Cholera

Cholera is an acute infectious disease of the intestines, acquired by consuming water or food contaminated by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. Cholera causes the production of severe watery diarrhea. Left untreated the disease can rapidly cause extreme dehydration, leading to kidney failure and possible death. A weak physical condition increases the likelihood of severe symptoms and possibly serious complications from the disease. Cholera is treated with electrolyte solutions, also known as oral rehydration salts, in order to replace lost nutrients from the body.

Cholera first reached Canada in 1832, brought by immigrants from Britain. Epidemics occurred in 1832, 1834, 1849, 1851, 1852 and 1854. There were cases in Halifax in 1881. The epidemics killed at least 20 000 people in Canada. Cholera was feared because it was deadly and no one understood how it spread or how to treat it. The death rate for untreated cases is extremely high. Grosse Île, near Québec, was opened in 1832 as a quarantine station and all ships stopped there for inspection.

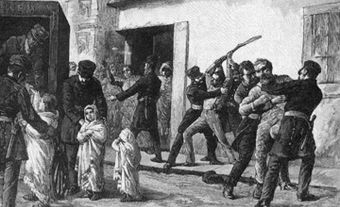

During epidemics, individual towns attempted to quarantine themselves against the disease. When quarantine failed to stop the disease, public health measures were taken by towns and provincial and colonial governments. The response to cholera encouraged governments to act to protect the health of Canadians and to provide for the sick. Not all the actions were popular and in some areas riots ensued, with crowds burning the cholera hospitals. Anger over cholera contributed to the antigovernment agitation in Lower Canada in the 1830s. Cholera was fairly common around the world prior to the advent of modern sanitation methods developed in the 20th century. Familiarity with the disease reduced the fear in later epidemics and a better understanding of how it spreads has made more effective prevention possible.

In the modern world cholera becomes endemic due to a lack of infrastructure and weak health care systems that lower the effectiveness of sanitation and contribute to conditions that allow the bacteria to thrive. The disease is common in refugee camps because of crowded and unsanitary conditions. South America had outbreaks of cholera in the 1990s and outbreaks continue to occur sporadically in southern Africa. Cholera is endemic in Malawi, Zambia and Mozambique. In Zimbabwe, deteriorating political conditions have also affected the social system and cholera is becoming endemic even in the nation's capital, Harare, where modern sanitation formerly helped prevent cholera. Medical professionals are attempting to improve public education about cholera prevention in regions prone to it, but without government investment in sanitation infrastructure, only limited success can be achieved.

The annual number of reported cases of cholera in Canada during 1995 to 2004 ranged from 1 to 8. Most cases in Canada result from international travel to an affected region. Cholera is considered a "reportable disease," which means that local, national and international health authorities must be notified upon discovery. Reporting diseases is an important practice for EPIDEMIOLOGY, which allows for disease monitoring and establishes patterns of occurrence around the globe. Other reportable diseases include active cases of TUBERCULOSIS, syphilis and HIV/AIDS.

See also EPIDEMIC.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom