Though often considered Anglo-Canadians, the Scots have always regarded themselves as a separate people. The Scots have immigrated to Canada in steady and substantial numbers for over 200 years, with the connection between Scotland and Canada stretching farther — to the 17th century. Scots have been involved in every aspect of Canada's development as explorers, educators, businessmen, politicians, writers and artists. The Scots are among the first Europeans to establish themselves in Canada and are the fourth largest ethnic group in the country. In the 2021 census, a total of 4,392,200 Canadians, or 12 per cent of the population, listed themselves as being of Scottish origin (single and multiple responses).

The Scots and their descendants shaped place names and institutions, as well as the economic, political and cultural life of the country. Scots have been involved in every aspect of Canada's development. A few of the many well-known Canadians of Scottish descent include Sir Alexander Tilloch Galt, James Bruce (Lord Elgin), Donald Alexander Smith (Lord Strathcona), William Lyon Mackenzie, Harold Adams Innis, Sir William Mackenzie, Sir Hugh Allan, George Stephen, Maxwell Aitken (Lord Beaverbrook), Alexander Begg, William Lewis Morton, Blair Fraser, Norman Bethune, Farley Mowat, Charles William Gordon (pen name Ralph Connor), Douglas Campbell and Norman McLaren.

Migration and Settlement

The Kingdom of Scotland established one of the earliest colonies in Canada in 1621, when Sir William Alexander was granted a charter for Nova Scotia. Alexander established small settlements on Cape Breton Island and at the Bay of Fundy, but they did not flourish, and Scottish claims were surrendered to France in 1632. A few Scots immigrated to New France, but the major early movement of Scots to Canada was a small flow of men from Orkney — beginning around 1720 — recruited by the Hudson’s Bay Company for service in the West. Soldiers from the Highlands of Scotland comprised the crack regiments of the British army that defeated the French in the Seven Years’ War. Many soldiers remained in North America, and Scots merchants moved to Québec after 1759 where they dominated commercial life and the fur trade.

Between 1770 and 1815, some 15,000 Highland Scots came to Canada, settling mainly in Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia (see Hector), and Upper Canada. Most of these immigrants came from the western Highlands or the islands of Scotland. They were almost exclusively Gaelic speaking (see Celtic Languages) and many were Roman Catholic. They congregated in agrarian communities in the new land and, in the early years of the 19th century, Gaelic was the third most common European language spoken in Canada. A few Highlanders were brought to the Red River Colony by the Earl of Selkirk. Other Scots from the fur trade moved with their Aboriginal families to Red River after 1821 (see Métis). In all of these communities, Highland traditions were preserved and for many years they remained distinctive ethnic enclaves.

After 1815, Scottish immigration increased and its pattern altered. Scots from the Lowlands area, encouraged by the British government, joined Highlanders in coming to Canada. Some 170,000 Scots crossed the Atlantic between 1815 and 1870, roughly 14 percent of the total British migration of this period. By the 1850s, most of the newcomers were settling in the Province of Canada rather than in Maritime colonies (see Atlantic Provinces). According to the 1871 census, 157 of every 1,000 Canadians were of Scottish origin, ranging from 4.1 percent of the population in Québec to 33.7 percent in Nova Scotia.

These immigrants represented a cross-section of the Scottish population. Most were farmers and artisans, although large numbers of business and professional people were included, especially teachers and clergymen. Most of the newcomers were Presbyterian and most spoke English. They tended to live and fraternize together and were particularly active in establishing schools (e.g., the St. John's College in Red River, Manitoba) that emphasized training for the talented (see School Systems).

Since 1870, patterns of Scottish immigration and settlement have changed significantly, reflecting shifts in both Scotland and Canada. When population pressures in the Highland region lessened, Highlanders no longer immigrated to Canada in substantial numbers. In the Scottish Lowlands, urbanization and industrialization reduced the agricultural component of the population. The percentage of farmers among immigrants to Canada fell correspondingly.

Meanwhile in Canada, burgeoning manufacturing and cities attracted Scottish immigrants. Still, many made their way to the last great agricultural frontier in Western Canada. The flow of people from Scotland to Canada continued unabated, however. From 1871 to 1901, 80,000 Scots entered Canada seeking a better future, 240,000 arrived in the first years of the 20th century, 200,000 more between 1919 and 1930 and another 147,000 between 1946 and 1960.

Economic and Political Life

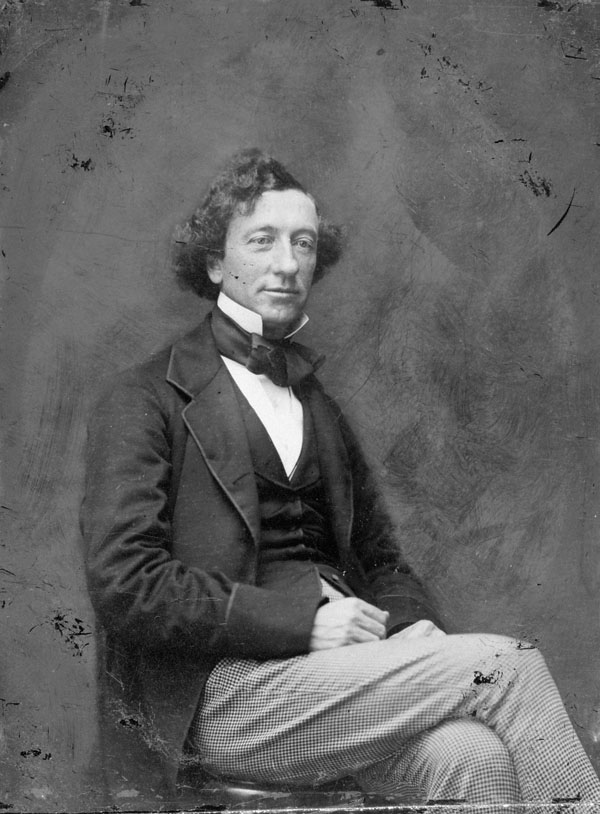

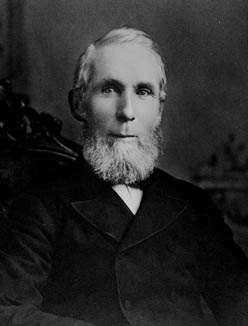

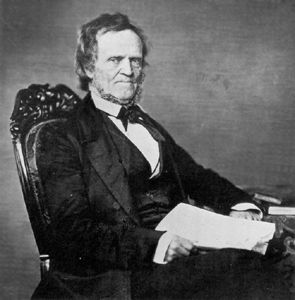

Scots were highly visible in politics and business. Men such as James Glenie and John Neilson often led the criticism of elitist political structures, although other Scots such as John Strachan were members of the elite. The first two Canadian prime ministers — Sir John A. Macdonald and Alexander Mackenzie — were born in Scotland.

Scots were also very active in business. They dominated the fur trade, the timber trade, bankingand railway management. In 1779, Scots businessmen of Montréal (including Simon McTavish, Isaac Todd and James McGill) founded the North West Company (NWC) in order to compete with the Hudson's Bay Company’s (HBC) fur trade monopoly. Quickly, the NWC took two-thirds of the market. The struggle between the two companies at times turned violent, but in 1821, the NWC and HBC merged. Several "lumber kings" who dominated the exploitation and transportation of logs in the Ottawa Valley (see Ottawa River), such as James MacLaren, came from Scotland. The Bank of Montreal (1818) and the Canadian Pacific Railway(1881) are also successful businesses that were created by Scottish businessmen. Nearly 50 per cent of the nation's industrial leaders in the 1880s were of recent Scottish origins.

Education

Success in business generated great fortunes that benefitted the greater community. When merchant James McGill died he left behind his estate and an endowment of £10,000. McGill University was founded by that endowment in 1821. Other Montréal philanthropists of Scottish heritage include Peter Redpath, Lord Stratcona, Sir William Christopher Macdonald, John Molson Jr. and William Molson. McGill University, as many other buildings in Montréal were designed by Scottish architects.

In the Maritimes, the Scots created many educational institutions. This is the case with Dalhousie College in Halifax (later Dalhousie University), founded by George Ramsay in 1818. St. Francis Xavier University in Antigonish was founded by the Catholic Bishop Colin Francis MacKinnon in 1853. In Ontario, Queen's College in Kingston (now Queen's University) was created in 1841 by the Presbyterian Church in collaboration with the Church of Scotland.

It was largely because of their influence that the preponderant culture in Canada was British — rather than English — and that distinctive Scottish patterns can be discerned in Canadian education and moral attitudes, e.g., Sabbath observance and temperance. Scottish moral philosophers strongly influenced philosophical teaching in Canada.

Social and Cultural Life

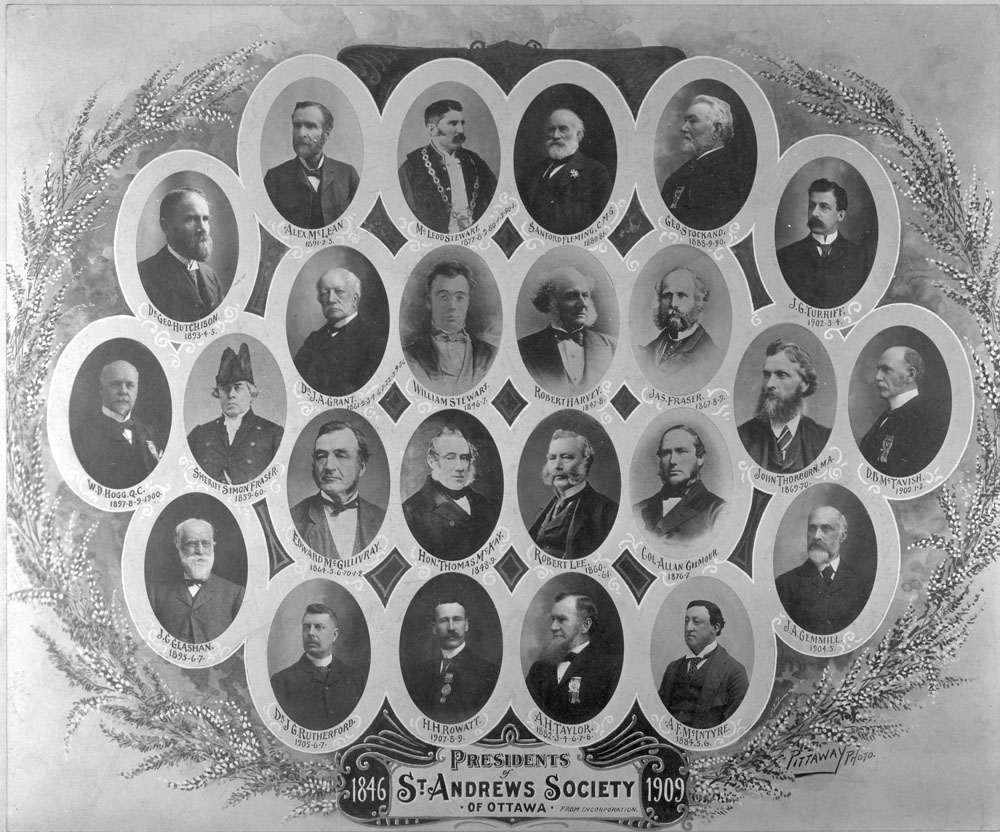

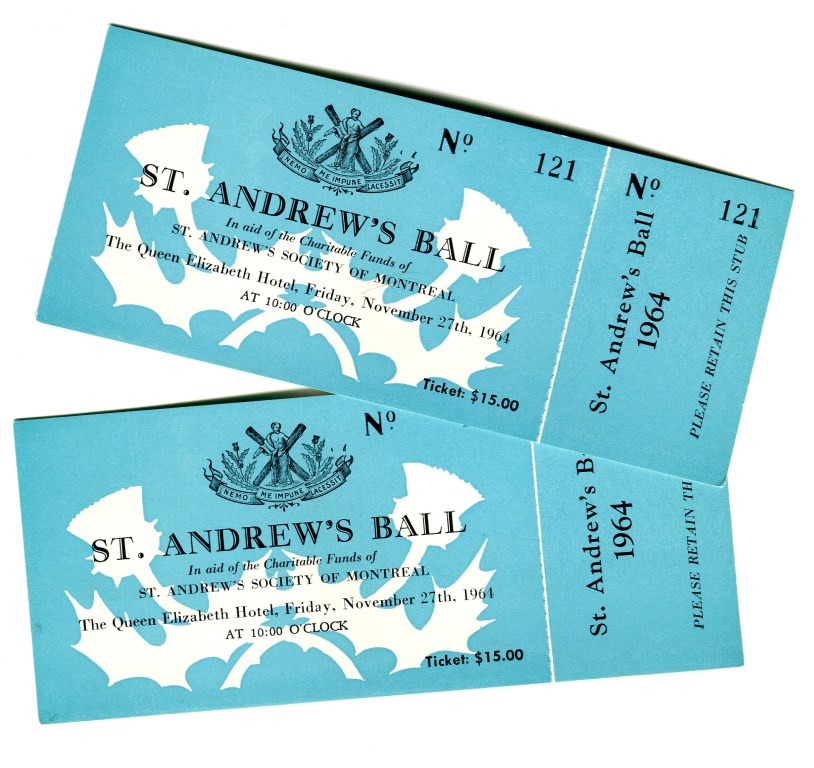

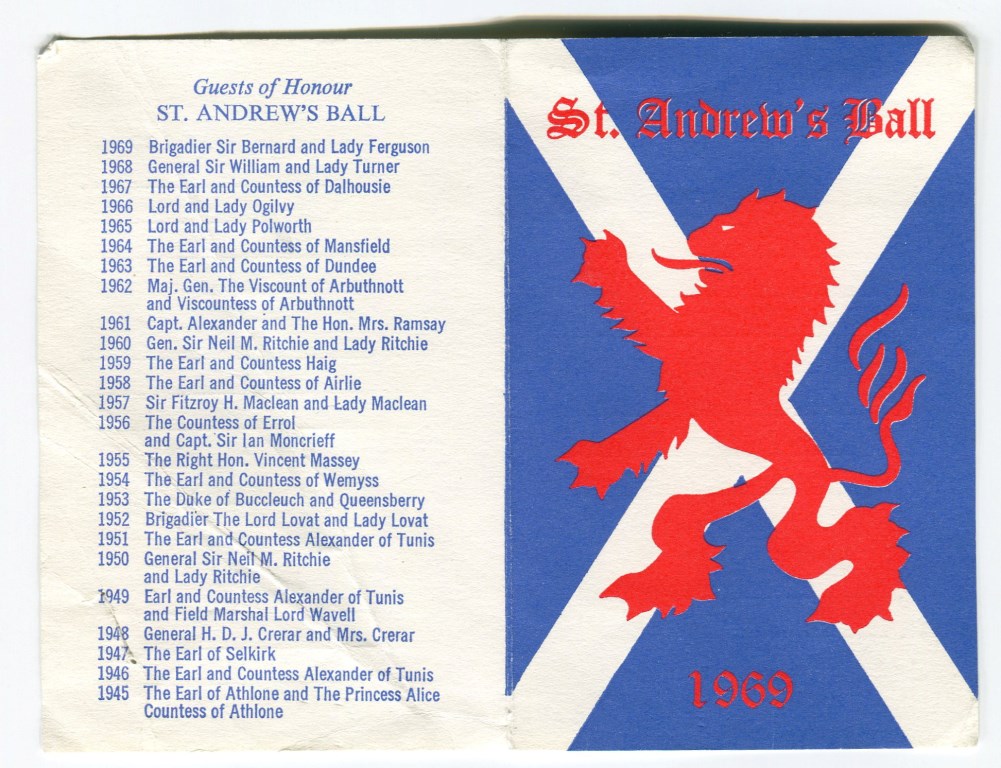

Scots established their own institutions across the country. In Montréal, they created social and sport clubs (Beaver Club, The Royal Montreal Curling Club, Royal Montreal Golf Club), hospitals (Montreal General Hospital), mutual assistance societies and cultural associations (St. Andrew's Society of Montreal) and even an infantry battalion, which became the Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada. The formation of these institutions occurred often very early in the history of Canadian cities. Thus, St. Andrew's and Caledonian Society of Vancouver was founded the same year as the city, in 1886.

Several Canadian place names refer to Scottish culture and personalities of Scottish origin. The word Calgary, of Gaelic origin, means "bay farm" or possibly "Kali's garden," while the Mackenzie River is named in honor of the explorer Sir Alexander Mackenzie, the first European to travel the full length of the river in 1789.

Scottish culture has also captured the imagination of Canadian literature. The stories of the great travelers and explorers of Scottish origin, such as Alexander Henry and Mackenzie, are the subject of numerous re-editions (see Exploration Literature). In the early 20th century, Ralph Connor (Charles William Gordon), a pastor of Glengarry County in Ontario was the most widely read Canadian author. His novels (including Glengarry School Days) sold more than 5 million copies. The Scotch (1964) written by economist John Kenneth Galbraith is an entertaining account of his boyhood environment in a small Scottish community in Elgin County. The father of Canadian Animation, Norman McLaren is also of Scottish origin.

Cultural Conservation

Like most immigrant groups, the Scots have shunned the Atlantic region and Québec since 1870, moving instead to Ontario and the West. A substantial population of Scottish origin in the Maritime Provinces is Canadian-born. Newfoundland, like Québec, has never had a significant Scottish population. Scots are widely distributed across the remaining provinces and territories in both urban and rural communities.

Like most ethnic groups in Canada, the Scots have become increasingly assimilated into Canadian society, although still retaining an awareness of their distinctive heritage. Like other ethnic groups as well, the Scots have tended to focus on a few highly visible symbols of their origins, such as clans, tartans, Highland dancing and curling. Since 1819, the Highland Games are held in various Scottish communities in Canada. This tradition, where sport competition, dance and music come together, now forms an integral part of Canadian culture. In Montréal, the St. Andrew Society organizes annual balls, dinners and public lectures to celebrate the Scottish heritage of the city. The Society also presents Whisky-Fête, a fundraiser to support and create a Chair in Canadian-Scottish Studies at McGill University. Finally, on 25 January, Canadians of Scottish descent gather to celebrate the birth of Scottish poet Robert Burns (1759–1796), the author of the famous unofficial Scots anthem, "Scots Wha Hae". Called "Robbie Burns Day", it is an opportunity to hear the bagpipes, see Scotsmen in kilts and eat the Scottish national dish, haggis.

The number of Gaelic speakers has declined in Canada as it has in Scotland. A few thousand people, mainly in Cape Breton, keep the language alive in Canada. However, the Nova Scotia Office of Gaelic Affairs estimated in 2007 that there were 2,000 Nova Scotians who spoke Scottish Gaelic. Proud of this heritage, the Nova Scotia government has implemented various measures to promote and preserve the language. In 1997, the Ministry of Education developed a curriculum centered on Gaelic culture for high schools. Bilingual road signs (in English and Gaelic) were also developed and implemented in 2006 at the initiative of the Ministry of Transport and Public Works in the localities of the province where the Gaelic tradition is still alive.

The history and culture of Scots developed quite differently from that of other groups from the British Isles — the English, Welsh and Irish. Their pattern of immigration to and development in Canada is unlike that of most other ethnic peoples, for it has been protracted over several centuries rather than being chronologically or regionally specific. Scots have never been sufficiently numerous to dominate, nor sufficiently lacking in numbers to vanish.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom