The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples was a Royal Commission established in 1991 in the wake of the Oka Crisis. The commission’s report, the product of extensive research and community consultation, was a broad survey of historical and contemporary relations between Indigenous (Aboriginal) and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada. The report made several recommendations, the majority of which were not fully implemented. However, it is significant for the scope and depth of research, and remains an important document in the study of Indigenous peoples in Canada.

Establishment of the Commission

The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples was established following the Oka Crisis in the summer of 1990. It was part of a package of federal government initiatives in response to concerns arising from the crisis. The terms of reference (the scope of the commission) were developed following consultations conducted by former Chief Justice Brian Dickson with national and regional Indigenous groups, Indigenous leaders in various fields, federal and provincial politicians, and a variety of experts. Upon receipt of Dickson's report, the federal government established the commission by order-in-council on 26 August 1991. The mandate of the commission was to study the evolution of the relationship between Indigenous peoples, the government of Canada and Canadian society as a whole. Sixteen areas were identified for special attention by Justice Dickson.

Members

On the recommendation of Chief Justice Brian Dickson, four of the seven commissioners appointed were Indigenous people; three were non-Indigenous. The co-chairs were Georges Erasmus, a former national chief of the Assembly of First Nations, and Justice René Dussault from the Quebec Appeal Court. Other members included Viola Robinson, former president of the Native Council of Canada(now the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples); Mary Sillett, former president of the national Inuit women's association Paukuutit, and vice-president of the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami; Paul Chartrand, a Métis lawyer and head of the Department of Native Studies at the University of Manitoba; Madame Bertha Wilson, former justice of the Supreme Court of Canada; and Allan Blakeney, former premier of Saskatchewan. When Blakeney resigned in April 1993, he was replaced by Professor Peter Meekison, a political scientist from the University of Alberta and former provincial deputy minister of Federal and Intergovernmental Affairs in Alberta.

Mandate and Consultations

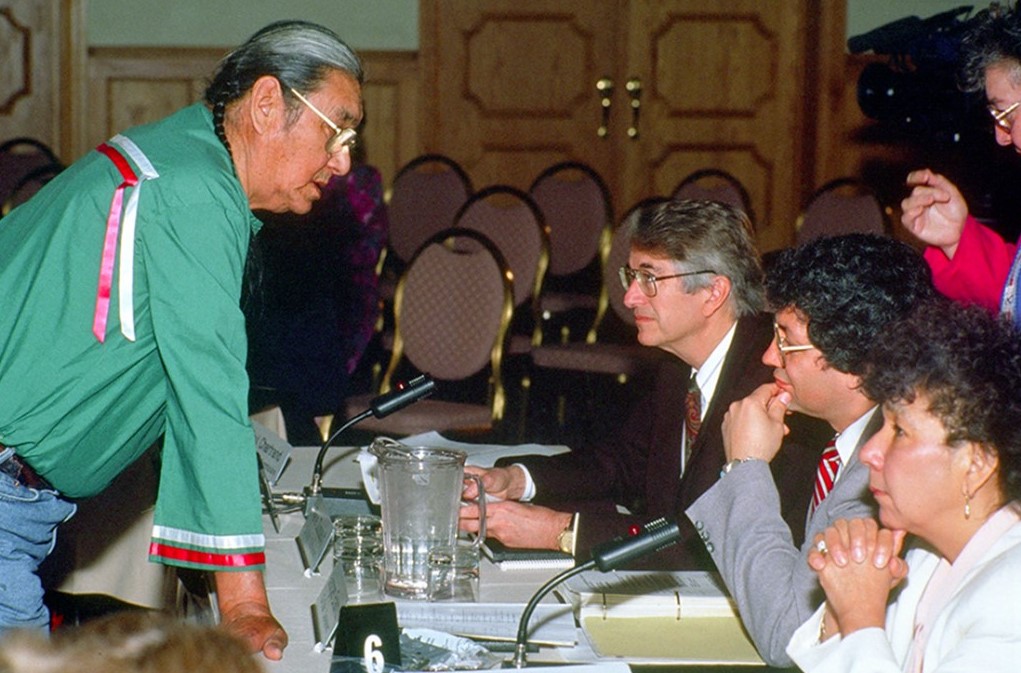

The broad mandate of the Commission was translated into a large and complex research agenda. Consultations were held with Indigenous groups on the development of the research plan. The integrated research plan, which was published in 1993, had four theme areas: governance; land and economy; social and cultural issues; and the North. In addition, these themes were addressed from four perspectives: historical, women, youth and urban. Two co-directors were engaged to manage the research program. In its public hearings process, the commission visited Indigenous communities across Canada and heard briefs from over 2,000 people. More than 350 research studies were commissioned.

The Report and Its Recommendations

The five-volume report was released on 21 November 1996 at a special ceremony in Hull, Quebec. The report included Vol 1: Looking Forward, Looking Back; Vol 2: Restructuring the Relationship(2 parts); Vol 3: Gathering Strength; Vol 4: Perspectives and Realities; and Vol 5: Renewal: A Twenty-Year Commitment.

The main conclusion of the report was the need for a complete restructuring of the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada. Some of the broader recommendations included the proposal for a new Royal Proclamation; which would require the government to commit to a new set of ethical principles respecting the relationship between Indigenous peoples and the state. This new relationship would acknowledge and respect Indigenous cultures and values, the historical origins of Indigenous nationhood and the inherent right to Indigenous self-determination. Implementing many of the recommendations in the Royal Commission would have required constitutional change.

Indigenous Governance

With respect to the theme of Indigenous governance, the commission reviewed a variety of models of self-determination and self-government, and related issues of jurisdiction for each of the three Indigenous groups (First Nations, Inuit and Métis) including those living in urban centres. It recommended that the further development of Indigenous governments should focus on Indigenous nations rather than single communities. It was estimated that there were potentially 60 to 80 Indigenous nations which might be candidates for self-governments throughout Canada. It also called for the establishment of an Indigenous parliament which would be comprised of Indigenous representatives and advise Parliament on matters affecting Indigenous peoples.

Land and Economy

Its recommendations on land and economy emphasized the importance of adequate land and resources, and the need to significantly increase land holdings for First Nations in southern Canada. There was a recommendation for an independent lands and treaties tribunal to oversee negotiations among federal, provincial and Indigenous governments on land issues. Indigenous governments were encouraged to establish economic institutions that reflected cultural values, were accountable and yet were protected from political interference. (See also Indigenous Territory and Economic Conditions of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.)

Social and Cultural Issues

The scope of recommendations on social and cultural issues included the proposed adoption of Indigenous health and healing strategies, an Indigenous peoples international university, educational programs to support Indigenous self-government and public education initiatives to promote cultural sensitivity and understanding among non-Indigenous people. (See also Health of Indigenous Peoples in Canada, Social Conditions of Indigenous Peoples in Canada and Education of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.)

Conclusions and recommendations respecting "the North" focused on the need for ensuring full opportunity for Indigenous peoples to participate in the political and economic development which was already under way. (See also Nunavut and Nunavut and Confederation.)

The report also put forward recommendations for immediate action including the calling of a First Ministers Conference within six months of the report and a major increase in spending on Indigenous programs to the amount of $1.5 to $2 billion a year over 15 years to address pressing health, educational, employment and housing needs. It recommended that a new federal Department of Aboriginal Relations be created to assist Indigenous groups in making the transition to self-government, and that a Department of Indian and Inuit Programs be maintained to provide services to communities which were not ready for change.

Government Response

When the report was released the federal government made a commitment to study it and its recommendations. However, the federal government did not call a First Ministers' Conference within six months of the report's release, as recommended by the commission. Rather, it issued a lengthy information document outlining government achievements from 1993. When the federal government made a formal response on 7 January 1998, its proposals emphasized non-constitutional approaches to selected issues raised by the report. The four objectives of the federal response were renewing partnerships; strengthening Indigenous governance; developing a new fiscal relationship; and supporting strong communities, people and economies. The federal government issued a Statement of Reconciliation in which it expressed profound regret for errors of the past and a commitment to learn from those errors. (See also Reconciliation in Canada.) This was accompanied by a commitment of $350 million to be used to support community-based healing, especially to deal with the legacy of abuse in the residential schools system. Very little response was given by provincial governments, which viewed the report as a federal initiative.

Legacy and Significance

Though federal and provincial governments recognize and support practical initiatives to address social and economic issues included in the report, there has been relatively little government interest in constitutional discussions on issues affecting Indigenous peoples and communities. The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples report provides an Indigenous perspective on Canadian history and the role Indigenous peoples should play in contemporary society. The scope of the recommendations was more far-reaching than any other Royal Commission, including major policy commissions like the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism and the Royal Commission on Economic Union and Development Prospects for Canada. However, because of barriers, or reluctance, to constitutional change, the report's long-term value will be more likely as a major research effort than as a master plan for change.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom