Racism is a belief that humans can be divided into a hierarchy of power on the basis of their differences in race and ethnicity. With some groups seen as superior to others on the sole basis of their racial or ethnic characteristics. Racism is frequently expressed through prejudice and discrimination. The belief can manifest itself through individuals, but also through societies and institutions.

Early Racism

While xenophobia — or fear of those unlike us — has long been a part of human cultures, the concept of race first appeared in the English language around the 17th century. North Americans began to use the term in their scientific writings by the late 18th century. Racism began to be studied by scientists in the 19th century. Racism was used to in an attempt to explain political and economic conflicts as well as to justify European colonialism and imperialism across the world.

By the mid-19th century, many racists believed the world’s population could be divided into a variety of races: groups of people who shared similar physical attributes, such as skin colour and hair texture. This process of race categorization is referred to as racialization and is necessary for the emergence of racism as an ideology.

Core Beliefs

Racism claims the human species can be divided into different biological groups that determine the behaviour, economic, and political success of individuals within that group. This belief views races as natural and fixed subdivisions of the human species, each with its distinct and variable cultural characteristics and capacity for the development of civilizations. Thus, racists believe that biological factors can be used to explain the social and cultural variations of humans. Racism also includes the belief that there is a natural hierarchical ordering of groups of people so that superior races can dominate inferior ones.

Racist thinking presumes that differences among groups are innate and not subject to change. Thus, intelligence, attitudes and beliefs are viewed as not affected by one’s environment or history. The existence of groups at the bottom or top of the social hierarchy is interpreted as the natural outcome of an inferior or superior biological makeup and not the result of social influences. Racists reject social integration because they believe the mixing of groups would result in the degeneration of the superior group.

If biological differences are not easily discernible, racists invent biological differences (for example — size of nose or colour of eyes). Racism does not exist because of the presence of objective, physical differences among humans, but rather the social recognition of and the importance attached to such differences.

Racist ideology is based upon three false assumptions: That biological differences are equal to cultural differences; that biological makeup determines the cultural achievements of a group; and that biological makeup limits the type of culture a group can develop. Research shows these assumptions are wrong and largely based on the untenable position that biology is the single cause for everything. Evidence showing that differences within groups are greater than differences between groups, and that social factors have an impact on behaviour, argue strongly against racist beliefs.

Institutional Racism

In the 1960s, the concept of racism was usually applied to the treatment of individuals and the belief that one individual was racially inferior. The term has since broadened to include institutional racism — describing political, economic and social institutions that operate to the detriment of a specific individual or group. Cultural racism is based on the supposed incompatibility of cultural traditions rather than ideas of innate biological superiority.

Racism can also be reflected in the ways that social institutions operate, by denying groups of people fair and equitable treatment. In this case we talk about structure and power, otherwise known as institutional racism. This includes the power to establish what is normal, necessary and desirable and reinforces superiority or preferences for one group over another.

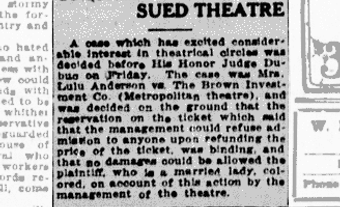

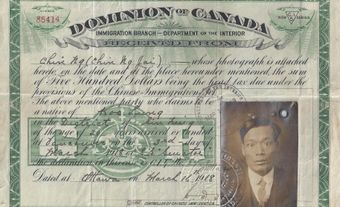

Examples of institutional racism in Canada's history are evident in its restrictive immigration policies and in policies against Indigenous peoples and non-white immigrants, particularly Asians, Black people, and Jews. Institutional racism also exists when policies or programs seem racially neutral, but either intentionally or unintentionally put minority group members at a disadvantage. As an example, in certain provinces the process for selecting citizens for jury duty results in Indigenous people rarely being selected. These dimensions of racism reveal that power, and individuals in positions of power, can create or perpetuate racial policies or practises.

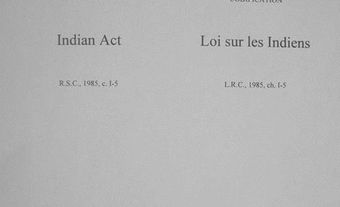

Some of the most intense racist policies have been directed at Indigenous peoples. Until 1960, Indigenous adults could not vote in federal elections unless they first renounced their Indian Act status and gave up treaty rights.

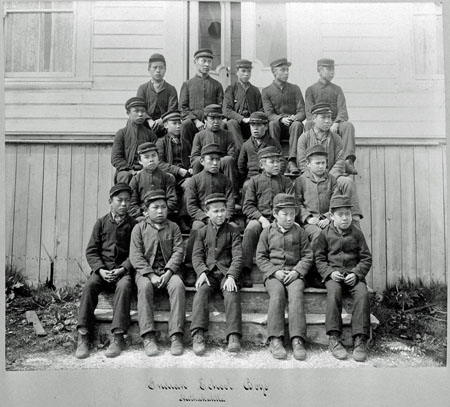

In 1880, the Canadian government began sponsoring residential schools designed to assimilate Indigenous children into Euro-Canadian culture. From the 1930s to the 1990s, institutions across the country were dedicated to assimilating Indigenous children into the dominant culture. Many children were taken from their parents and subjected to humiliating abuse, scientific experiments and poor living conditions. Indigenous culture was routinely insulted, and many students were beaten if they spoke their own language.

Indigenous women are murdered or go missing in Canada at much higher rates than non-Indigenous women — a fact that many believe stems from the impact of racism. Indigenous women account for only 4.3 per cent of Canadian women, but 16 per cent of all homicide victims.

Black Canadians have faced higher scrutiny from police and reports show evidence of racial profiling. One study found that police described 33.6 per cent of drivers stopped in Toronto by police as Black, compared to about 8.1 per cent of the total population being Black.

Fighting Racism

Over the past quarter-century, the provincial and federal governments have implemented laws to combat racism. While blatant racist ideology is uncommon (see Ku Klux Klan), examples of racist beliefs are still evident. Today, racism and discrimination are more commonly experienced by visible minorities.

Canada has federal and provincial laws to protect individuals, groups, and cultural expressions. However, forms of racism and discrimination persist. The Canadian Human Rights Act makes it discriminatory to communicate hatred. The Act protects Canadians from public statements that promote hatred, or incite hate against an identifiable group based on their ethnicity and/or skin colour.

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms specifically addresses the constitutional rights that are necessary in a democratic society, and all Canadian law must be consistent with the Charter. The equality of all Canadians is protected under the Charter. The Charter also protects certain rights guaranteed to Indigenous peoples, and it affirms Canada's multicultural heritage.

The Canadian Human Rights Act prohibits discrimination based on individual characteristics including race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, age, gender, sexual orientation or marital status. The Canadian Multiculturalism Act protects groups from cultural discrimination and is a commitment to new Canadians that they may retain aspects of their culture in Canada. Other key pieces of legislation include the Criminal Code of Canada (which prohibits the promotion of hatred and hate propaganda), and the Employment Equity Act, which protects against discriminatory hiring practices that disadvantage women, Indigenous peoples, individuals with disabilities, and members of visible minorities.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom