Nova Scotia is Canada’s second-smallest province (following Prince Edward Island) and is located on the southeastern coast of the country. The province includes Cape Breton, a large island northeast of the mainland. The name Nova Scotia is Latin for “New Scotland,” reflecting the origins of some of the early settlers. Given its proximity to the Atlantic Ocean, Nova Scotia’s economy is largely influenced by the sea, and its harbours have served as military bases during many wars.

Geography

Nova Scotia is part of the Appalachian region, one of Canada seven physiographic regions. The province is primarily a peninsula extending from the country’s mainland. At its northeastern end is Cape Breton Island. Surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, Nova Scotia is separated from Prince Edward Island by the Northumberland Strait and from New Brunswick by the Bay of Fundy.

The Atlantic Upland is one of Nova Scotia’s chief physical features and is recognized by its five fragments, separated in places by extensive lowlands. Of these fragments, the largest is the Southern Upland, which occupies the southern and central part of the province. Starting at the rugged Atlantic coast, and marked by many inlets, islands, coves and bays, it rises to an altitude of 180 to 210 m in the interior. Its northern border constitutes the South Mountain. The second fragment is the North Mountain, a range of trap rock that runs parallel to the South Mountain for 190 km along the Bay of Fundy, from Cape Blomidon, on Minas Basin, to Brier Island.

Between the two mountain ranges lie the fertile valleys of the Annapolis and Cornwallis rivers, which together constitute the well-known apple-growing region of Nova Scotia. The third fragment consists of the flat-topped Cobequid Mountain, rising to 300 m and extending 120 km across Cumberland County, while the fourth has its beginnings in the eastern highlands of Pictou County. It extends in a long narrowing projection through Antigonish County to Cape George. The fifth fragment, on northern Cape Breton Island, is a wild, wooded plateau that peaks to a height of more than 550 m above sea level. It contributes to the scenic character of Cape Breton Highlands National Park, especially as viewed from the Cabot Trail, which runs through it. In contrast, the southern part of Cape Breton Island is largely lowland.

Originally, most of the province was covered by forest, but little of the virgin forest remains, except in the plateau of northeast Cape Breton Island. Secondary growth has tended to be coniferous because of the acid soil and the slow growing season. However, hardwoods continue to exist in sufficient abundance to produce a colourful display in the autumn. In swampy areas and rocky barrens, mosses, lichens, ferns, scrub heath and similar growths are common.

Nova Scotia includes over 3,000 lakes, as well as hundreds of streams and small rivers. Because of the general direction of the watersheds, the rivers are not long. However, with moderately heavy precipitation, normally no shortage of water occurs. The province’s largest lake, the 1,099 km2 Bras D’Or, was created when the sea invaded the area between the upland and lowland areas of Cape Breton. Saline and tideless, it is widely used for recreation. On the peninsula, the largest lake is Lake Rossignol. (See also Geography of Nova Scotia.)

People

Urban Centres

As in the rest of Canada, Nova Scotia has experienced a marked shift from rural to urban living since Confederation. However, its rural population remains relatively high at 30.7 per cent of the total population (2021).

Halifax is both the capital and the largest urban centre in the province. In 2021, it had a population of 465,703, or roughly 48 per cent of the provincial population.

Labour Force

Despite natural resources being the principal driver of the provincial economy, according to the 2021 census, the industries employing the most people were health care and social assistance, retail, and public administration. Going back as far as the mid-1970s, Nova Scotia has consistently had an unemployment rate higher than the national average. In 2021, the unemployment rate was 12.7 per cent (compared to 10.3 per cent nationally), making it among the highest in the country.

Language and Ethnicity

In the 2021 census, the most-reported ethnic origins were Scottish, English and Irish. The visible minority population was relatively small — 9.8 per cent of the total population — with Black, Arab, South Asian and Chinese people making up the four largest communities within this group.

The vast majority of the population (88.8 per cent) reported English as their mother tongue, while those reporting French were 2.9 per cent. The Acadian and francophone populations are concentrated in Halifax, Digby and Yarmouth on the mainland, and in Inverness and Richmond counties on Cape Breton Island. Legislation enacted in 1981 granted Acadians the right to receive education in their first language.

Religion

As in other parts of the country, the population of Nova Scotia is overwhelmingly Christian, with 58.3 per cent of the population identifying with a Christian denomination in 2021. Following Christianity, the most reported religions were Islam (1.5 per cent), Buddhism, (0.3 per cent) and Judaism (0.2 per cent). Those reporting no religious affiliation accounted for 37.6 per cent of the population.

History

Indigenous Peoples

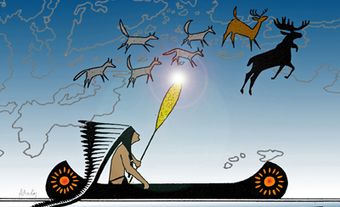

The first peoples in what is now Nova Scotia were the Mi'kmaq, who belonged to a wider coalition known as the Wabanaki Confederacy, whose members were in turn part of the Algonquin-language family in eastern North America. The Mi'kmaq presence can be traced as far back as 10,000 years. They were hunters and traders and, because of their proximity to the ocean, skilled saltwater fishers. When the first Europeans arrived in the 16th and 17th centuries, Mi'kmaq territory stretched across all of modern-day Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, most of New Brunswick and westward into the Gaspé Peninsula of Québec — an area known as Mi'kma'ki. The Mi'kmaq established better relations with the French settlers than with the English.

European Exploration and Settlement

Long before John Cabot made landfall in 1497 (possibly on Cape Breton Island), Norse adventurers may have reached Nova Scotia. Scores of other explorers and fishermen plied its coasts before Pierre Du Gua de Monts and Samuel de Champlain established Port-Royal in 1605 — the first agricultural settlement by Europeans in Canada, and the beginnings of the French colony of Acadia.

In 1621 King James I of England named the same territory New Scotland (or Nova Scotia, as it was called in its Latin charter) and granted the land to the Scottish colonizer Sir William Alexander. In the 1620s, the Scots established two settlements, but both were unsuccessful. Meanwhile a small but steady stream of immigrants continued to arrive from France for a new life in Acadia.

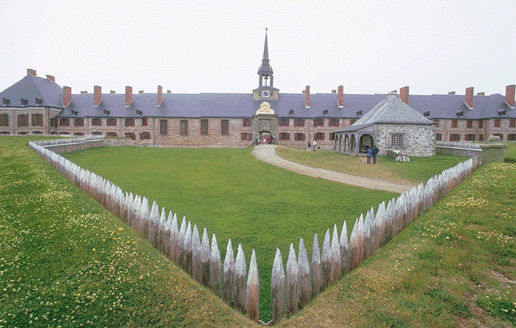

Armed conflict ensued between the French and British, and throughout the 17th century Acadia was handed back and forth between the European powers. The 1713 Treaty of Utrecht finally put an end to Acadia, transferring the colony — but not Île Royale (Cape Breton Island) or Île Saint-Jean (PEI) — to Britain. Aside from maintaining a small garrison at Port Royal, renamed Annapolis Royal, the British did little with Nova Scotia until 1749, when Halifax was founded as a military town and naval base on the shores of what the Mi'kmaq called the "Great Harbour." Halifax's purpose was to balance out the French military presence at the Fortress of Louisbourg in Cape Breton.

The Seven Years War between France and Britain brought great change to Nova Scotia. British military officials feared the colony's large Roman Catholic Acadian population — despite its expressions of neutrality — would side with the French during the war. The result, starting in 1755, was the Acadian Expulsion, in which British forces rounded up more than 6,000 Acadian men, women and children, and dispersed them on ships to various American colonies. In 1758, as these traumatic deportations were still under way, Louisbourg fell to the British, precipitating the Conquest of Canada in 1760, and the ceding to Britain of Cape Breton Island in the Treaty of Paris that ended the war in 1763.

Development

In peacetime, Nova Scotia prospered, with settlers arriving from England, Ireland, Scotland and Germany. Loyalists, both white and black, as well as former black slaves, also arrived following the American Revolution. During the early part of the 19th century the colony grew as a fish exporting, lumbering and shipbuilding centre, and Halifax emerged as an important merchant hub and a base for British privateering captains.

Starting in 1864 the Confederation question left a mark on the province. Nova Scotia's economy was closely tied, as were many families, to the New England states. The province’s prosperity relied on seaborne trade south to the United States and east across the Atlantic, and many did not relish the idea of setting up new economic and political links with the Province of Canada, or with a remote interior further west. Despite these fears the colony became one of the four founding provinces of the new Dominion of Canada in 1867; however, a strong anti-Confederate movement existed for many years, with some Nova Scotians flying flags at half-mast on 1 July.

In the 20th century the First World War stimulated the provincial economy with an increased demand for iron, steel, fish and lumber. The war also brought disaster in the form of the Halifax Explosion; and the war's end brought with it recession, which lasted for several years. Nova Scotia enjoyed good economic times again during the Second World War. Halifax became one of the major North American ports for the gathering of trans-Atlantic convoys, which carried munitions and other wartime supplies to Western Europe.

Since the mid-1950s Nova Scotia has struggled financially, and economic development has been one of the primary concerns for provincial politicians. The fishing industry — especially lobster and shellfish exports — has remained a mainstay of the economy, sustaining many coastal communities even through the collapse of cod and other groundfish stocks in the 1990s.

As manufacturing began its steady decline in the 1950s, coal mining and steel making continued in Cape Breton with the help of massive government subsidies, until the last coal mine was shut down in 2001. Its closure ended a way of life and left the Sydney Tar Ponds — the result of decades of coke oven effluent — as the steel mill's environmental legacy. In an effort to contain the contaminants, the waste was eventually buried, and Open Hearth Park opened on the site of the ponds in 2013.

Coal was also mined on the Nova Scotia mainland starting in the 19th century, and certain strip mining operations continue to this day. The Springhill mine was the site of three deadly disasters, the most famous being the 1958 underground earthquake, which trapped 174 miners and became an international news spectacle.

Offshore oil and natural gas production began in 1992, bringing new revenues and opportunities to the province, but was not the economic windfall many had hoped for. Economic uncertainty continues in the 21st century, with pulp and paper mills across the province closing down and many rural communities in decline as people move to the Halifax area for jobs primarily in government, universities, the burgeoning aerospace sector and the military. Since 2011, great hopes have been pinned on the opportunities that might arise from the awarding of a long-term contract to Irving Shipbuilding to construct 21 new combat ships for the Royal Canadian Navy. It is the largest military procurement in Canadian history.

Economy

Agriculture

While the Mi’kmaq relied on hunting for their food, fishing captains in the early 16th century are believed to have cultivated vegetable gardens to feed their crews. At the same time, the French were growing grain at Port-Royal and in 1609 they erected the first water-powered gristmill in North America. To secure salt for curing fish, they also built dykes along tidal marshes and later used them to begin dykeland agriculture. Since the 1950s, the Department of Agriculture has preserved, extended and rebuilt this system of dykes.

About three per cent of Nova Scotia’s land, or 181,915 ha, is currently used for agriculture. The largest cultivated areas are found in the Annapolis Valley and in some parts of northern Nova Scotia. In 2011, the average farm size was 261 acres, compared to the national average of 778. Gross farm receipts in 2010 were $594.9 million, of which poultry and dairy farms accounted for 46 per cent.

The county fair is an important institution, and the one at Windsor, established in 1765, is the oldest of its type in North America.

Mining

Historically by far the most important mineral in Nova Scotia is coal. The rapid increase in coal production and the development of the steel industry were primarily responsible for the province's prosperity in the early 20th century. After the Second World War conditions in the coal areas were often troubled, and in the late 1950s the market contracted greatly in the face of competition from petroleum and natural gas. Production declined from about 6.6 million tonnes in 1950 to about 2 million in 1971.

Coal made a striking comeback in the 1990s. Following large increases in petroleum prices the province was determined to reduce dependency on foreign oil by replacing it with thermal coal. Production in 1999 amounted to over 1.5 million tonnes worth more than $100 million. While the last Cape Breton coal mine closed in 2001, there are two coal strip mining operations in the province, one in Stellarton and the other Point Aconi.

Other minerals mined in Nova Scotia include gypsum, salt, limestone and sand. (See also Coal Mining.)

Energy

Before 1973 the generation of electric energy was in the hands of the Nova Scotia Power Commission, a government agency established in 1919, and the Nova Scotia Light and Power Company, a private utility. In 1973 they were united in a crown corporation, the Nova Scotia Power Corp. The corporation was privatized in 1992 and is now an incorporated entity.

In 1950 about 70 per cent of the province's energy needs were met by hydroelectric power and indigenous coal. Convinced that cheap oil would continue to be available and that nuclear energy would be less expensive than that derived from coal, governments allowed a situation to develop in which, by 1978, over 70 per cent of the electricity was produced from oil. Nova Scotia had the most expensive energy in Canada because of major increases in oil costs, with the exception of PEI.

In 1979 the Energy Planning Board was established under the new Department of Mines and Energy to devise an energy strategy. This strategy aimed to develop the few remaining hydroelectric opportunities, to open new coal mines and expand existing ones so as to permit oil-fired generating plants to be phased out. As a part of these efforts the Annapolis River tidal plant was completed in 1984. It was the first tidal plant in North America, using the largest turbine ever built for hydroelectric development, and remains the only commercial tidal generating plant in North America Over 30 years later, the strategy to move away from oil-fired generating plants has been successful: in 2012, less than two per cent of the province’s electricity generation came from oil, while 59 per cent came from coal; 21 per cent from natural gas; and 18 per cent from renewable sources such as wind, tidal and hydro. The province’s next challenge is to phase out coal as an energy source, as it is not environmentally or economically sustainable. Nova Scotia is doing this gradually — in previous years the amount of energy produced from coal was as high as 80 per cent.

Offshore drilling for oil and natural gas began in the late 1960s, with the province’s first offshore discovery occurring at Sable Island in 1971. Canada’s first offshore project — Cohasset-Panuke — began production in 1992 (ending in 1999). More discoveries led to the first offshore oil and gas legislation in 1982. In March of that year, Premier John Buchanan signed a 42-year agreement with the federal government giving Nova Scotia the same benefits from its offshore resources that Alberta receives from its land-based oil and gas.

There is currently one offshore project in operation—the Sable Offshore Energy Project—while a second, the Deep Panuke Offshore Gas Development Project, began production in 2013.

Forestry

Nova Scotia has just over 4 million ha of forest, accounting for 79 per cent of its total land area. This resource has always been important in Nova Scotia's economy (see Timber Trade History). In the 19th century, for example, much of the province’s prosperity came from wooden ships and the lumber they carried overseas.

The most common softwood is spruce. Balsam fir is used for pulpwood and Christmas trees. The most important commercial hardwoods are red maple, sugar maple and yellow birch. Sugar maple also forms the basis of an industry for woodlot owners, especially in the north, through the production of maple syrup and allied products.

Fisheries

In terms of landed value (i.e., catch brought ashore), Nova Scotia is a leader among Atlantic coast fisheries. In 2012, for example, it accounted for about 47 per cent ($77 million) of the total landed value of fish caught along the Atlantic Ocean.

Salt and dried fish for export to Latin America was once the staple of the market, but quick-frozen and filleted fish now dominate.

Since the Second World War, schooners with dories have given way to draggers that fish the entire year. More valuable than groundfish such as haddock and cod are molluscs and crustaceans such as scallops and lobsters . The groundfish are caught both by offshore trawlers and draggers, and by inshore boats including long-liners. Lobsters are taken largely inshore by Cape Island boats; scallops by both offshore and inshore draggers; herring by seiners. (See also History of Commercial Fisheries.)

Industry

Manufacturing industries do not have a large presence in Nova Scotia. For example, in 2013, the province accounted for less than two per cent of Canada’s manufacturing sales. What products the province does manufacture, however, are namely food, wood and plastics.

Transportation

In early Nova Scotia the sea was the only highway. In the late 1760s, road building began. Politics in the latter 19th century were focused on the railway, with virtually the province’s entire railway being built between 1854 and 1914.

Due to its ice-free, deep-water harbour located a full day closer to Europe than its major American East Coast competitors, the port of Halifax maintains its competitive edge in the international shipping business. Halifax is one of the largest natural harbours in the world and has one of the largest container ports in Canada.

VIA Rail offers passenger service with stations in Halifax, Amherst, Springhill Junction and Truro. Seagoing car ferries connect southwestern Nova Scotia with New England (via Yarmouth to Bar Harbor, Maine, and via Yarmouth to Portland, Maine) and with New Brunswick (via Digby to Saint John). In addition, car ferries operate from the province to Newfoundland (via North Sydney to Port-aux-Basques, and via North Sydney to Argentia) and to PEI (via Caribou to Wood Islands).

Halifax International Airport, the seventh busiest in Canada and the Atlantic regional hub, enjoys service to major national and international points by major Canadian carriers. Other airports include the Sydney Airport in Cape Breton and Yarmouth International Airport.

Provincial Government

In October 1758 the first legislative assembly in Britain’s North American colonies met in Halifax, and parliamentary government was born in what would become Canada. Yet perhaps Nova Scotia's greatest contribution to Canadian democracy was the movement for Responsible Government, which got underway in earnest in 1836 when — mainly through the efforts of political reformer Joseph Howe and his newspaper The Novascotian — a majority of reform-minded assemblymen was elected to the legislature. Their struggle was against a Halifax oligarchy that dominated the business, political and church life of the province in its own interest, much like the Family Compact in Upper Canada; but what they wanted in practice was for the members of the Executive Council (Cabinet) to be responsible to the elected legislature, not to the appointed colonial governor.

The Reformers finally achieved success when, in the election of 1847, they won a seven-seat majority. In February 1848 James B. Uniacke became premier, with Howe acting as provincial secretary, together forming the first ministry operating under responsible government in British North America. Howe eventually became premier and also a federal Cabinet minister, despite having also led the movement to oppose Nova Scotia's entry into Confederation. (See also Nova Scotia and Confederation.)

Legally, executive power in Nova Scotia is vested in the lieutenant-governor; practically, however, it is exercised by the Executive Council or Cabinet, responsible to a 55-member legislature. Universal suffrage for males and females over 21 came into effect in 1920; the voting age was reduced to 19 in 1970 and to 18 in 1973. (See also Politics in Nova Scotia.)

Health

The Department of Health and Wellness administers an extensive program of family medicine, primary care, dental care, emergency services, mental health services, infection control, continuing care and e-health services. Public health insurance is provided to eligible residents for most hospital and medical services, as well as dental care for children and pharmacare for seniors. Medical and dental research is carried on primarily by the faculties of Medicine and Dentistry at Dalhousie University.

Education

The legislature has always refused to fund faith-based schools, even before Confederation. Education was originally provided via one system that permitted Catholic children to attend separate schools with Catholic teachers, effectively treating the schools as part of the public system, so long as they followed that system's course of study and observed its regulations. With the enlargement of Halifax's boundaries and the consolidation of schools resulting from declining enrolments, the separate system has been substantially impacted.

Of Nova Scotia’s eight school boards, one is a French-language board. The elementary level comprises primary and grades one to six; the secondary level comprises grades seven to nine in junior high, and 10 to 12 in senior high. The public school system is non-denominational.

Post-secondary education consists of independent, degree-granting universities and colleges, the Nova Scotia Community College and private trade schools. Institutions providing regular university programs in Halifax are Dalhousie, Saint Mary’s, Mount Saint Vincent and the University of King’s College; outside Halifax, university programs are at Acadia in Wolfville, St Francis Xavier in Antigonish and Cape Breton University in Sydney. Université Sainte-Anne at Church Point is the only francophone university in the province.

Institutions providing specialized training in Halifax include NSCAD University (formerly the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design) and The Nova Scotia Agricultural College in Truro. Technical education for mariners is provided by the Nova Scotia Nautical Institute and by the Canadian Coast Guard College at Sydney.

The Nova Scotia Community College has 13 campuses around the province, and the Department of Education and Culture operates the provincial apprentice program.

Cultural Life

Arts

Scottish culture is particularly vigorous in the eastern part of the province. St Francis Xavier offers courses in Celtic studies (see Celtic Languages), while the Gaelic College at St Anns, Cape Breton, fosters piping, singing, dancing and handicrafts, and annually hosts the Gaelic Mod, a festival of Highland folk arts. The Antigonish Highland Games, held every summer since the 1860s, are the oldest annual Highland Games in North America. The Halifax Scottish Festival and Highland Games is held annually in Halifax by The Scots: The North British Society.

Since the 1970s, the Nova Scotian government has taken steps to support artistic, and cultural forms and activities. In 1975, it established the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia as an agency of the province responsible for the acquisition, preservation and exhibition of works of art. In 1988 the gallery moved to a restored premise in the historic Dominion Building in downtown Halifax. The Cultural Foundation was established three years later to accept, raise and administer funds for the promotion and encouragement of cultural affairs.

In 1991, the Centre for Craft and Design was established. It is a development centre for crafts- and design-related industries operating in a cultural, educational and economic context. It offers wholesale and retail product information to the trade and provides facilities for learning and display. Visual artists have organized "Studio Rally," an opportunity to visit studios of the province's many visual artists and craftspeople.

Nova Scotia is home to Symphony Nova Scotia, the only professional symphony orchestra east of Québec, and a spate of professional theatre companies, including Halifax's Neptune Theatre and Mermaid Theatre. Annual performing reviews and festivals are successfully attracting tourists and residents alike. These include the popular Cape Breton Summertime Revue, Jazz East, Musique Royale and the Scotia Festival of Music, a weeklong celebration of chamber music held each year in June.

Film production was boosted by the establishment the Nova Scotia Film Development Corp. in 1992. Popular musicians from Nova Scotia include Rita MacNeil, the Rankins, Ashley MacIsaac and the grunge rock band Sloan.

Communications

The newspaper circulating widely throughout the province is the morning Halifax Chronicle-Herald. The daily serving Cape Breton is the Cape Breton Post. There are other dailies in various communities and county weeklies abound.

The CBC provides radio service and there are a large number of private stations. Television is provided primarily by the CBC, CTV and Global.

Heritage Sites

Among Nova Scotia’s many national historic parks are a restored Louisbourg, a replica of Champlain's habitation Port-Royal and the Halifax Citadel.

The provincial government, through the Nova Scotia Museums Complex, has restored a number of structures that are representative of earlier eras, including: Uniacke House, home of Richard John Uniacke, near Halifax; Perkins's House, home of Simeon Perkins, at Liverpool; and "Clifton," home of Thomas Chandler Haliburton, at Windsor.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom