The South African War (1899–1902) was Canada's first foreign war. Also known as the Boer War, it was fought between Britain (with help from its colonies and Dominions such as Canada) and the Afrikaner republics of Transvaal and the Orange Free State. Canada sent three contingents to South Africa, while some Canadians also served in British units. In total, more than 7,000 Canadians, including 12 nurses, served in the war. Of these, approximately 270 died. The war was significant because it marked the first time Canadian troops distinguished themselves in battle overseas. At home, it fuelled a sense that Canada could stand apart from the British Empire, and it highlighted the French-English divide over Canada's role in world affairs — two factors that would soon appear again in the First World War.

How It Started

Britain went to war in 1899 as the imperial aggressor against two small, independent Afrikaner (or Boer) republics. The Afrikaners were descendants of Protestant Dutch, French and German refugees who had migrated in the 17th Century to the Cape of Good Hope on the southern tip of Africa. After Britain took control of the Cape in the 19th Century, many Afrikaners — unwilling to submit to British rule — trekked north into the interior, where they established the independent nations of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State. By 1899 the British Empire (then at the height of its power) had two South African colonies, the Cape and Natal, but also wanted control of the neighbouring Boer states. Transvaal was the real prize, home to the richest gold fields on earth.

Britain's pretext for war was the denial of political rights by the Boers to the growing population of foreigners, or Uitlanders as they were known in the Afrikaans language — mostly immigrants from Britain and its colonies — who worked the Transvaal gold mines. The British government rallied public sympathy for the Uitlander cause throughout the Empire, including in Canada where Parliament passed a resolution of Uitlander support. Britain increased pressure on the Boers and moved troops into the region, until finally in October 1899 the Boer governments made a pre-emptive military strike against British forces gathering in nearby Natal.

Canadians Divided

Canadian opinion was sharply divided on the question of sending troops to aid the British. French Canadians led by Henri Bourassa, seeing growing British imperialism as a threat to their own survival, sympathized with the Boers, whereas most English Canadians rallied to the British cause. English Canada was a staunchly British society at the time; Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee had been celebrated in lavish fashion across the country in 1897. Two years later, if the mother country was going to war, most English Canadians were keen to help her. Dozens of English-speaking newspapers took up the patriotic, jingoistic spirit of the time, demanding Canada's participation in the war.

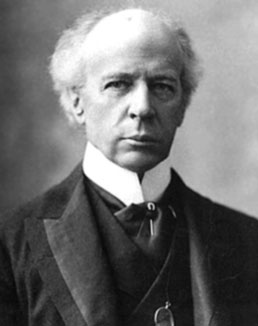

Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier was reluctant to get involved, and his divided Cabinet was thrown into crisis on the matter. Canada did not have a professional army at the time. Eventually, under intense pressure, the government authorized the recruitment of a token force of 1,000 volunteer infantrymen. Although they would fight within the British army, it was the first time Canada would send soldiers overseas wearing Canadian uniforms into battle.

Canadian Contingents

The 1,000 volunteers were organized into the 2nd (Special Service) Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment (RCR). This first contingent was commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel William Otter, a hero of the North-West Rebellion. It sailed on 30 October from Québec — called "the gallant thousand" by the minister of militia, Frederick Borden, whose own son Harold would be killed in South Africa.

As the war continued, Canada had no difficulty raising 6,000 more volunteers, all mounted men. This second contingent included three batteries of field artillery and two regiments — the Royal Canadian Dragoons and the 1st Regiment, Canadian Mounted Rifles. Another 1,000 men — the 3rd Battalion, RCR — were raised to relieve regular British troops garrisoned at Halifax, Nova Scotia. Only the 1st, 2nd and Halifax contingents, plus 12 instructional officers, six chaplains, eight nurses and 22 tradesmen (mostly blacksmiths) were recruited under the authority of the Canadian Militia Act. They were organized, clothed, equipped, transported and partially paid by the Canadian government, at a cost of nearly $3 million.

A 3rd contingent, Strathcona's Horse, was funded entirely by Lord Strathcona (Donald Smith), Canada's wealthy high commissioner to Britain. The other forces to come from Canada — including the South African Constabulary, the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th and 6th Regiments of Canadian Mounted Rifles, and the 10th Canadian Field Hospital — were recruited and paid by Britain. All volunteers agreed to serve for up to one year, except in the Constabulary, which insisted on three years' service.

Canadians also served in British units, and in guerrilla-type army units such as the Canadian Scouts and Brabant's Horse.

Paardeberg

Most of the early Canadian volunteers who sailed for South Africa in October 1899 believed they would be home, victorious, by Christmas. Imperial Britain was the most powerful nation on earth — how could two small Boer republics withstand its military might? By the time the Canadians reached Cape Town in November, however, the British side was in a state of shock. After two months of war the main British forces had either surrendered in fighting, or were besieged by the Boers in garrison towns. Then in December, the British suffered three stunning battlefield defeats in what became known as "Black Week." Suddenly, Britain found itself embroiled in its biggest war in nearly a century.

The setbacks were due not only to British military blunders, but also to the skill of the Boer armies — made up of citizen soldiers who were highly mobile, familiar with the land, equipped with modern weapons, and determined to defend their homeland. In February 1900 the British reinforced and reorganized their war effort. Under new leadership, the British abandoned the slow and vulnerable railway lines, instead marching their armies directly across the African grasslands to the Boer capitals of Bloemfontein and Pretoria.

On 17 February a British column of 15,000 men — including the 1,000 troops of the first Canadian contingent — confronted a Boer force of 5,000 which had circled its wagons at Paardeberg, on a stony plain south of Bloemfontein. For nine days the British besieged the smaller Boer force, pounding them with artillery and trying without success (including one failed, suicidal charge by the Canadians) to assault the Boer encampment with infantry.

On 26 February, the Canadians under William Otter were ordered into the fray again, this time to attempt a night attack. After several hours of desperate fighting, the Boers surrendered to the Canadians just as dawn broke the following morning. It was the first significant British victory of the war, and Canada was suddenly the toast of the empire. Hundreds of men on both sides, including 31 Canadians, died at Paardeberg. Still, the British commander Field Marshal Frederick Roberts heaped praise on Otter and his men. "Canadian," he said, "now stands for bravery, dash and courage."

Leliefontein

By June 1900, Bloemfontein and Pretoria had fallen to the British and Paul Kruger, the Transvaal president, had fled to exile in Europe. But rather than surrender, the remaining Boer forces organized themselves into mounted guerrilla units and melted away into the countryside. For the next two years the Boers waged an insurgency against the British — raiding army columns and storage depots, blowing up rail lines and carrying out hit-and-run attacks. The British responded with a scorched-earth strategy — burning farms and herding tens of thousands of Boer and African families into concentration camps, until the last of the "bitter enders" among the Boer fighters were subdued.

On 7 November 1900, with the guerrilla phase of the war underway, a British force of 1,500 men was attacked at Leliefontein farm in the eastern Transvaal, by a large group of Boers on horseback, intent on capturing the supply wagons, and the guns of the Royal Canadian Artillery, at the rear of the column. For two hours the Canadian artillery crews, and soldiers of the Royal Canadian Dragoons, fought a wild, mounted battle to protect the guns.

Three Canadians died at Leliefontein. Three others, including a wounded Lieutenant Richard Turner (who would later serve as a general in the First World War), won the Victoria Cross for their bravery in saving the guns.

Boschbult

Perhaps the most heroic fighting carried out by Canadians in South Africa occurred near the end of the war, on Easter Monday, 31 March 1902, at the Battle of Boschbult farm — also known as the Battle of Harts River. Another British column of 1,800 men had been patrolling the remote, western corner of the Transvaal when it ran into a surprisingly large enemy force of 2,500 Boers. Outnumbered, the British installed themselves around the farm buildings at Boschbult, set up their defences, and for the rest of the day tried to defend against a series of charges and attacks by mounted enemy soldiers.

On the outer edge of the British defence line, a group of 21 Canadian Mounted Riflemen, led by Lieutenant Bruce Carruthers, fought valiantly against the charging enemy horsemen. Carruthers' men were eventually cut off and surrounded, and many were badly wounded, but they refused to surrender their position until they had fired the last rounds of their ammunition. Eighteen of the 21 were killed or wounded before the battle was over.

Meanwhile, six other Canadians originally with Carruthers' group had become separated from their unit during the fighting, and were stranded from the main force. Rather than surrender they fled on foot into the open veld (grassland), pursued by a group of Boers for two days, until finally the small band of Canadians was forced to stand and fight. Two were killed before the other four finally surrendered.

In total, 13 Canadians were killed and 40 wounded at the Battle of Boschbult, amid some of the fiercest fighting of the war.

Canadian Honours

The last of the Boers finally surrendered and the war ended on 31 May 1902. Canadian troops, in the first of many, and much greater conflicts to come in the 20th century, had distinguished themselves in South Africa. Their tenacity, stamina and initiative seemed especially suited to the Boers' unorthodox guerrilla tactics. Five Canadians received the Victoria Cross, 19 the Distinguished Service Order and 17 the Distinguished Conduct Medal. Canada's senior nursing sister, Georgina Pope, was awarded the Royal Red Cross. During the final months of the war, 40 Canadian teachers went to South Africa to help reconstruct the country.

Did you know?

In total, 12 Canadian nursing sisters served during the South African War. It was the first time Canadian women had been sent overseas with the military. Led by Georgina Pope, the volunteer nurses served with the British Medical Staff Corps. When the Canadian Army Medical Corps was established in 1904, it included a small, permanent nursing service.

Legacy

Overall, the war claimed at least 60,000 lives, including 7,000 Boer soldiers and 22,000 imperial troops. Approximately 270 Canadians died in South Africa, many of them from disease. Most of the suffering, however, was borne by civilians, largely due to disease resulting from poor living conditions among the tens of thousands of families confined in British concentration camps. An estimated 7,000–12,000 Black Africans died in the camps, along with 18,000–28,000 Boers, the majority of them children.

Despite the loss of life, at home Canadians viewed their soldiers' military feats with pride, and marked their victories during the war with massive parades and demonstrations.

Volunteer donors insured the veterans' lives upon their enlistment, showered them with gifts upon their departure and during their service, and feted them upon their return. They formed a Patriotic Fund and a Canadian branch of the Soldiers' Wives' League to care for their dependants, and a Canadian South African Memorial Association to mark the graves of Canadian dead — more than half of them victims of disease, rather than casualties of combat. After the war Canadians erected monuments to the men who fought. For most towns and cities across Canada, these were their first public war memorials, and many still stand today — including the South African Memorial on University Avenue in Toronto, sculpted by Walter Allward (who would later design the Canadian memorial at Vimy Ridge in France).

The war was prophetic in many ways — foreshadowing what was to come in the First World War: the success of Canada's soldiers in South Africa, and their criticism of British leadership and social values, fed a new sense of Canadian self-confidence, which loosened rather than cemented the ties of empire. The war also damaged relations between French and English Canadians, setting the stage for the larger crisis over conscription that would consume the country from 1914 to 1918.

South Africa also introduced new forms of warfare that would loom large in the future — it showed for the first time the defensive advantage of well-entrenched soldiers armed with long-range rifles, and it gave the world a foretaste of guerilla tactics.

Two towering figures of the 20th century also made appearances in South Africa: Winston Churchill, as a war correspondent, and Mahatma Gandhi, a Natal lawyer who volunteered as a stretcher-bearer, fetching Britain's wounded from the battlefields. Meanwhile John McCrae, the Canadian who wrote the famous poem “In Flanders Fields” in 1915, first tasted war in South Africa as a young officer with the Royal Canadian Artillery.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom