Métis are people of mixed European and Indigenous ancestry, and one of the three recognized Aboriginal peoples in Canada. The use of the term Métis is complex and contentious, and has different historical and contemporary meanings. The term is used to describe communities of mixed European and Indigenous descent across Canada, and a specific community of people — defined as the Métis Nation — which originated largely in Western Canada and emerged as a political force in the 19th century, radiating outwards from the Red River Settlement (see Métis Are a People, Not a Historical Process and The “Other” Métis). While the Canadian government politically marginalized the Métis after 1885, they have since been recognized as an Aboriginal people with rights enshrined in the Constitution of Canada and more clearly defined in a series of Supreme Court of Canada decisions.

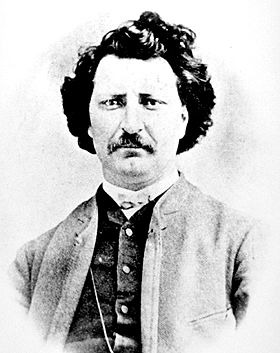

(courtesy Provincial Archives of Manitoba/N-5733)

Definitions and Terminology

Editorial Note: In the interest of promoting a better understanding of the complex issue of Métis identity and how it is defined, The Canadian Encyclopedia has commissioned two opinion pieces exploring different perspectives on the topic. Métis Are a People, Not a Historical Process explores Métis identity from the perspective of Métis with ancestral ties to the Red River Settlement. The “Other” Métis explores Métis identity from the perspective of Métis who do not have ancestral ties to the Red River Settlement.

The use of the terms “Métis” and “métis” is complex and contentious. When capitalized, the term often describes people of the Métis Nation, who trace their origins to the Red River Valley and the prairies beyond. The Métis National Council (MNC), the political organization that represents the Métis Nation, defined “Métis” in 2002 as: “a person who self-identifies as Métis, is distinct from other Aboriginal Peoples, is of historic Métis Nation ancestry and who is accepted by the Métis Nation.” The MNC defines the Métis homeland as the three Prairie provinces and parts of Ontario, British Columbia, the Northwest Territories and the northern United States. Members of the Métis Nation have a common culture, ancestral language (Michif), history and political tradition, and are connected through an extensive network of kin relations.

The Congress of Aboriginal Peoples (CAP) has been critical of this definition of Métis, asserting that it excludes “many people who have legitimate claims to Métis identity.” Despite CAP’s stance, the MNC’s position is the one that has generally been adopted by federal and provincial governments and the courts. For example, Métis Aboriginal rights defined in the Powley decision and section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 have only been applied to Métis communities west of Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. While several lawsuits claiming section 35 Métis rights have been brought before the courts by other communities, none have been successful. For example, R. v. Vatour in 2010 ruled against the notion of a Métis community in the Maritimes. Further, the implementation of these rights defined by the Powley decision and by various provincial governments all fall within the MNC's definition of the "Métis Homeland, " which includes the Prairie provinces, and parts of Ontario, BC and the NWT.

Typically, when written with a small-m, métis refers to any community of European-Indigenous ancestry, including those in Ontario and Québec and non-status settlements near First Nations reserves. It is often used to describe mixed-descent families and communities during the 18th and early 19th century Great Lakes fur trade, although some scholars now avoid using the term.

Contemporary usage of Métis is also different from its historical meaning. At Red River in the 19th century there were two prominent communities of mixed-descent people. In addition to a sizeable French-speaking and nominally Catholic Métis population, there was a large group of English-speaking “Half-breeds” who were mainly Anglican agriculturists. While these interrelated communities can be considered to be distinct constituencies — even though the boundaries between them were quite porous — the derogatory nature of the term “Half-breed” has caused it to fall largely into disuse. Thus, the contemporary meaning of “Métis” typically includes people of both French- and English-speaking heritage.

There are also Canadian legal definitions that further complicate Métis terminology. Section 35(2) of the Constitution Act, 1982 recognizes “ Indian, Inuit and Métis peoples” as Aboriginal peoples under Canadian law, yet despite several Supreme Court of Canada decisions, Métis Aboriginal rights — and who may possess these rights — remain, for the most part, undefined. However, in 2016, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled in the Daniels case that the federal government has jurisdiction over Métis people, and that both members of the Métis Nation and Non-Status Indians are “Indians” as defined by the Constitution Act. The Court stopped short of clarifying the legal definition of Métis, but removed one barrier governments used for generations to avoid dealing with outstanding Métis issues.

Take the quiz!

Test your knowledge of Indigenous peoples by taking this quiz, offered by the Citizenship Challenge! A program of Historica Canada, the Citizenship Challenge invites Canadians to test their national knowledge by taking a mock citizenship exam, as well as other themed quizzes.

Métis Communities in Canada

There are people of mixed ancestry throughout Canada. The earliest mixed Indigenous-European marriages can be traced to the earliest days of contact, yet whether these marriages resulted in distinct Métis communities has long been the subject of scholarly debate. Some academics have argued that any mixed-descent person should be considered Métis. However, other scholars, along with the MNC, suggest that only those who were part of distinct Métis communities and used the term “Métis” in a self-referential way, should be called Métis. “Labrador Métis” for example, have dropped Métis for this reason and instead prefer a term their ancestors used to define themselves: NunatuKavut. Scholars who defend the Red River definition of “Métis” argue that Métis identity is not simply the result of a dual heritage, but rather a matter of possessing a singular cultural heritage of dual origins; someone of Cree and French Canadian descent would be considered Métis not solely by virtue of their mixed-descent, but whether they have Métis heritage that can be traced back to the Red River community.

Others have argued that such a narrow definition offers a limited understanding of Métis history. Communities in Ontario and Eastern Canada that have sought official recognition as Métis, for example, have expressed frustration at the popular notion that a traceable ancestry to the Red River settlement is a necessary requirement to “authentically” identifying as Métis. They argue that mixed-descent families and communities have existed since the 18th and early 19th century Great Lakes fur trade, before the establishment of the Red River Settlement. However, for many Red River Métis, the term is an important part of their specific history, heritage and identity, as enshrined by Canadian law. This remains an issue of heated debate among many métis people in Canada. (See The "Other " Métis; Métis Are a People, Not a Historical Process).

Great Lakes Communities

The first small-m métis communities emerged during the Great Lakes fur trade in the 18th century. Great Lakes Indigenous diplomatic and economic protocols encouraged French fur traders to establish family connections through marriage and ceremonial adoption with prominent Indigenous families in the region. Such unions with Indigenous women — referred to as marriages à la façon du pays, “according to the custom of the country” — usually involved mutual commitments with local Indigenous kin and communities. French traders often lived out their lives with these families, whether formally employed at the forts or subsisting as gens libres (French and Métis freemen who supplied the posts or served intermittently as guides, interpreters or voyageurs). Game, fish, wild rice and maple sugar furnished sustenance, supplemented by small-scale slash-and-burn agriculture. Over time small groups of mixed families situated themselves in specific economic niches, with many rising to economic and social prominence throughout the Great Lakes region.

Scholarship has suggested that the application of the term “métis” to the Great Lakes region at this time is problematic since these mixed communities favoured terms like Saulteurs, bois brûlés (literally “burnt wood”), or chicots. While the term “métis” appears occasionally in contemporary writing, it was used predominantly by outsiders to make sense of a complex set of relationships between Indigenous communities and their relatives, not necessarily by the Great Lakes “métis” themselves. Likewise, the term “Métis” did not make its way into common language at Red River until the early 19th century, several years after the decline of the Great Lakes fur trade and the mixed communities it supported. Despite this distinction in terminology, the Métis of Red River and the métis of the Great Lakes were often connected through marriage and kinship practices.

The Western Métis

The success of the fur trade in the region that the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) called Rupert’s Land also relied on intermarriage. While the Company initially attempted to suppress these “country marriages,” the effectiveness of these unions in establishing trade networks, along with the successful use of intermarriage by the rival North West Company (NWC), convinced the HBC to modify its policy. Initially, the children of these marriages lacked the distinct community and economic base upon which to build a separate identity. While some HBC officers' mixed children were educated in England, Scotland or in the Canadas (see Upper and Lower Canada, later the Province of Canada), and other families were left in the care of other HBC employees when senior officers returned to Europe, not all mixed-descent children faced difficult prospects. Many of these mixed-descent children remained in the North-West, living near one another and developing a sense of themselves as a unique cultural and social community. This sense of self would eventually evolve into a sense of political commonality.

It was in the Red River region and on the prairies that the Métis began to make their mark on Canadian history. By 1810 they had established roles as buffalo hunters and provisioners to the NWC. As NWC supply lines lengthened to Athabasca and beyond, the Red River heartland became crucial to the Montréal-based traders as a provisioning centre. Accordingly, in 1811, Thomas Douglas, Earl of Selkirk, reached an agreement with the HBC to found the agricultural colony of Assiniboia for Scottish settlers with the ultimate goal of provisioning the HBC. The early Métis were allied with the Nor’Westers, and saw the colony as a direct threat to the NWC’s trade and thus their own livelihood.

Nor'Wester William McGillivray admitted in a letter of 14 March 1818 that the Métis were linked to the NWC by occupation and kinship. “Yet,” he emphasized, “they one and all look upon themselves as members of an independent tribe of natives, entitled to a property in the soil, to a flag of their own, and to protection from the British government.” Further, it was well proved “that the half-breeds under the denominations of bois-brûlés and métifs have formed a separate and distinct tribe of Indians for a considerable time back.”

The early Red River Colony did not allay these fears, but rather antagonized the Métis and the NWC. Decrees from the governor of the colony forbade the export and sale of pemmican to anyone but local HBC forts, and later banned hunting buffalo from horseback (see Pemmican Proclamation). These were direct economic sanctions against Métis families who provisioned the NWC with pemmican made from buffalo meat (which had been hunted on horseback). After escalating raids on rival fur trade forts by HBC and NWC officers, many prominent Métis grew hostile to the Selkirk settlement’s leaders and, under the leadership of Cuthbert Grant, in 1815 decided to evict the settlers from the region. In 1816, after Selkirk himself had decided to evict the Nor’Westers, the governor of the settlement, Robert Semple, confronted a group of Métis soldiers at Seven Oaks. A battle broke out and the Métis soldiers killed Semple and several colonists. The event was memorialized in Pierre Falcon’s “La Chanson de la Grenouillère.” (See also: Music of the Métis.)

The Battle of Seven Oaks resulted in an agreement between Cuthbert Grant and the Selkirk settlement’s interim leader, Peter Fidler. By 1821, any inter-company conflicts were ended with the merger of the HBC and NWC. After the merger a number of traders were deemed redundant and many took up residence at the Red River Colony, which thus gained an increasing Métis presence. Company employees with Métis families lobbied for the founding of a community where they could retire and have lands, livelihoods, schools, churches and other amenities. The HBC itself hoped to reduce costs by relocating dependent populations to a place where they could become self-supporting under the Company's governance.

From 1821 to 1870, Red River's overwhelmingly mixed-descent population continued to reflect its dual origins: Montréal, the Great Lakes and Prairies, and the NWC; and Britain, the Scottish Orkney Islands (a major HBC recruiting ground) and Rupert's Land. Some argue that these groups expressed mutual solidarity on the basis of their numerous intermarriages, business ties, shared involvements in the buffalo hunt, the HBC transport brigades and provisional government of 1869–70. A contrary view emphasizes the split between Roman Catholic francophones and Protestant anglophones. Whatever their internal ties and tensions, the rapidly growing population in the Northwest was, by the 1830s, increasingly seen as a racial aggregate, as racially based interpretations of human behaviour reigned in the 19th century. As such, Métis were often limited in their advancement through Company ranks.

While the HBC claimed to govern the population of Red River through the Company-appointed Council of Assiniboia, it governed more through influence than command. Throughout the 1840s and 1850s, Métis challenged the HBC trade and administrative monopoly in Red River. In 1849 Métis disrupted the trial of free trader Pierre-Guillaume Sayer, effectively ending the HBC fur monopoly and ushering in an era of free trade. In the mid-1850s, Métis petitioned the Imperial Government in London through Red River-born lawyer Alexander Kennedy Isbister to limit the Council of Assiniboia’s power. On the ground, the Council rarely commanded enough of a constabulary to compel Métis to follow its laws, so the Council was often forced to compromise with the community to ensure the enforcement of its laws.

The Red River Provisional Government, 1869–70

Other events overshadowed Métis-Company disputes in the 1860s: the intensifying eastern interest in developing the West (heightened by Henry Y. Hind’s glowing report of its agricultural potential); and Confederation in 1867. In 1869 the Dominion of Canada and the HBC reached an agreement for the transfer of Rupert's Land to the Canadian government. Among Métis, however, questions arose on how the Company had gained ownership of the Northwest, when a multitude of “natives of the country” including the Métis and their Cree, Saulteaux and Assiniboine relatives still possessed a claim to the territory as descendants of the original inhabitants. Well aware of British plans to transfer their country to Canada, Métis leaders generally rejected the notion that a transfer was possible without the consent of the Indigenous peoples who lived there and strategized methods of resistance at several public assemblies in 1869. The armed conflict that ensued is known as the Red River Resistance or Red River Rebellion.

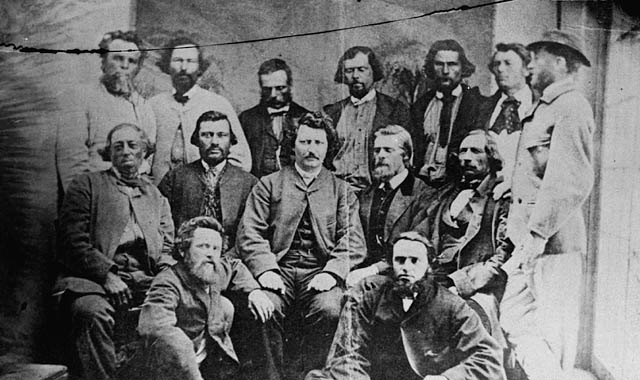

The consequent efforts of government surveyors to map Red River without regard for local residents' holdings resulted in the establishment of the Métis National Committee, and a provisional government in late 1869. These events established Louis Riel as the leader of the Métis resistance (see also: Louis Riel Timeline). After consolidating their alliance with the “Half-breed” population and the old British settler population, the three constituencies formed the Provisional Government of Assiniboia’s Legislative Assembly in March 1870, and sent a delegation to Ottawa to negotiate Red River’s entrance into Confederation. The outcome was the Manitoba Act, which established Manitoba as a new province in Confederation as well as several other commitments to protect Métis landholdings (including a 1.4 million acre land reserve), language and local political control over the new province.

However, the agreement recorded by the Provisional Government’s chief negotiator varies in important ways from the Manitoba Act, and Métis leaders have argued since the 19th century that the original agreement has never been properly implemented. The promised land reserve was never properly allotted; and when it was, it was granted piecemeal to individual families, taking well over a decade to be allocated. The settlers and troops who arrived in the new province after 1870 were generally hostile to the Métis, many of whom were “beaten and outraged by a small but noisy section” of the newcomers, according to a report by the new governor, Adams Archibald. Métis landholders were harassed, while new laws and amendments to the Manitoba Act undermined Métis power to fend off speculators and new settlers.

Of the approximately 10,000 persons of mixed descent in Manitoba in 1870, two-thirds or more are estimated to have departed in the following few years. While some went north and some went south to the United States, most headed west to the existing Métis settlements around Fort Edmonton (Lac Ste Anne, St Albert and Lac La Biche) and to the South Saskatchewan River, where they joined many Métis families already living at St Laurent, Batoche and Duck Lake.

The North-West Resistance

As Saskatchewan Métis communities grew due to the Manitoba exodus, several sought to clarify their land titles with the Canadian government. The government ignored Métis concerns while negotiating major Indigenous treaties and pre-empting land for railways. In deep frustration, the Saskatchewan Métis took up arms under Riel and Gabriel Dumont in the North-West Resistance of 1885.

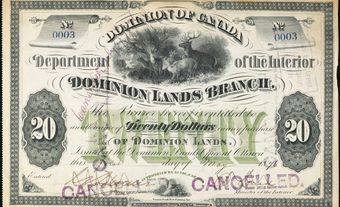

The Métis defeat at Batoche and the execution of Riel for treason set off a second dispersal, particularly to Alberta, and a renewed weakening of political influence and cohesiveness ( see also: Battle of Batoche). Sir John A. Macdonald in 1885 articulated a view that would begin the process of denying Métis identity for the next century: “If they are Indians, they go with the tribe; if they are half-breeds they are whites.” Where Métis individuals did receive land allowances (or financial equivalents), they usually were granted them in paper scrip — transferable certificates which unscrupulous speculators often pressured them to sell cheaply on the spot. The “scrip hunters” followed the Treaty No. 8 Half-Breed Commission in 1900 as it made its awards to Métis in the Dene settlements, and bought up many $240 scrip certificates for cash amounts of $70 to $130.

From 1885 to the mid-1900s, poverty, demoralization and racism commonly connected to being identified as a “half-breed” led many Métis to deny or suppress that part of their heritage if they could. In 1896 Father Albert Lacombe, concerned for Métis interests, founded St-Paul-des-Métis northeast of Edmonton on land furnished by the government. For financial and other reasons, the colony failed as a formal entity by 1908, and settlers from Québec began to dominate the area. The multiple dispersals of Métis families across the west has led to the existence of Métis communities across the Prairies, and into British Columbia and the Northwest Territories, as well as the northern United States and northwestern Ontario.

20th Century Métis Activism

Despite the struggles of the 19th century, some developments after 1900 were more positive. In 1909, the Union nationale métisse St-Joseph de Manitoba, founded by former associates of Riel and others, began to retrieve (from Métis documents and memories) their own history of the events of 1869–70 and 1885, resulting in A.H. de Trémaudan's classic work, Hold High Your Heads: History of the Métis Nation in Western Canada (1936). The 1920s and 1930s saw the rise of new leaders — notably James Patrick (Jim) Brady and Malcolm Norris — who, as Prairie socialist activists, built a new political and organizational base to defend their people's interests. Many Métis and non-Status Indigenous peoples had been considered “squatters” (although they asserted title of their own to these lands) on Crown lands in Alberta. Threatened by a federal plan to place these lands under provincial jurisdiction, Joseph Dion and others organized petitions and delegations to the Alberta government to seek land title for the Indigenous peoples living there.

After Brady and Norris joined the movement in 1932, the first of several provincial organizations was founded — the Métis Association of Alberta, open to all persons of Indigenous ancestry. Its efforts led to the appointment of the Ewing Commission in 1934-36 to “make enquiry into the condition of the Half-breed population of Alberta.” The association eventually secured land for Métis settlements alongside the passage of the Métis Population Betterment Act in 1938. That same year, the Saskatchewan Métis Society (later the Association of Métis and Non-Status Indians of Saskatchewan) was founded and began to organize for the recognition and protection of Métis rights.

Métis Organizing and the Constitutional Era

In the late 1960s, Métis political activity intensified with the founding of numerous other organizations, such as the Manitoba Métis Federation, the Ontario Métis and Non-Status Indian Association, and the Louis Riel Métis Association of BC. These organizations confronted such issues as the federal government's White Paper of 1969, and the on-going exclusion of Métis and Non-Status Indians from federal policy considerations.

In the 1970s, alongside their Non-Status Indian counterparts, Métis organizations were successful in developing programming that provided social, economic and educational supports for Indigenous peoples. However, due to the federal policy that limited federal funding to Métis and Non-Status Indians, these groups dealt mostly with individual provinces, which in turn considered them to be a federal concern. Nonetheless, Métis and Non-Status Indian organizations developed meaningful partnerships with provincial governments, which have, over the long term, produced an impressive array of social services still in existence today.

During the 1970s, Métis organizations were primarily concerned with social programming for Métis and Non-Status Indians, but during the lead-up to Canadian constitutional patriation, Métis organizations, like their Indian and Inuit counterparts, were increasingly concerned about constitutional protection of their rights and title. During the patriation process, Métis successfully lobbied for inclusion in what became Section 35 of the Constitution Act of 1982, protecting “the existing aboriginal and treaty rights” of Indigenous peoples, who were defined as “Indian, Inuit and Métis.” While Métis (and other Aboriginal) rights and title remained undefined in constitutional practice, Métis did gain a constitutional protection from unjustifiable Canadian infringement on their rights.

Before the constitutional recognition of Métis Aboriginal rights, Métis and Non-Status Indians had worked together out of common interest and necessity. With the Métis recognized as a distinct group in 1982, the alliance began to dissolve. From 1970 to 1983 the Native Council of Canada (NCC, now the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples) represented Métis interests on the national level. However, for the 1983 First Ministers Conference, the Métis National Council was formed to secure Métis representation as a distinct people independent of Non-Status Indians. The First Ministers Conferences of the 1980s, meant to define Section 35 Aboriginal rights, were widely regarded as a failure, and the Métis/Non-Status split became more permanent. Métis organizations began to develop membership codes that reflected Métis-specific membership, excluding many previous Non-Status Indian members. For example, to become a member of the Manitoba Métis Federation, a person must trace their genealogy back to the original Red River Settlement, typically using scrip, parish or census records.

The Courts: Métis Aboriginal Rights

As the recognized Métis “rights and title” of Section 35 were never defined during the First Ministers Conferences, the Métis initiated a series of lawsuits in order for the courts to determine what these rights protected. Since Métis rights were constitutionalized in 1982, three major court decisions have started the long process of defining Métis Aboriginal rights in the Canadian constitutional system, and have highlighted the complexities involved in defining Métis identity.

A transformative movement in Métis rights jurisprudence came in R. v. Powley in 2003. Two Métis hunters, Steve and Roddy Powley shot and killed a moose outside of Sault Ste Marie and were charged with hunting without a licence and unlawful possession of game hunted in contravention of Ontario’s Game and Fish Act. In defence, they claimed that their rights as Métis allowed them to hunt in a manner consistent with their Aboriginal rights, which predated Canadian assertion of sovereignty over their community. As a result, the Supreme Court established the three-part “Powley test” for determining who may claim Métis Aboriginal rights under section 35 of the constitution. A person must: a) self-identify as Métis; b) have an ancestral connection to a historic Métis community; and c) be accepted by a contemporary community that exists in continuity with a historic rights-bearing community.

In 2013, the Supreme Court determined in MMF v. Canada that the government failed in its obligation to properly distribute and safeguard the 1.4 million acres set aside for the Métis in the Manitoba Act. Since this victory, the Manitoba Métis Federation has been lobbying the federal government to enter into a land claims negotiation to compensate the Métis people for lost lands and resources, with the ultimate goal of securing a legally recognized land base for Métis in Manitoba. On 15 November 2016, Indigenous Affairs Minister Carolyn Bennett and president of the Manitoba Métis Federation David Chartrand signed an agreement to bring an end to this 146-year land dispute. Parties must still negotiate the financial settlement for the land as well as some other issues, but this is a step forward in settling the land claim.

Most recently, Daniels v. Canada offered transformative potential for Métis-Canada relations, ending the “jurisdictional wasteland” that stymied relations for generations. In 2016, following a 17-year court battle launched by the late Métis leader Harry Daniels, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that Métis and Non-Status Indians are considered “Indians” under federal jurisdiction as per Section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867. This means that jurisdiction for Métis relations falls to the federal government, rather than the provinces, as has been the common practice for decades. The decision could transform how Métis organizations function, where their funding comes from, the kind of services they are able to offer, and their ability to demand consultation and compensation from the federal government.

Contemporary Life

The blending of European and Indigenous traditions has created a unique and rich Métis culture. In traditional music and dance, Métis fiddling and jigging combine European and Indigenous influences (see Music of the Métis). Métis fiddle music is generally up-tempo and is accompanied by the fast footwork of jiggers. Though there are many fiddle tunes and dances, the most well-known is the Red River Jig, which emerged in the early to mid-1700s. Today, the Métis people still perform traditional music and dances at local and national competitions, community gatherings, powwows and conferences.

Métis art also reflects their unique heritage. Adopting Indigenous beading practices and popular European floral designs, the Métis created an art form all their own. Famous for their floral beadwork, the Métis are often referred to as the “Flower Beadwork People.” Perhaps one of the most famous mainstream beadwork artists is Christi Belcourt, who has been awarded with many national and provincial honours for her work, including the Governor General's Innovation Award (2016), the Ontario Arts Council Aboriginal Arts Award (2014) and Influential Women of Northern Ontario, Aboriginal Leadership Award (2014). The Métis are also well-known for their finger-woven, colourful sashes that have historical, practical and sentimental value.

Like Métis music and art, their language, Michif, is rooted in a mixture of Cree and/or Saulteaux ( Ojibwe) verbs and French nouns. Historically, the Métis could speak various Indigenous languages and were often literate in French or English. Today, many Métis communities speak and teach Michif as a means of keeping the language alive.

A number of influential artists, athletes and politicians have promoted and preserved Métis culture, including writers Sandra Birdsell, Robert Boyer, Maria Campbell and Katherena Vermette; architect Douglas Cardinal; filmmakers, Tantoo Cardinal and Christine Welsh; Ontario Superior Court Justice Todd Ducharme; and professional hockey players René Bourque, Wade Redden, Sheldon Souray and Arron Asham.

According to the 2021 Census completed by Statistics Canada, there are 624,220 people who self-identify as Métis in Canada. This represents a 6.3% increase in the Métis population between 2016 and 2021. Of the 624,220 people who self-identify as Métis, 224,655 claim membership in a Métis organization or settlement.

Landmark Agreements on Métis Rights and Self-Government

On 27 June 2019, the Métis Nation of Alberta (MNA), Métis Nation of Ontario (MNO), and Métis Nation-Saskatchewan (MN-S) signed historic self-government agreements with the Government of Canada. The “Métis-Ottawa Accords” represent a landmark in Métis history, the first self-government agreements between the Métis Nation and the federal government. The historic signing took place in Ottawa between Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Carolyn Bennett, MNA president Audrey Poitras, MNO president Margaret Froh, and MN-S president Glen McCallum.

The agreements are the result of decades of struggle by the Métis people to gain recognition and self-government rights from the federal government. The 2019 accords represent the greatest steps forward for Métis rights since the important hunting, recognition and self-identity rights gained in 2003 (see Powley Case) and 2016 (see Daniels Case). The 2019 accords will be followed by future negotiations that will give the Métis Nation control over its own affairs in areas such as childcare, leadership selection, government operations, and citizenship. Most importantly, the accords give the Métis control over the creation of future constitutions for their various nations.

Carolyn Bennett, speaking on behalf of the federal government, considers the accords the beginning of a new and better relationship between Canada and the three Métis nations involved: “What we’re signing today is a true acknowledgement of the Métis Nation and the relationship we will have going forward — government to government. We’re here to sign not one, not two, but three historic self-government agreements and to recognize that you, the Métis, have control over your own governance.”

Métis Nation of Alberta president Audrey Poitras believes that the accords are a “dramatic shift in attitude for Canada” towards her people and a truly historic moment for the Métis: “It’s not an exaggeration to say the agreements signed today are something we’ve been fighting for for close to a century. Finally, Canada has recognized our right to self-government.”

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom