The forcible expulsion and confinement of Japanese Canadians during the Second World War is one of the most tragic sets of events in Canada’s history. Some 21,000–22,000 Japanese Canadians were taken from their homes on Canada’s West Coast, without any charge or due process. Beginning 24 February 1942, they were exiled to remote areas of British Columbia and elsewhere. The federal government stripped them of their property and pressured many of them to accept mass deportation after the war. Those who remained were not allowed to return to the West Coast until 1 April 1949. In 1988, the federal government officially apologized for its treatment of Japanese Canadians. A redress payment of $21,000 was made to each survivor, and more than $12 million was allocated to a community fund and human rights projects.

This article is the full-length text on Japanese Internment in Canada. For a plain-language summary, see Internment of Japanese Canadians (Plain-Language Summary).

Terminology

These events are popularly known as the Japanese Canadian internment. However, various scholars and activists have challenged the notion that Japanese Canadians were interned during the Second World War. Under international law, internment refers to the detention of enemy aliens. But about 77 per cent of the Japanese Canadians involved were British subjects, and 60 per cent were born in Canada. (Before 1947, both people born in Canada and naturalized immigrants were considered British subjects; in other words, they were citizens of the Commonwealth. Canadian citizenship came into effect in January 1947.) Terms suggested instead include incarceration, expulsion, detention and dispersal.

Background: Anti-Asian Discrimination in Canada

Internment was a wartime measure enacted under the War Measures Act in the name of national security. However, it drew from a long history of anti-Asian racism and discrimination. Beginning at the turn of the 20th century, Japanese began arriving in Canada in visible (though still small) numbers. White people in British Columbia protested their presence through legal discrimination and acts of violence.

In 1902, in response to a court challenge, the British Privy Council confirmed an earlier provincial law; it stated that Asians in British Columbia, whether they were British subjects or not, were barred from voting on racial grounds. (See Right to Vote in Canada). The province also tried to limit immigration through legal devices; but these were voided by the federal government, which was sensitive to diplomatic relations with Japan.

In September 1907, anti-Asian sentiment in Vancouver erupted in a violent riot. White people marched through Chinese and Japanese neighbourhoods. They broke windows and assaulted residents. In response, Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier’s government negotiated a “gentlemen’s agreement” with Japanese officials. It limited immigration from Japan to 400 people per year. This amount was reduced to 150 in 1928.

Second World War and “Enemy Aliens”

After Canada declared war on Germany in September 1939, political leaders in Ottawa introduced a military draft for home defence. Political leaders in British Columbia insisted that Nisei (Canadian-born people of Japanese ancestry) be excluded from any conscription. If Japanese Canadians were called for military service, they would have a strong argument for voting rights. Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, who considered Japan a potential enemy, agreed to exclude Japanese Canadians from the draft.

In March 1941, Ottawa required all Japanese Canadians, whether they were British subjects or not, to register with the government. This policy was based on a recommendation from the Special Committee on Orientals, a federally-appointed advisory group. In effect, this declared Japanese Canadians to be enemy aliens.

DID YOU KNOW?

The term enemy alien referred to people from countries, or with roots in countries, that were at war with Canada. During the First World War, this included immigrants from the German, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires and Bulgaria; during the Second World War, people with Japanese, German and Italian ancestry. (See also Internment in Canada; Ukrainian Internment in Canada.)

The Japanese raid on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 brought the United States into the Second World War. (See also Canada and the Battle of Hong Kong.) It also triggered war between Canada and Japan, and unleashed hostility against Japanese Canadians. White farmers, merchants and political leaders seized the opportunity to rid themselves of their long-despised competitors. They accused Japanese Canadians of being spies and saboteurs. They called for drastic action to protect the West Coast. On 16 December 1941, Vancouver Sun journalist Bruce Hutchison warned Jack Pickersgill, Prime Minister King’s advisor, of widespread calls for arbitrary action: “We are under extraordinary pressure from our readers to advocate a pogrom [an organized massacre] of Japs.”

Japanese Canadian fishermen were required to turn in their boats, which were later sold by the authorities. But there were no mass arrests or immediate action. The RCMP found no evidence of sabotage or military threat. The chiefs of the Canadian Army and Navy vigorously denied that Japanese Canadians posed a danger or threat of any importance. However, a cabal of politicians and lobbyists in British Columbia began campaigning for the removal or confinement of Japanese Canadians in the coastal regions.

Growing Pressure for Removal and Detention

In late December 1941, British Columbia’s new Liberal premier, John Hart, and Conservative attorney general, R.L. Maitland, publicly called on the federal government to “remove the menace of Fifth Column activity from B.C.” Major General R.O. Alexander, head of the Pacific Command, wrote to his superiors that, “Public feeling is becoming very insistent, especially in Vancouver, that local Japanese should be either interned or removed from the coast.”

The anti-Japanese pressure from the West Coast was so strong that the federal Cabinet ordered an inquiry. On 8–9 January 1942, a Conference on Japanese Problems took place in Ottawa. It was attended by the Standing Committee on Orientals (formerly the Special Committee); a group of federal and BC Cabinet members; Army officials; BC provincial police and RCMP authorities; and delegates from the Department of External Affairs.

Many of those present were skeptical of the Standing Committee members and their advocacy of internment. Hugh Keenleyside, a veteran diplomat who had served several years in Tokyo, argued that there was no good reason for mass action. He suggested such a policy might endanger Canadian prisoners of war in Japanese hands. (See Canada and the Battle of Hong Kong). Major General Maurice Pope, vice-chief of the General Staff, was disgusted when a BC politician told him privately that his constituents saw war with Japan as a heaven-sent excuse to eliminate Japanese Canadian economic competition.

Those at the conference were bitterly divided on the matter of forced removal. The majority opposed the idea; they even suggested that Nisei be permitted to form a civilian corps to show their loyalty.

Expulsion and Detention

Political pressure from the West Coast, led by federal Cabinet minister Ian Mackenzie, caused the government to act. On 14 January 1942, Prime Minister Mackenzie King ordered the removal of all adult males of Japanese ancestry from the coast. The government ordered that the men be sent to work in road labour camps. But they were unable to leave immediately because of the winter weather. Though meant as a compromise, such official action implied that there was an actual threat from Japanese Canadians. It thus heightened the fears of white people on the West Coast; it encouraged them to press for the removal of all Japanese Canadians.

King feared mass riots that would lead to reprisals against Canadian soldiers held prisoner by Japan. He also shared popular views that saw all Japanese as treacherous. He wrote in his diary that he agreed entirely with Chinese official T.V. Soong. Soong had proclaimed that he would not trust any Japanese, even naturalized or Canadian-born, as they were all saboteurs just waiting for the right moment to aid Japan.

On 19 February 1942, US President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. It authorized the military to exclude all ethnic Japanese from the West Coast. Canadian leaders felt both empowered and required to take similar action. On 24 February 1942, Cabinet approved Order-in-Council P.C. 1486. Prime Minister Mackenzie King announced it the next day: all people of Japanese ancestry would be excluded from a 100-mile zone inland from the Pacific Coast.

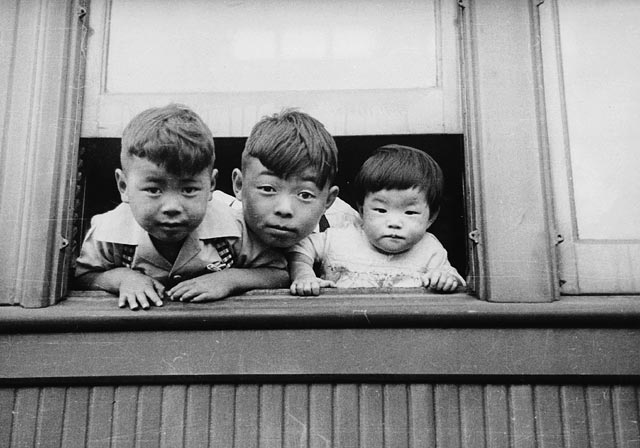

The Order led to the expulsion of some 21,000 Japanese Canadians from their homes. Around 77 per cent were British subjects, and 60 per cent were Canadian-born. A new government agency, the British Columbia Security Commission, was created to run the removal operation. Able-bodied Japanese Canadian men were ordered to report for transportation to road labour camps. All other men, plus women and children, were brought to Vancouver. They were divided by sex and housed together on cots in a former women’s building and in livestock barns on the grounds of the Pacific National Exhibition. (See Japanese Canadians Held at Hastings Park.)

The horror of having families forcibly separated led a group of Nisei to form the militant Nisei Mass Evacuation Group. In a series of public speeches and petitions, they demanded removal in family groups to government-built and -maintained centres. This was the same treatment Japanese Americans were getting. By refusing to show up for transportation to road labour camps (and hiding out within Vancouver), or by surrendering themselves and demanding internment as enemy aliens, they were able to get the government to agree to family relocation. In the process, around 700 Japanese Canadian men were targeted as troublemakers and sent to a prisoner of war camp in Ontario.

Mass Confinement

By late summer 1942, all Japanese Canadians had been moved from the West Coast. Around 2,150 single men were sent to work on road labour camps. Another 3,500 Japanese Canadians opted to sign contracts to work on sugar beet farms outside British Columbia. (See Sugar Industry.) They served as exploited labourers, and thereby remained “free.” Some 3,000 more affluent Japanese Canadians were permitted to leave the coast in groups and settle in so-called “self-supporting projects” at their own expense.

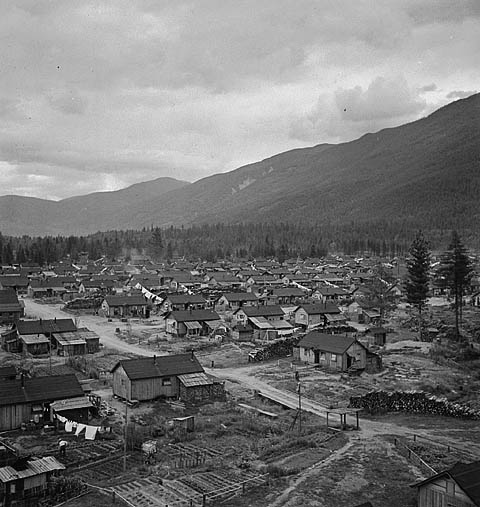

However, the majority of Japanese Canadians, some 21,000–22,000 people, were exiled to the Slocan Valley, in BC’s eastern Kootenay region. They were housed in what were euphemistically called “interior housing centres.” These were mainly in largely-abandoned mining towns (e.g., New Denver, Kaslo, Greenwood and Sandon); or in a government-built camp called Tashme, near the town of Hope, in the Fraser Canyon.

Once moved to the Slocan Valley, they lived in abandoned houses hastily refitted by the government, or in newly-built shacks. The housing was hastily put together and did not protect against the frigid weather. Except for producing shelter, the government did not provide the inmates with any financial assistance. In the United States, the camps offered basic food, clothing and education. But Canadian officials provided no food or clothing, and no schooling above the elementary level. (See also Hide Hyodo Shimizu.) Ultimately, some Christian groups opened up high schools in the settlements. The government hired some Nisei to cut wood, but in general people had to find such work as they could or live off their savings.

Dispossession and Detention

The federal government confiscated the property and personal possessions of the Japanese Canadians. This was done to finance the costs of their internment and to discourage them from returning to the West Coast. After amending the powers of the Custodian of Enemy Property, the government issued an order-in-council on 23 January 1943. It permitted the forced sales of Japanese Canadians’ property.

In March 1943, G.W. McPherson, the Vancouver representative of the Custodian of Enemy Property, publicly announced that he would dispose of all Japanese Canadian property in his care. This included personal possessions and land. The news attracted significant protest, both among Japanese Canadians and others. But on 23 June 1943, 769 properties belonging to Japanese Canadians, and their rental income, were taken over by the Veterans Land Administration for $850,000. (See Veterans’ Land Act.)

Smaller transactions continued over the next four years. The Custodian disposed of inmates’ personal property at very low prices. The government held the money in accounts for those in the camps, paying no interest, and limited their withdrawals to $100 per month. Japanese Canadians were forced to use the funds to pay for their confinement.

Dispersal and Deportation

After 1942, the Canadian government pushed Japanese Canadians to resettle east of the Rocky Mountains at their own expense. However, government agencies still controlled the lives and businesses of Japanese Canadians, even when they moved out of the restricted area.

In 1945, as Japanese Americans began to leave the US government camps and return to the West Coast in large numbers, Prime Minister Mackenzie King issued a new order-in-council. It gave Japanese Canadians two options: resettle outside of British Columbia, with a minimum of government assistance; or sign up for “voluntary repatriation” to Japan once the war ended. In the latter case, they could stay where they were and receive financial assistance. Though officially neutral, Ottawa’s policy was designed to pressure Japanese Canadians into giving up their British subject status and leaving the country.

The majority of Japanese Canadians agreed to move east of the Rockies, though they still faced legal restrictions. However, once the war ended in August 1945, Ottawa issued orders to deport the 10,000 people who, by refusing to move, were deemed to have “agreed” to “voluntary” repatriation. Japanese Canadians and their allies, notably the Toronto-based umbrella group Co-operative Committee on Japanese Canadians (CCJC), mobilized to block this deportation. The matter went to the Supreme Court of Canada and later to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council — at the time the highest appeals court in the Canadian judicial system. It upheld the constitutionality of this involuntary deportation.

King ultimately dropped the policy in the face of public opposition. But almost 4,000 people were still shipped to Japan. Many had to wait for years before they could return. Meanwhile, the government maintained the wartime restrictions on Japanese Canadians. They were not allowed to return to the West Coast until 1 April 1949.

Redress Movement

During the postwar years, Japanese Canadians and their allies began lobbying for compensation for their wartime treatment. In 1946, the Japanese Canadian Committee for Democracy did a survey among Toronto-based Japanese Canadians. It found that property worth an estimated $1,400,395.66 had been sold for $351,334.86.

In response to public pressure, the government issued Order-in-Council P.C. 1810 on 18 July 1947. It established a commission, led by Justice Henry Bird of the British Columbia Supreme Court, to inquire into fraud and mishandling by the Custodian of Enemy Property. In spring 1950, the Bird Commission produced its report. It found that the amounts paid to Japanese Canadians for their properties were substantially below fair market value. The report recommended a payment of $1,222,929.26 to cover losses on some 2,400 claims. In the end, Japanese Canadians were generally unable to recover much of their losses.

The wartime treatment of Japanese Canadians remained a largely taboo subject throughout the postwar years. In a 1961 television interview, former Prime Minister Louis St-Laurent defended the removal decision on racial grounds, stating that, “Blood is thicker than water.” In 1964, however, Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson publicly referred to the confinement as “a black mark” in the nation’s history.

During the 1970s, Japanese Canadians, like their counterparts in the United States, began to organize remembrances and educational campaigns. The National Association of Japanese Canadians (NAJC) and other groups started a campaign for reparations. However, this so-called “redress movement” met with official resistance. Canadian war veterans who had been confined in Japanese prisoner of war camps during the war opposed reparations for Japanese Canadians. Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, though he expressed public regret for the wartime actions, remained opposed to compensation.

The Conservative government of Brian Mulroney was sympathetic to claims by Japanese Canadians. It opened negotiations in the mid-1980s. However, the government hesitated to place a dollar amount on a settlement. Activists debated whether to press for individual payments or a collective settlement. In mid-1988, Mulroney assigned Secretary of State Lucien Bouchard to broker an agreement.

In September 1988, about six weeks after a similar redress bill was enacted in the US, an agreement was reached in Canada. The terms of the Canadian settlement included an official apology; a redress payment of $21,000 to each surviving individual affected by official policy; a community fund of $12 million; and funding for a Canadian Race Relations Foundation to support human rights projects.

See also Internment in Canada; Interned in Canada: An Interview with Pat Adachi; Hide Hyodo Shimizu; Obasan (novel); Joy Kogawa; David Suzuki; Masumi Mitsui; Vancouver Asahi; Racial Segregation of Asian Canadians.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom