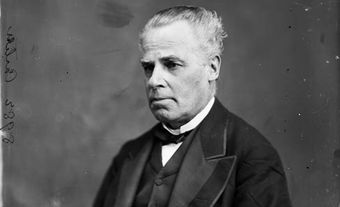

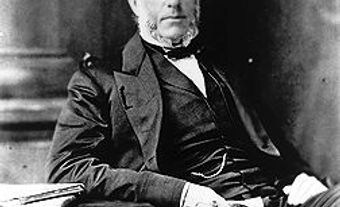

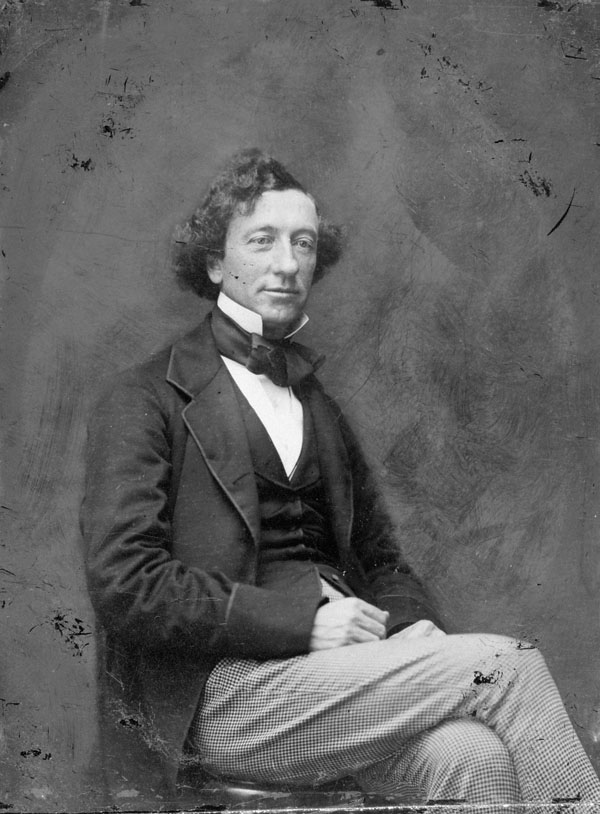

Sir John Alexander Macdonald, prime minister of Canada 1867–73 and 1878–91, lawyer, businessman, politician (born 10 or 11 January 1815 in Glasgow, Scotland; died 6 June 1891 in Ottawa, ON). John A. Macdonald was Canada’s first and second-longest serving prime minister (19 years). He set wide-ranging policies that continue to influence the country today. Macdonald helped unite the British North American colonies in Confederation and was a key figure in the writing of the British North America Act — the foundation of Canada’s Constitution. He oversaw the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) and the addition of Manitoba, the North-West Territories, British Columbia and Prince Edward Island to Confederation. However, his legacy also includes the creation of the residential school system for Indigenous children, the policies that contributed to the starvation of Plains Indigenous peoples, and the “head tax” on Chinese immigrants.

Early Life and Education

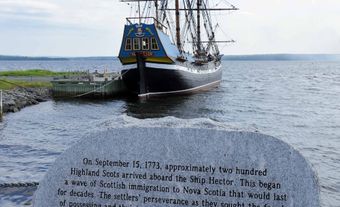

Macdonald and his parents, Hugh and Helen (née Shaw) Macdonald, immigrated to Kingston, Upper Canada, from Scotland when he was five years old. (See also Scottish Canadians.) His father opened a series of businesses in the area. Macdonald grew up in Kingston and in the nearby Lennox, Addington and Prince Edward counties. He attended the Midland District Grammar School. He then went to a private school in Kingston, where he was educated in rhetoric, Latin, Greek, grammar, arithmetic and geography.

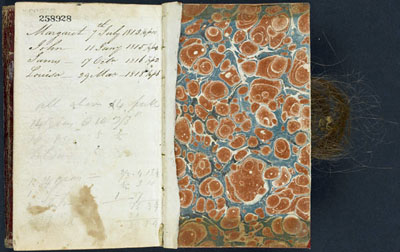

DID YOU KNOW?

The exact date of John A. Macdonald’s birth remains a mystery. His father’s journal lists 11 January 1815 as Macdonald’s birthdate; it also suggests his family celebrated his birthday on that day. But a certified extract from the registration of his birth cites 10 January.

Early Career

At age 15, Macdonald began to article with a prominent Kingston lawyer. He showed promise both at school and as an articling student. At 17, he managed a branch legal office in Napanee by himself. At 19, he opened his own office in Kingston. Two years later, he was called to the Law Society of Upper Canada.

Macdonald’s early professional career coincided with the rebellion in Upper Canada and the resulting border raids from the United States. He was in Toronto in December 1837; as a militia private, he took part in the attack on the rebels at Montgomery’s Tavern. In 1838, he attracted public notice by defending accused rebels, including Nils von Schoultz, the leader of an attack on Prescott. (See Battle of the Windmill.)

Legal Career and Business Interests

Macdonald practiced law for the rest of his life with a series of partners; first in Kingston (until 1874) and then in Toronto. His firm engaged primarily in commercial law; his most valued clients were established businessmen or corporations. He was also personally involved in a variety of business concerns. He began to deal in real estate in the 1840s. He acquired land in many parts of the province, including commercial rental property in downtown Toronto. He was also appointed director of many companies, most of them in Kingston. For 25 years (including his years as prime minister), he was president of the St. Lawrence Warehouse, Dock and Wharfage Co., a firm in Quebec City. In 1887, he became the first president of the Manufacturers Life Insurance Co. of Toronto (now Manulife Financial Corporation).

Entry into Politics

Macdonald entered politics at the municipal level. He served as alderman in Kingston from 1843 to 1846. He took an increasingly active part in Conservative politics. In 1844, at age 29, he was elected to the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada. Parties and government were in a state of transition. A modern departmental structure had begun to evolve; but the British government had not yet agreed to responsible government in British North America, and the role of governor general was still prominent.

In 1847, Macdonald was appointed to cabinet as receiver general in the administration of W.H. Draper. However, Draper’s administration was defeated in the general election that year.

Macdonald remained in Opposition until the election of 1854. He was then involved in the creation of a new political alliance — the Liberal-Conservative Party. This new party brought together the Conservatives with an already existing alliance between Upper Canadian Reformers and the French Canadian majority bloc, the Parti bleu.

Premier of the Province of Canada

Back in office, Macdonald assumed the prestigious post of attorney general of Canada West (formerly Upper Canada). When Conservative leader Sir Allan MacNab retired in 1856 — an event Macdonald helped engineer — Macdonald succeeded him as joint-premier of the Province of Canada; first with Étienne-Paschal Taché, then with George-Étienne Cartier (1857–62).

Macdonald and Confederation

During the years 1854–64, Macdonald faced growing opposition in Canada West to the political union with Canada East (formerly Lower Canada). In 1841, the Province of Canada had been created, uniting the two colonies under one parliament. (See Act of Union.) The Reform view, voiced by George Brown of the Toronto Globe, complained that the needs and goals of Canada West were frustrated by the “domination” of French Canadian influence in the government of Macdonald and Sir George-Étienne Cartier.

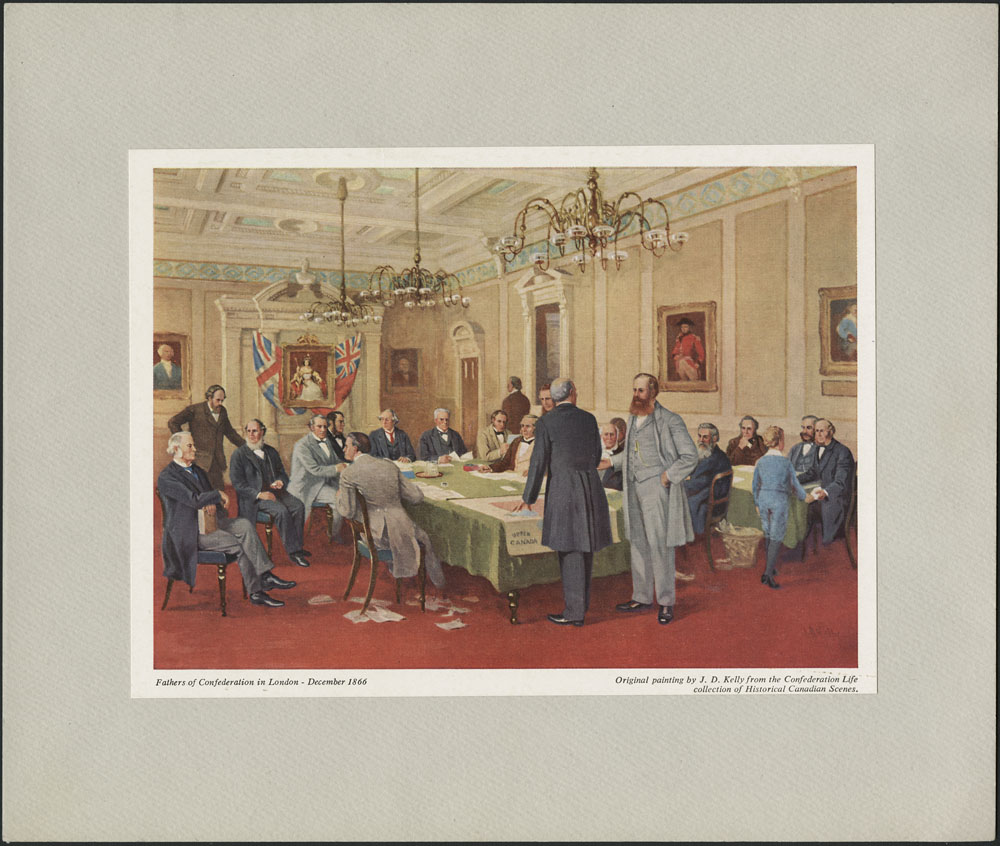

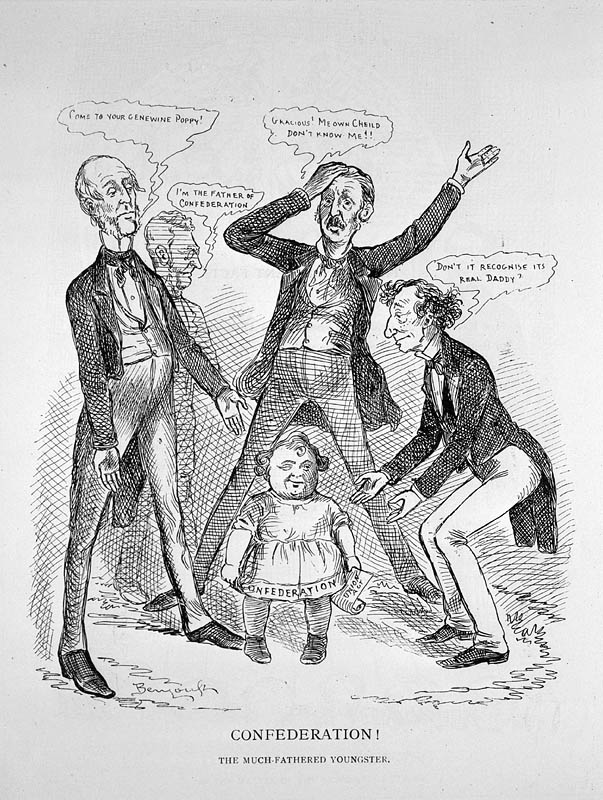

By 1864, the political and sectional forces in the province were deadlocked. Macdonald reluctantly accepted Brown’s proposal for a new coalition of Conservatives, Clear Grits, and Bleus. (See Great Coalition of 1864.) They would work together for constitutional change. (See Charlottetown Conference; Quebec Conference; Quebec Resolutions.) Macdonald and the coalition played a key role in uniting the former British North American colonies — the new provinces of Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia — into Confederation in 1867.

DID YOU KNOW?

No Indigenous peoples were invited to participate in the discussions that resulted in Confederation. In spite of this, the British North America Act gave the federal government exclusive responsibility for “Indians, and Lands reserved for the Indians.” This made Indigenous people wards of the state and created a dynamic in which the government treats Indigenous people paternalistically; not as equal, but as “children of the state” who have not yet earned the right to enter “civilized” society.

Macdonald conceded that a federation was necessary to accommodate the strong racial, religious and regional differences in the new country. His preference was for a strong, highly centralized, unitary form of government. Macdonald took a leading role in drafting the federal system. He ensured that the central government held unmistakable dominance over the provincial governments. ( See Distribution of Powers.) His constitutional expertise, ability and knowledge were quickly recognized by the imperial government. Lord Monck, former Governor General of the Province of Canada and the first Governor General of the Dominion, appointed Macdonald as the first prime minister of Canada on 1 July 1867. Macdonald was also knighted (Knight Commander of the Bath), becoming Sir John A. Macdonald.

Nation Builder

During Macdonald’s first administration (1867–73), the new country expanded dramatically. The original four provinces of Confederation were joined by Manitoba (1870); the North-West Territories (1870; present-day Alberta and Saskatchewan); British Columbia (1871); and Prince Edward Island (1873). The Intercolonial Railway between Quebec City and Halifax was begun. Plans were also made for a transcontinental railway to the Pacific Coast.

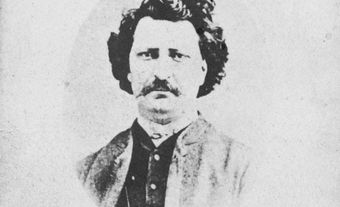

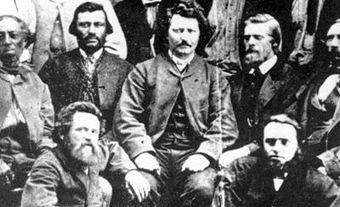

These undertakings involved the unprecedented spending of public funds and did not proceed without conflict. Manitoba entered the union following an armed resistance by Louis Riel and the Métis against the takeover of the area by Macdonald’s government. (See Red River Resistance.) As a result, Manitoba was granted provincial status much sooner than had been intended; it also mandated a system of separate schools and the equality of the French and English languages. (See Manitoba Act; Manitoba Schools Question.)

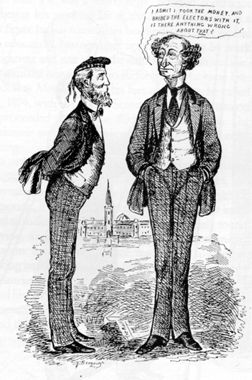

Pacific Scandal

Macdonald’s involvement in the negotiations for a contract to build the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) to British Columbia formed the heart of the Pacific Scandal. Macdonald and senior members of his Conservative cabinet accepted large campaign contributions for the 1872 election from shipping magnate Sir Hugh Allan; in exchange, Allan received the contract to build the CPR. (See also Political Corruption.) Macdonald claimed that his “hands were clean” because he had not profited personally from his deal with Allan. But he was forced to resign in late 1873. In the election of 1874, his government was defeated.

Return to Power

Macdonald’s defeat in 1874 coincided with the onset of a depression in Canada. This made the Liberal government of Alexander Mackenzie appear ineffective. In 1876, at the urging of a group of Montreal manufacturers, Macdonald began to advocate a policy of “readjustment” of the tariff. This policy helped him return to power in 1878. He remained prime minister until his death on 6 June 1891.

National Policy

The promised changes in tariff policy were introduced in 1879. They were frequently revised in close collaboration with leading manufacturers. This formed the basis for Macdonald’s National Policy. It was a system that protected Canadian manufacturing by imposing high tariffs on foreign imports, especially from the United States. (See Protectionism.) The National Policy appealed to Canadian nationalist and anti-American sentiments. It became a permanent feature of Canadian economic and political life. However, the economy continued to suffer slow growth, and the effects of the policy were uneven.

Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) and Western Settlement

The great national project of Macdonald’s second administration was the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR). It was a difficult and expensive undertaking that required vast government financing. Macdonald played a central role in making the railway a reality. He was involved in awarding the contract to a new syndicate headed by George Stephen. The contract called for a government subsidy of $25 million and 25 million acres (10 million hectares) of land. On two occasions, in 1884 and 1885, Macdonald introduced legislation to give the railway more funding. Its completion in November 1885 made possible the future settlement of the West. (See also Railway History in Canada; Railway History Timeline.)

To Macdonald, the building of the CPR took priority over almost everything else. The railway would be the backbone of the country, connecting all the disparate regions in harmonious prosperity and warding off the threat of American annexation. Macdonald had initially wanted to send a paramilitary force to secure Canadian sovereignty in the West and prepare the way for settlement. Instead, his government created the North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) to assert federal authority in the West.

To ensure the railway’s completion across the Prairies, Macdonald made himself the superintendent general of Indian Affairs. In this role, he could direct the activities of Indian Agents. They were responsible for enforcing and administering government policy. According to historian James Daschuk, Canadian officials in the 1880s withheld food from Indigenous people until they moved to reserves, thus clearing the land needed for railway construction. This, combined with the scarcity of bison at the time, led to the deaths of thousands of Plains Indigenous people.

Canada’s Growing Autonomy

The physical linking of Canada’s vast geography was accompanied by the first steps toward autonomy in world affairs. Macdonald did not foresee Canadian independence; he sought a partnership with Britain. Yet during his time in office, Canada moved closer to independence. Macdonald himself represented Canada on the British commission that negotiated the Treaty of Washington of 1871. In 1880, the post of Canadian high commissioner to Britain was created. In 1887, Finance Minister Charles Tupper represented Canada at the Joint High Commission in Washington.

Later Years

The last stage of Macdonald’s public career was filled with controversies and crises. The North-West Resistance occurred when Macdonald was superintendent general of Indian Affairs. The subsequent execution of Louis Riel in 1885 greatly increased animosity between French-speaking and English-speaking Canadians. It also cost Macdonald political support in Quebec, where Riel was seen as a martyr to the forces of Anglo-Saxon imperialism.

In addition, Ontario premier Oliver Mowat launched a series of successful legal challenges to the powers of the federal government. As a result, the federal system became much less centralized than Macdonald had intended. For example, the federal power of disallowance had been freely used during the early days of the Dominion; it enabled the federal Cabinet to cancel provincial legislation. But it was virtually abandoned by the end of the 19th century, due to provincial opposition.

Indigenous Peoples

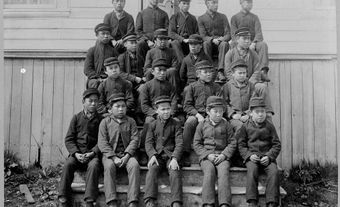

As both prime minister and superintendent general of Indian Affairs, Macdonald was responsible for the federal government’s policies toward Indigenous peoples. This included the implementation of residential schools as a federal program in 1883; as well as increasingly repressive measures against Indigenous peoples in the West.

Macdonald’s government intended to assimilate Indigenous peoples into Canadian society. It tried to do so with the passage of the British North America Act (now called the Constitution Act, 1867) in 1867 and the Indian Act in 1876. Macdonald and his government established the residential school system as a federal program to be run in conjunction with the Catholic and Protestant churches. He argued that assimilating Indigenous peoples into settler, Christian society could only be achieved through residential schools. On 9 May 1883, he told the House of Commons, “When the school is on the reserve the child lives with its parents who are savages; he is surrounded by savages… He is simply a savage who can read and write.”

Macdonald introduced other assimilationist policies affecting Indigenous people, including the pass system, which controlled the movement of Indigenous people; as well as the criminalization of powwows and potlatches.

Macdonald also tried to extend the federal vote to all Indigenous males, so long as they met the same conditions as other British subjects. Under his proposal, they would not have to give up Indian status to vote (as was the case under previous legislation). Macdonald’s proposal was controversial, and the final Electoral Franchise Act of 1885 was a compromise. The Act extended the vote to Indigenous men who lived on reserves if they owned land and had made at least $150 worth of improvements to their property. However, it excluded all Indigenous men in the West — likely in reaction to the North-West Resistance of 1885. In 1898, the legislation was repealed, and many Indigenous men were again disqualified.

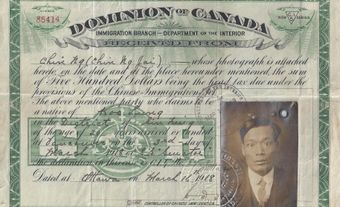

Chinese Immigration

While Macdonald proposed extending the right to vote to all Indigenous males, he also passed legislation to exclude those of Chinese origin from voting. In the 1880s, around 15,000 Chinese labourers helped build the Canadian Pacific Railway. Working in harsh conditions for little pay, they suffered greatly. Historians estimate that at least 600 died. Their employment had caused controversy, particularly in British Columbia; politicians there worried about the potential economic and cultural impact of this influx of Chinese workers. Macdonald, however, defended their employment in constructing the railway, saying, “it is simply a question of alternatives; either you must have this labour or you can’t have the railway.”

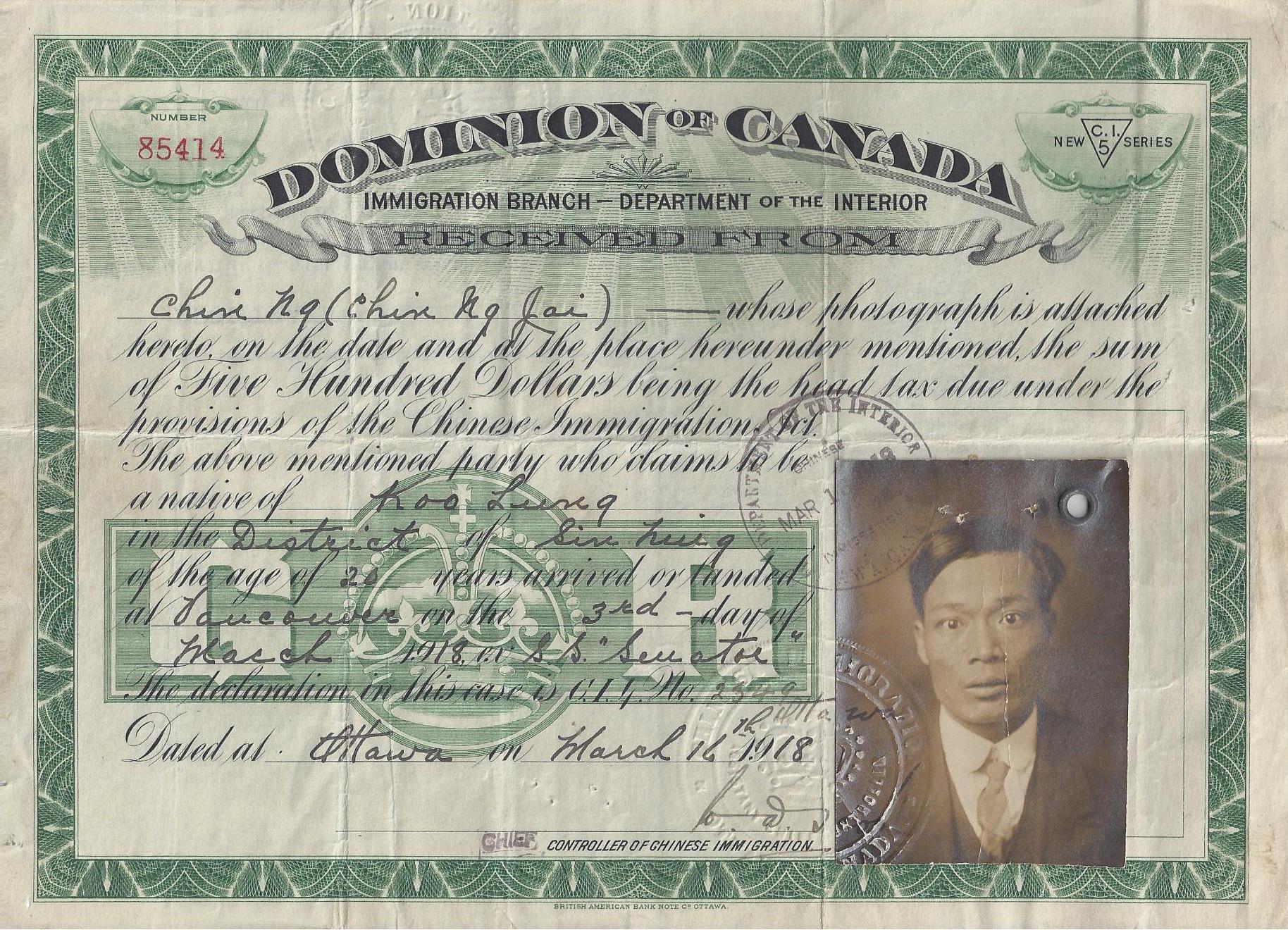

But as the project neared completion, Macdonald and the federal government excluded “persons of Mongolian or Chinese race” from voting. This was done on the grounds that they had “no British instincts or British feelings or aspirations” (Electoral Franchise Act, 1885). That same year, Macdonald’s government passed the Chinese Immigration Act (1885). It required that anyone of Chinese origin pay a “head tax” of $50 to enter the country.

Macdonald’s policies and his personal views of Chinese immigration have been widely debated. Some have accused him of racism, discrimination, and white supremacy. During a debate in the House of Commons on 4 May 1885, Macdonald said, “the Aryan races will not wholesomely amalgamate with the Africans and Asiatics. It is not to be desired that they should come; that we should have a mongrel race; that the Aryan character of the future of British America should be destroyed by a cross or crosses of that kind….”

However, others have argued that Macdonald was progressive by Victorian standards. Richard Gwyn has noted that Macdonald was criticized in his day for being too moderate. The United States, in comparison, had banned all Chinese immigration in 1882. And the Canadian government under Liberal leader Sir Wilfrid Laurier soon increased the Chinese head tax to $500 in 1903. Macdonald even proposed giving women the right to vote in 1885, more than 30 years before they officially received it.

Personal Life

Macdonald’s personal life was marked by misfortune. His first wife, his cousin Isabella Clark, suffered from an undiagnosed illness. She died in 1857. Their first son, John Alexander, died at the age of 13 months; a second son, Hugh John (born in 1850), survived.

In 1867, Macdonald married Susan Agnes Bernard. She gave birth in 1869 to a daughter, Mary. Mary was born with hydrocephalus (excess fluid in the brain) and never walked. She was never institutionalized and lived until 1933. She and her father were reportedly very close.

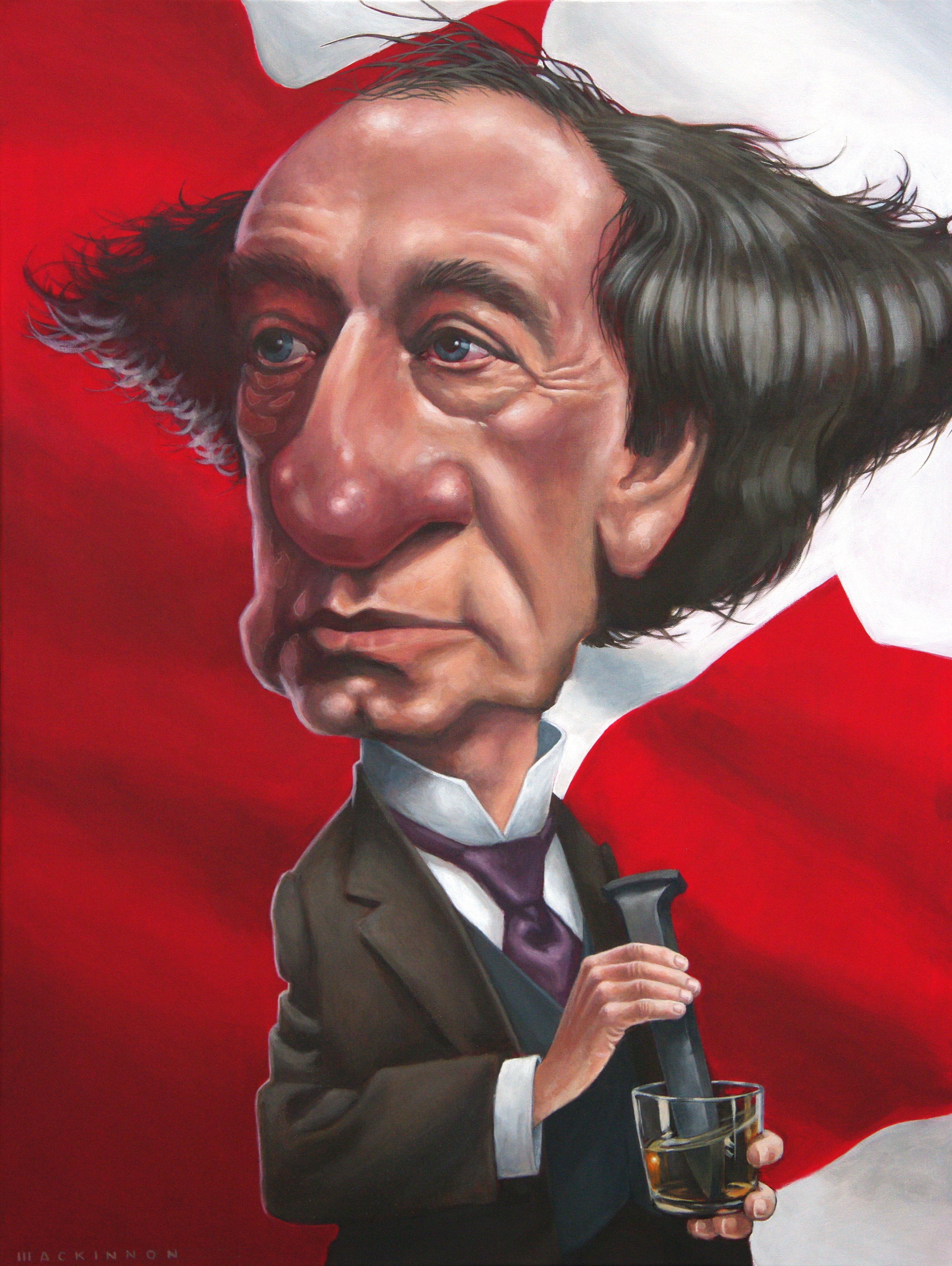

Some of Macdonald’s political problems stemmed from his heavy alcohol consumption. In 1866, when he was minister of militia and defence for Canada West, his drinking problem posed a national security risk; he was allegedly too drunk to respond to multiple telegrams warning of the Fenian raids. Also, Macdonald could not recall periods of time during the 1872 election and the negotiations with Sir Hugh Allan that formed the basis of the Pacific Scandal, which led to his resignation as prime minister. In March 1875, Macdonald joined the Church of England to try and discipline his drinking. In his later years, he came to favour milk over liquor.

Legacy

Macdonald’s contribution to the development of the Canadian nation exceeded that of any of his contemporaries. He was not by nature an innovator; Confederation, the CPR, and the protective tariff were not his ideas. But he was brilliant and tenacious in achieving his goals, once convinced of their necessity.

Macdonald was a highly partisan politician; in part, because he genuinely believed it was essential to maintain certain political courses. He was especially concerned with maintaining Canada’s connection to Britain — including the tradition of parliamentary supremacy — against the threat of American economic and political influences; such as the doctrine of constitutional supremacy. (See also Constitutional History of Canada.)

Macdonald was an Anglophile, but he also became a Canadian nationalist. He had great faith in the future of Canada. His nationalism was primarily central Canadian and English Canadian. He accepted the existence of a unique French Canadian community and especially a French Canadian claim to a due share of government patronage. But after the death of Sir George-Étienne Cartier in 1873, Macdonald did not share equal political power with a strong “Quebec lieutenant.” He also did not give senior cabinet positions to French Canadian politicians. His overriding national preoccupations were unity and prosperity. An 1860 speech summed up his lifelong political creed and goals: “One people, great in territory, great in resources, great in enterprise, great in credit, great in capital.”

Macdonald also had serious flaws. His political ruthlessness; the corruption that was exposed in the Pacific Scandal; and his role in the execution of Louis Riel have long been debated. His legislation concerning Chinese immigrants has been criticized as racist and discriminatory. His policies and attitudes toward Indigenous peoples have been seen as dehumanizing and paternalistic. As one of the architects of the residential school system, he has been held responsible by many Indigenous people for the intergenerational trauma they have endured.

Two hundred years after Macdonald’s birth, we have a more complex and more complete picture of Canada’s first prime minister. For good and ill, Macdonald, perhaps more than any other individual, helped make Canada what it is today.

See also Elections and Prime Ministers Timeline; Prime Ministers of Canada.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom