Victor Christian William Cavendish, 9th Duke of Devonshire, Governor General of Canada (1916–21)

Early Life and Education

Victor was the eldest son of Lord Edward Cavendish, a Liberal Unionist Member of Parliament for West Derbyshire, and Emma Elizabeth Lascelles. Edward was the younger son of William Cavendish, 7th Duke of Devonshire, but his older brother, Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, remained unmarried until the age of 59 and was childless. Victor was therefore expected to become Duke of Devonshire. He received his secondary education at Eton College and graduated from Trinity College, Cambridge, with a BA in 1891. After completing his degree, he studied accountancy and law in preparation for his roles as a politician and landowner.

Political Career in the United Kingdom

Upon the death of his father in 1891, the 23-year-old Victor succeeded him unopposed as the representative for West Derbyshire, becoming the youngest British Member of Parliament at the time. He was treasurer of the royal household from 1900 to 1903, and financial secretary to the treasury from 1903 to 1905. He served in the House of Commons until 1908, when he succeeded his uncle as Duke of Devonshire and took his seat in the House of Lords. During the First World War, he served as Civil Lord of the Admiralty from 1915 to 1916.

As Duke of Devonshire, he took an active role in local politics and the management of his estates, becoming Lord Lieutenant of Derbyshire and president of the Royal Agricultural society. The 1920 sale and demolition of his London residence inspired Siegfried Sassoon’s poem, “Monody on the Demolition of Devonshire House.”

Marriage, Family and Household

On 30 July 1892, Victor married Lady Evelyn Petty-Fitzmaurice, the elder daughter of Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, 5th Marquess of Lansdowne, Governor General of Canada from 1883 to 1889, and Lady Maud Hamilton.

The couple had seven children: Edward, Lord Hartington (later the 10th Duke of Devonshire) (1895–1950), Maud (1896–1975), Blanche (1898–1987), Dorothy (1900–66), Rachel (1902–77), Charles (1905–44) and Anne (1909–81). The six younger children accompanied their parents to Canada. During the family’s time in Canada, Charles was educated at Ashbury College in Ottawa while his sisters were tutored at home by governesses. Rachel became an accomplished skater and competed in figure skating competitions at the Minto Skating Club in Ottawa.

Devonshire was the last Governor General of Canada to maintain an entirely British household. His daughters Maud and Dorothy married his two aides-de-camp, Angus Mackintosh and Harold Macmillan. Maud married Mackintosh at Christ Church Cathedral on 3 November 1917, the first daughter of a Governor General to be married in Ottawa. The reception took place at Rideau Hall. Dorothy became engaged privately to Macmillan in 1919, and the couple were married in London in 1920. As Macmillan described in his memoirs, Winds of Change, “it was amidst the wonderful scenery at Jasper Park in Canada that I first knew my affections were returned.”

Spectators, including the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire, at a baseball game between the Epsom Canadians and London Americans in London, England (September 1916). Thousands of spectators watched as the team from the Canadian Convalescent Home in Epsom defeated the American team, which was composed of Americans who lived and worked in the city. The teams were part of the Military Baseball League established during the First World War.

Governor General of Canada

Devonshire was appointed as Governor General on the recommendation of British Prime Minister Herbert Asquith. Devonshire was initially reluctant to accept the appointment because of the opposition of his wife as well as his responsibilities in Britain but he was persuaded by his father-in-law Lord Lansdowne. The Duchess wrote to her husband’s aunt, “I never dreamt that Victor would accept and frankly was horrified when he went out to refuse and came home having accepted.”

The appointment was controversial in Canada because Asquith chose Devonshire on the basis of his rank in the peerage without consulting Canadian Prime Minister Robert Borden. (The previous Governor General, the Duke of Connaught, was a member of the royal family.) In his memoirs, Borden recalled that he sent “a cable to [Canadian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom Sir George] Perley commending the excellence of the choice but pointing out in strong terms that our approval should have been asked before the Duke was consulted.”

Borden came to admire the Governor General personally, stating, “No Governor General has come as an inheritor of finer traditions of public service or with a more comprehensive grasp of public questions as they touch not only this country and the United Kingdom, but the whole Empire.” Harold Macmillan recalled that Devonshire provided useful advice to Canadian politicians because of his own long experience in the British House of Commons and House of Lords, “Some of his Canadian Ministers used to tell me that when they first knew him they underestimated his knowledge, and the strength and shrewdness of his character… But the leading Ministers found in the Governor-General not merely a friend, but a useful political adviser.”

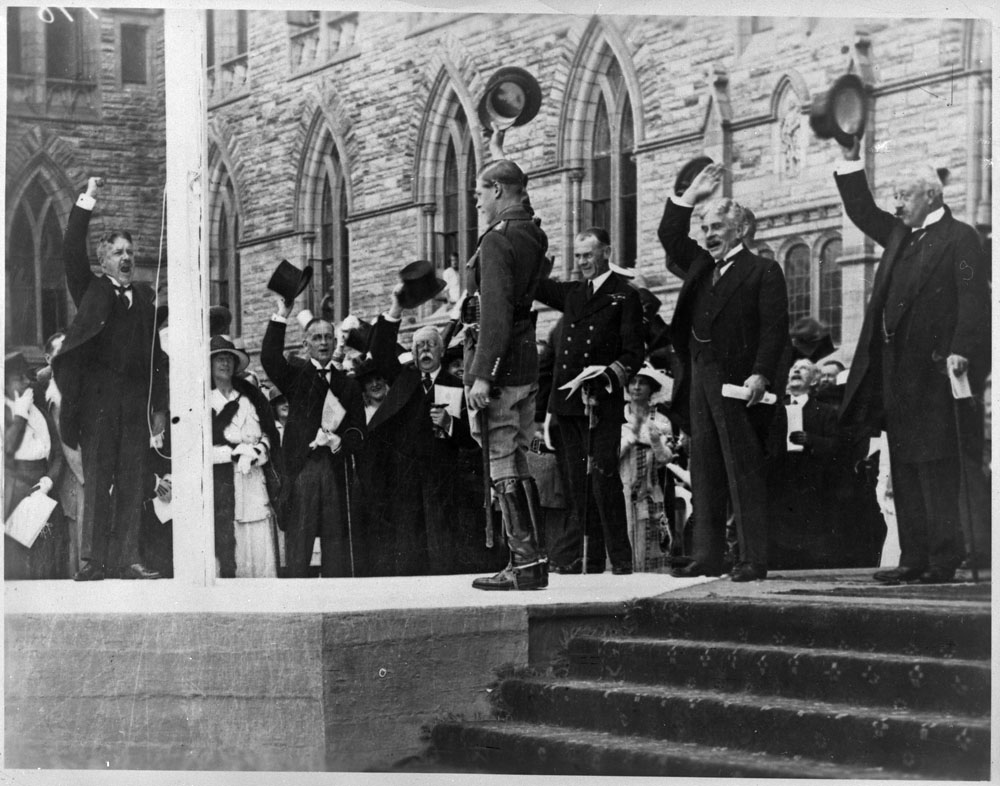

As Governor General, Devonshire presided over a number of public celebrations in Canada, including a modest ceremony in Ottawa to mark the 50th anniversary of Confederation in 1917, which Devonshire considered “quite dignified and appropriate to the occasion in wartime.” He also oversaw the joyous celebrations on Parliament Hill at the end of the First World War in 1918, and the cross country tour of the future King Edward VIII in 1919, who considered Devonshire to be “a damned good fellow.” Devonshire likewise admired the prince, writing to his mother, Lady Edward Cavendish, “He certainly has the capacity for doing the right thing in the right way. His speeches are quite admirable and everywhere he has created the most favourable impression.”

In 1916, during his first tour of Quebec, Devonshire received an honorary degree from McGill University. His acceptance speech honoured Canadian participation in the First World War, stating, “Whatever the cost to this generation we are determined it shall be carried on until such a peace is secured that future generations may be proud and grateful of the part we are taking in it.”

The Duke and Duchess of Devonshire had a warm friendship with the British Ambassador to the United States, Cecil Spring-Rice, whose wife, Florence Lascelles, was Devonshire’s cousin. The Devonshires visited the United States in 1918, meeting with President Woodrow Wilson at the White House. During Devonshire’s time as Governor General, Borden requested the appointment of a Canadian representative in Washington to represent Canada’s specific interests. Devonshire expressed cautious support for the proposal, suggesting that a Canadian representative could be attached to the British embassy. However, he was relieved when Spring-Rice found a diplomatic means to end the discussion by noting the difficulty securing a suitable residence for the proposed representative.

In 1920, Borden resigned as Prime Minister for health reasons and was succeeded by Arthur Meighen. Although Harold Macmillan, Devonshire’s son-in-law, admired how “firmly and effectively” Meighen had responded to the Winnipeg General Strike in 1919 while Borden represented Canada at the Paris Peace Conferences, Devonshire thought Meighen seemed “a little overwhelmed” by his responsibilities.

The Duke of Devonshire, Governor General of Canada, addressing members of the Volunteer Aid Detachment (VAD) of the St. John Ambulance, after the Halifax Explosion (21 December 1917, Halifax, Nova Scotia).

Canadian Tours and Interests

Devonshire traveled extensively in Canada during his term as Governor General, undertaking two official tours of western Canada, three tours of eastern Canada, including a 1917 visit to Halifax to inspect the damage following the Halifax explosion, and frequent tours of Ontario and Quebec. In Ottawa, Devonshire enjoyed attending hockey games and performances of the Ottawa Symphony Orchestra and Ottawa Choral Society. Devonshire especially enjoyed spending time in Quebec City, observing “a very great charm about the place,” and spent long periods at La Citadelle, his official residence there. Devonshire purchased a summer home at Blue Sea Lake in the Gatineau Hills where his family enjoyed canoeing and swimming. Devonshire was a nervous public speaker and especially dreaded making speeches in French. His daughter Maud wrote to her grandmother of his careful rehearsals of his French speeches to improve his pronunciation.

Devonshire took a strong interest in Canadian agriculture and enjoyed speaking with farmers across Canada. His own agricultural accomplishments as one of the most prominent landowners in the United Kingdom were recognized in the Canadian press. The Toronto Globe reported on Devonshire’s 1916 visit to the Ontario Agricultural College (now the University of Guelph), “It would have done the farmers of Canada good to see the way he judged a beast. Not a point was lost. Shorthorns at the college particularly interested him. He himself is a well-known breeder of that favourite English show stock…and has many a blue ribbon which his cattle have brought in.” Devonshire encouraged the development of experimental farms such as the Government of Canada’s experimental farm outside Ottawa and encouraged Canada to assume a leadership role in global agricultural research.

Titles and Honours Debate

As Governor General, Devonshire acted as mediator between the British and Canadian governments concerning the question of whether British titles and honours should be bestowed on Canadians. In 1918, Borden established a committee of the Privy Council to draw up an Order-in-Council proscribing hereditary titles as well as honours granted without the approval of the Canadian Prime Minister (with the exception of honours for military service). Devonshire received the Order-in-Council for approval and agreed with Borden that new hereditary titles were out of place in Canada, noting, “I believe there is strong feeling against creating such in Canada,” but offered no comment concerning whether existing hereditary titles should be eliminated.

The controversy placed Devonshire in a difficult situation as he saw both sides of the issue, defending increased Canadian jurisdiction over honours and titles as well as the royal prerogative throughout the British Empire. Devonshire wrote to the Colonial Secretary, “The [Order-in-Council] is partly designed to anticipate the introduction of a Bill by a private member [the Nickle Resolution of 1919] abolishing all titular honours. Present situation has been aggravated by honours recently granted to persons recommended from outside sources. I am of the opinion that the proposals of the minute in council should be accepted and thereby avert more drastic change.” Devonshire also wrote to King George V to explain that “the last thing which is intended is any lack of respect for Your Majesty.” The Order-in-Council and the subsequent Nickle Resolution brought an end to the King conferring honours on Canadian civilians for a decade and set precedents for the eventual development of a Canadian honours system.

Later Life

Devonshire wrote that when he left Ottawa for the last time in 1921, “It was really horrid and I could hardly help breaking down… Very unhappy to see the end of Ottawa.”

In 1922, Devonshire was offered the position of Secretary of State for India by British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, but he declined the post. Instead, he became Colonial Secretary in the cabinet of Andrew Bonar Law (the only British Prime Minister born in Canada) from 1922 to 1923. He was then chairman of the British Empire Exhibition from 1924 to 1925. The Canada pavilion at these exhibitions showcased Canadian industry including mineral mining and agriculture as well as tourist destinations such as Niagara Falls. David Lindsay, Earl of Crawford, observed in 1923, “There is a massive imperturbability about [Devonshire] which gives confidence. He will never let one down, never play for his own advantage.”

Devonshire suffered a paralytic stroke in 1925. According to his grandson, Andrew Cavendish, 11th Duke of Devonshire, the stroke changed his personality from “an easy-going, ironic, laconic man” to “one that was bad-tempered and difficult to get along with” and unwilling to speak directly with his wife, relaying messages by means of her secretary. He died at Chatsworth House in 1938.

Legacy

Devonshire was the last Governor General of Canada appointed without consultation with the Canadian government. The controversy surrounding his appointment meant that his successor, Viscount Byng, was chosen in consultation with Meighen.

In 1918, Devonshire donated the Devonshire Cup to the newly formed Canadian Seniors’ Golf Association. In 1921, he donated the Duke of Devonshire Trophy to the Ottawa Horticultural Society, which is awarded to the highest scoring exhibitor in the decorative classes. There is a public school in Ottawa named for Devonshire.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom