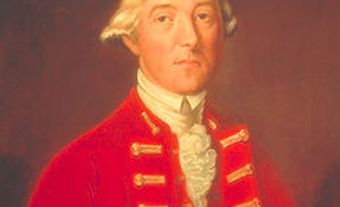

Sir Charles Bagot, diplomat (born 23 Sept 1781 at Blithfield Hall, England; died 19 May 1843 in Kingston, Canada). Born to a wealthy and influential family, Bagot was elected to the British Parliament in 1807. He served in the cabinet as undersecretary of state for foreign affairs before appointments as Britain’s minister to France (1814), the United States (1816-19), Russia (1820-24), and the Netherlands (1824-32). As Britain’s minister to the United States, he negotiated the 1817 Rush-Bagot Agreement which reduced the number of military ships on the Great Lakes and Lake Champlain and helped secure the Canadian-American border. From 1841-43, he served as Governor General of the Province of Canada, advancing responsible government and French-English equality in the colony.

Early Life

Bagot was born to an aristocratic family at its estate, Blithfield Hall, 8 km north of Rugeley, England. His mother was the daughter of 2nd Viscount St. John, and his father was long-serving member of parliament William Bagot, 1st Baron Bagot. He attended the prestigious Rugby School and, in 1804, earned a master’s degree from Oxford University.

Bagot married Mary Charlotte Anne Wellesley-Pole whose father was the 3rd Earl of Mornington and whose uncle was the Duke of Wellington. They had several children together.

Bagot’s uncle arranged for him to win a seat in parliament in 1807, representing Castle Rising. He was appointed under-secretary of foreign affairs. Bagot left politics after one term to seek diplomatic postings.

Early Diplomatic Career

In 1814, Bagot was appointed minister plenipotentiary to France, a position with many of the same powers and privileges as ambassador. He was a hard-working and highly skilled negotiator who honourably represented Britain and its interests.

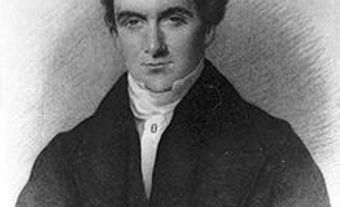

In July 1815, the 34-year-old Bagot was appointed minister plenipotentiary to the United States. The War of 1812, that had seen violence and destruction on both sides of the American-Canadian border, ended with the ratification of the Treaty of Ghent in February 1815. Tensions between Britain and the United States nonetheless remained high. Bagot negotiated with American secretary of state James Monroe and then his successor, Acting Secretary Richard Rush. The Rush-Bagot Agreement (or Rush-Bagot Treaty) was ratified by the American Senate on 28 April 1818. It set a limit on the size and number of military ships on the Great Lakes and Lake Champlain. The treaty eased border tensions, allowed Britain and the United States to reduce military spending, and allowed more trade through the lakes.

In June 1820, Bagot was appointed ambassador extraordinary to Russia. Bagot negotiated a deal that helped British trade by having the Russian government reverse an earlier edict that banned all but Russian ships in the north Pacific.

Bagot was appointed Britain’s ambassador to the Netherlands in November 1824. He was influential in negotiations that eventually led to Belgium’s independence in 1831.

Bagot returned to private life in 1832. In 1835, he served briefly as Britain’s special representative in Austria where he supported Prince Ferdinand in becoming the new Austrian monarch. Bagot again returned to private life.

Governor General of Canada

Bagot was 60 years old in 1841 when British Colonial Secretary Lord Stanley asked him to accept the position of Governor General of the Canadian colony. Bagot arrived in Kingston in January 1842. It would be a tough assignment because of the problems and tensions within the political system there.

Canada’s government had been re-structured following the 1837 Rebellions, according to the recommendations of the 1839 Durham Report. The colonies of Canada East (Quebec) and Canada West (Ontario) were united into one colony in 1841, called Canada, with its capital in Kingston. The new government was to be responsible to the people, rather than the British crown. The members of the executive council (like today’s cabinet) were to be chosen by the legislative assembly (like today’s House of Commons). The government retained power only with the support of the legislative assembly. The new government structure was also meant to allow the growing English majority to slowly overwhelm and eliminate the French presence in Canada.

Britain sent Governor Lord Sydenham to enact parts of the Durham Report. He unified the two colonies into one and kept French leaders from positions of power. As instructed by the British government, he did not implement responsible government. He was supported in his efforts by members of the Tory Party. French and English Canadian members of the Reform Party, meanwhile, attempted to elect more of their members to force the executive council to be responsible to the legislative assembly, and therefore to the people. By late 1841, the colony was divided, and its government appeared about to collapse.

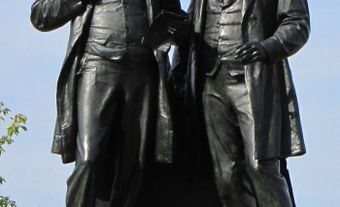

Bagot, who arrived in early 1842, spoke French and he and his wife were frequent and welcome guests at English and French official parties and events. Bagot asked influential French and Reform Party members to join the executive council, including important French Canada East leader, Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine. Lafontaine insisted on forming a political partnership with Canada West’s Reform leader Robert Baldwin. Bagot and Lafontaine bargained for several days until they agreed on the French and Reform members who would be invited to join the executive council. A majority in the legislative assembly supported the new Baldwin and Lafontaine government. (See The Politics of Cultural Accommodation: Baldwin, LaFontaine and Responsible Government.)

Tories were upset by Bagot’s compromise. Reformers, however, saw the Baldwin-Lafontaine government as an important step in recognizing the rights and permanence of the French in Canada and in the creation of responsible government. Bagot reported to London, “whether the doctrine of responsible government is openly acknowledged, or is only tacitly acquiesced in, virtually it exists.”

While governor general, Bagot was appointed the ex officio chancellor of Toronto’s new King’s College, that would later become the University of Toronto. He was influential in hiring professors and, in 1842, he officiated at its opening.

Bagot’s Death

In the fall of 1842, Bagot fell ill. He was forced to resign in January 1843. His successor took over his office on 30 March 1843, and Bagot died on 19 May of that year.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom