia. He was told that they would not be exempt from military service. Upon his return to Canada, Verigin found that the federal government had revoked the titles to over half of the lands collectively held by the Doukhobors, and seized much of the remainder.

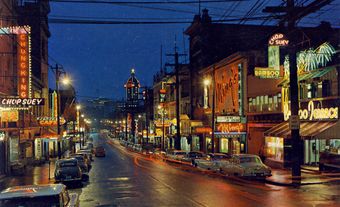

Verigin found land in an isolated portion of the Kootenay district of British Columbia which could be purchased without having to swear an oath to the federal government. In 1907, about 20 per cent of Doukhobors, mostly Independents, remained on the prairies. The rest, the Christian Community of Universal Brotherhood, followed Verigin to begin again in British Columbia.

New, self-sustaining communities were established. Conflicts soon arose within the communities as some orthodox Doukhobors became uncomfortable with what they perceived as growing materialism and modernism among other Doukhobors. Others, however, argued that they could adopt some modern ways while remaining faithful to their beliefs. Meanwhile, Verigin negotiated with federal and provincial authorities. He agreed, for example, to obey a provincial law regarding sending children to public schools if there was no religion taught and if adults would be exempt from military service.

Verigin’s Death

On 29 October 1924, the 65-year-old Verigin was aboard a train travelling between the town of Brilliant and the Doukhobor community at Grand Forks. Outside Farron, an explosion ripped the train apart. Verigin and all but two of his fellow travellers were killed instantly. The RCMP investigated the explosion but could not determine if it was an accident or assassination. His death led to great speculation. (See Mysteries in Canadian History.)

Some believed that Verigin’s son, Peter Petrovich, had been behind the explosion. He had visited Canada before, and while there, his relationship with his father was strained. In 1927, Petrovich returned from Russia to become a Doukhobor leader in British Columbia. Others believed one of the competing factions within the Doukhobor community had killed Verigin. Under particular suspicion was a faction called the Sons of Freedom, a splinter group who believed that Verigin and other Doukhobors had become too materialistic. Many Doukhobors believed, and some still believe, that the Canadian government might have been behind the death of their leader. Some even suspected it was Americans who feared that Verigin was considering moving his followers to the United States. The case remains unsolved.

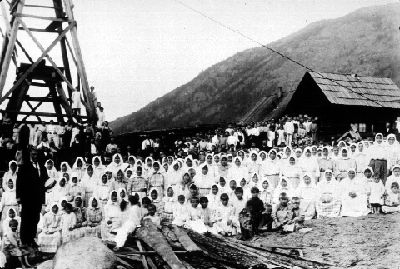

Thousands attended Verigin’s funeral near his home in Brilliant, British Columbia on 2 November 1924.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom