A reserve is land set aside by the Canadian government for use by First Nations. Reserves are managed under the Indian Act. Reserve lands represent a small fraction of the traditional territories First Nations had before European colonization. While reserves are places where members of a First Nation live, some reserves are used for hunting and other activities. Many First Nations hold more than one parcel of reserve land, and some reserves are shared by more than one First Nation. There are reserves in every province in Canada, but few have been established in the territories. Most reserves are rural, though some First Nations have created urban reserves, which are reserves within or neighboring a city.

This is the full-length entry about Reserves in Canada. If you are interested in reading a plain-language summary, please see Reserves in Canada (Plain Language Summary).

Reserves in Canada

For information specific to the history and location of reserves in different provinces and territories, as well as the society and culture of the Indigenous peoples who reside on those reserves, please see the following articles:

- Reserves in British Columbia

- Reserves in Alberta

- Reserves in Saskatchewan

- Reserves in Manitoba

- Reserves in Ontario

- Reserves in Quebec

- Reserves in New Brunswick

- Reserves in Nova Scotia

- Reserves on Prince Edward Island

- Reserves in Newfoundland and Labrador

- Reserves in the Northwest Territories

- In Yukon, 11 of the 14 First Nations in that territory are self-governing. Of the three First Nations in Yukon governed by the Indian Act, only one — Liard First Nation — holds reserve lands, according to the Government of Canada. (See also Self-Governing First Nations in Yukon.)

- There are no reserves in Nunavut. In this territory, created in 1999, the Inuit established a government and gained control of their land and resources.

What Is A Reserve?

Reserves are tracts of land set aside for First Nations by the Canadian government. First Nations are one of three groupings of Indigenous people in Canada, the other two being Métis and Inuit. Métis and Inuit do not hold reserve land. The reasons for this are complex, but lie primarily in the fact that the reserve system is governed by the Indian Act, and Métis and Inuit peoples’ relationship to the federal government is not.

Reserves can be large or small tracts of land, and most are in rural or remote areas. Some reserve lands are used for hunting and gathering, while others are home to residences and schools. A First Nation may hold and make use of more than one reserve. For example, Little Red River Cree Nation in Alberta uses two reserves: Fox Lake 162 and John D’Or Prairie 215. (See also Cree.) In some circumstances, more than one First Nation may share a reserve. Assabaska reserve in Ontario, for example, is used by both Big Grassy First Nation and Ojibways of Onigaming First Nation. Some First Nations, such as Qalipu Mi’kmaq First Nation in Newfoundland and Labrador, do not hold any reserve lands.

Who Lives on Reserves?

According to the federal publication, “Registered Indian Population by Sex and Residence, 2020,” there are 3,394 reserves in Canada set aside for more than 600 First Nations. Registered band members (those with Indian Status) have the right to live on-reserve. In 2020, approximately 50 per cent of these band members live on reserves. People without status may also live on a reserve, if the band council has adopted a residency bylaw that regulates the right to live on the reserve.

Governance of Reserves

Reserves should not be confused with traditional territories, which were lands used and occupied by First Nations before the arrival of Europeans. Reserves, which were created by colonial governments, are products of colonization in Canada. While reserves are seen as homelands for many First Nations peoples and provide a location for band council offices and governance, they are not “owned” by First Nations. The paramount authority over activities on reserves is granted to the federal minister responsible for Indigenous affairs in the Canadian government. (See also Federal Departments of Indigenous and Northern Affairs.)

Under the Indian Act, band councils have limited authority in terms of the administration and retention of the reserve. However, many First Nations are gaining more control of their reserve lands under the First Nations Land Management Act (1999). This Act gives First Nations the right to opt out of sections of the Indian Act relating to land management. It gives them the power to develop their own laws about land management on reserves. Other First Nations in Canada are pursuing self-government agreements, which sever First Nations from the Indian Act and give them authority over their own governance, membership and lands.

Origins of Reserves

Pre-Confederation

As early as 1637, Catholic missionaries in New France set aside lands within their seigneuries for the use and benefit of local First Nations. The missionaries expected that Indigenous settlement on these lands would assist them in converting Indigenous people to Catholicism. Colonial authorities assumed ownership of these lands with registered legal title. Since the concept of land title was not a part of Indigenous peoples’ world view, they would not have considered this land to be owned by the missionaries. The colonial practice of setting aside lands for Indigenous people while retaining legal title serves as the foundation of the reserve system in Canada.

As non-Indigenous settlement increased, tensions with Indigenous people over the use and occupation of traditional lands occurred. Following practices used by the Dutch in the Two Row Wampum treaty of 1613, English colonial governments used treaties as a method of acquiring Indigenous lands. Those policies were extended to Canada following the conquest of New France. The Royal Proclamation of 1763 acknowledged that Indigenous people had a title to the land. That title needed to be acquired by the Crown through negotiation prior to settlement and the enclosure of property. ( See also Aboriginal Title in Canada.)

In many cases before Confederation, Indigenous people were excluded from land surrendered by treaties and were forced to abandon their villages and move to lands not yet surrendered. (See also Upper Canada Land Surrenders.) As colonial governments acquired more and more Indigenous lands, it became common to include provisions in treaties to reserve some of the surrendered land for the use of the First Nations who had signed treaties. The title to the lands reserved under the terms of these early treaties was not entirely clear and, as a result, municipal governments, squatters and speculators used deceptive and unethical practices to obtain title to these reserved lands from the members of the band. Because of this, through a series of laws, the colonial government of Canada declared that the title to these reserves was retained by the Crown and thereby protected from taxation and alienation. In section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867, the federal government is assigned power over “Indians, and Lands reserved for the Indians.” The provisions of these early laws were incorporated into the Indian Act.

Post-Confederation

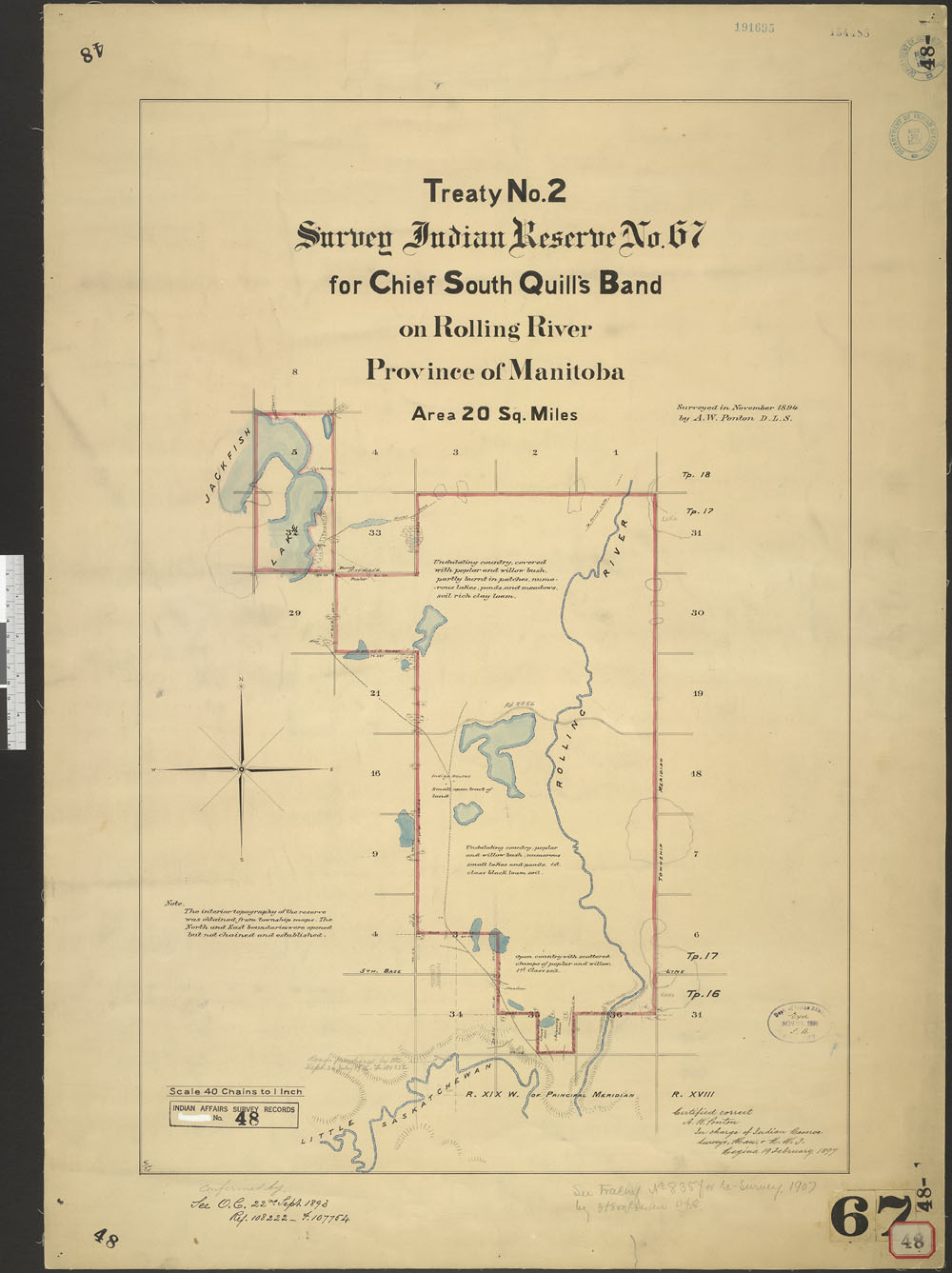

The setting aside of reserve lands through treaties continued in the Numbered Treaties, negotiated after Confederation. In these treaties, First Nations retained rights to continue to use the entirety of the surrendered tract for hunting, fishing and trapping. They also received reserves where First Nations people might live securely, obtain education and practise agriculture. The treaties provided that First Nations would select the location of their reserve, but the government occasionally rejected their selection and assigned them lands elsewhere. The size of the reserve promised to the First Nation varied between treaties.

There are numerous disputes about the designation of lands as reserves. For example, in Ontario, the reserve lands occupied by the Mohawk of the Bay of Quinte (Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory) and the Six Nations of the Grand River originated as special Loyalist grants following the American Revolution. As such, the Haudenosaunee dispute the legitimacy of Canadian laws imposing the Indian Act definition of a reserve on their lands. In British Columbia and Atlantic Canada, many reserves were established by colonial governments through orders-in-council rather than through any act of negotiation with Indigenous peoples. These reserves were often small and, after Confederation, were transferred to the federal government for the use and benefit of First Nations. In British Columbia, additional reserves were surveyed according to the colonial formula, leading to ongoing disputes in that province. The McKenna-McBride Royal Commission unsuccessfully tried to resolve problems related to reserves and they remain a topic of discussions in negotiations regarding Aboriginal title in that province.

Reserve Reductions and Land Claims

Prior to Confederation, colonial governments often took steps to reduce the size of lands reserved to First Nations. Colonial authorities in Upper Canada, for example, relocated many Anishinaabe from their reserves to Manitoulin Island through additional treaty negotiations. The new reserves on Manitoulin Island were subsequently reduced in size. (See also Upper Canada Land Surrenders; Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory.) In Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and British Columbia, the colonial governments simply reduced the size of reserves through government decision without any negotiation.

Post-Confederation, the Indian Act provided a set of rules to govern the practice of reducing the size of reserve lands. Under these rules, a majority of the members of a First Nation (in the original Indian Act, a majority of the male members) may surrender the band's interest in all or part of the reserve to the Crown. Canada is then required to manage the surrendered land for the benefit of the First Nation that surrendered it. Using these provisions in the Indian Act, the Canadian government obtained the surrender of reserve lands from First Nations throughout the country. As a result, the size of the reserve lands of many First Nations decreased significantly and many First Nations were forced to relocate their reserve lands to more isolated districts.

In 1991, the federal government established the Indian Claims Commission to address numerous land claims. (See also Specific Claims.) Many of these claims have been settled to the benefit of the First Nations, and the funds have been used in some cases to purchase lands and expand reserves. Occasionally, unresolved disputes about the surrender of reserve lands have led to violent confrontations such as those at Ipperwash and Caledonia. (See also 1492 Land Back Lane.)

Socio-Economic Conditions on Reserves

Given the varied nature of the origin, size and location of reserves, generalizations about reserve life are difficult. However, socio-economic problems seriously impact life on reserves. Although conditions are improving, First Nations on reserve continue to live below the standard of the Canadian population. The 2021 census found that 31.4 per cent of First Nation people on reserve lived in low-income households and that 21.4 per cent of First Nations on reserves lived in crowded housing.

Although reserves originated as locations where First Nations might pursue agriculture and education, many reserves ended up in isolated locations. That isolation meant that services such as access to water, sewers, electricity and housing have all failed to meet standards that most Canadians take for granted. Because management of reserve lands is retained by the Crown, First Nations have been unable to utilize their land and resources to secure economic development or fund social welfare. They are forced to rely on government funds for education, housing, social welfare and infrastructure. That funding is often inadequate.

With relatively few sources of economic activity and jobs on reserves, inadequate housing, a lack of safe and secure water, and a lack of reliable electricity and internet services, some First Nations peoples have decided to move away from the reserves. Both the Canadian government and First Nations seek to improve the socio-economic conditions on reserves, but it remains one of the most pressing challenges faced by Canadians and First Nations today.

For more information on the socio-economic conditions of Indigenous peoples in Canada, see Social Conditions of Indigenous Peoples in Canada, Economic Conditions of Indigenous Peoples in Canada, Health of Indigenous Peoples in Canada and Education of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.

Urban Reserves

Many First Nations peoples choose not to live on reserves because of the typical remoteness of reserves and the related challenges accessing various public services and gaining employment. Like most Canadians, many First Nations peoples live in Canada’s larger cities. Some First Nations have created urban reserves, which are reserves within or adjacent to a large city. Under the federal Addition to Reserve Policy, First Nations may obtain lands and have them added to their reserves. Utilizing this policy, urban reserves are being developed in many Canadian cities.

Among the first of such reserves is Asimakaniseekan Askiy of the Muskeg Lake Cree Nation. This urban reserve is located in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, on lands that were previously occupied by railways in the city. Asimakaniseekan Askiy is the result of a specific land claims settlement granted to the Muskeg Lake Cree Nation. It is home to dozens of Indigenous businesses in the city. The success of initiatives like this has led to creation of over 120 urban reserves across the country.

Self-Government

Many First Nation communities resent the federal government’s colonial oversight of their lands and the ways in which this stymies their ability to foster better social and economic conditions. Some initiatives have helped to provide First Nations with more direct control over their lands. The Framework Agreement on First Nation Land Management , for example, permits band councils to assume land management responsibilities. Additionally, Self-Government Agreements remove First Nations from the administration of the Indian Act. Bill C-92 further empowers First Nations by giving them control over children’s and social services on reserves.

Agreements reached through comprehensive land claims have provided First Nations with lands that are not reserves under the terms of the Indian Act. The James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement and Northeastern Quebec Agreement provided the Cree and Innu with Terres Reservée aux Cris and Terres Reservée aux Naskapi. Under the Yukon First Nations Land Claims Settlement Act, First Nation lands are defined as settlement land and are not reserves in the context of the Indian Act. (See also Self-Governing First Nations in Yukon.) Similarly, lands held by the Nisga’a, Tsawwassen and Tla’amin First Nations in British Columbia under their agreements are Indigenous lands rather than reserves.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom