Early Life

Mackenzie Bowell was born in Rickinghall, Suffolk, England, the son of John Bowell and Elizabeth Marshall, in 1823. The family came to Canada in 1833 and settled in Upper Canada. As a boy, the young Bowell learned cabinetmaking from his father. Soon after his arrival in Belleville, he went to work for the local newspaper, The Intelligencer, as a printer’s apprentice for its editor and owner, George Benjamin, with whom he became close. In 1841, Bowell trained to be a teacher and received a diploma from Sydney Normal School in Hastings, a small community northwest of Belleville.

Militia Service

Mackenzie Bowell was a strong advocate and organizer for the militia in Hastings County. In 1857, he helped organize the First Volunteer Militia Rifle Company of Belleville. He served as an ensign with the company from 1858 to 1865 and later became its lieutenant colonel. Bowell saw active duty at Amherstburg, Upper Canada, amid the tensions of the American Civil War in 1864–65, and again in 1866 at Prescott, Upper Canada, during the Fenian raids. From 1867 to 1872, Bowell was lieutenant colonel of the 49th Hastings Battalion of Rifles.

Personal and Social Life

While he was an active supporter of the local militia, Mackenzie Bowell also devoted time and energy to his community by serving on the board of school trustees, grammar school board and board of agriculture and arts in Belleville. Bowell married Harriet Louise Moore in 1847 and, together, they had nine children.

Orange Order

Mackenzie Bowell was a devout Protestant and member of the Wesleyan Methodist Church. In 1842, he joined the Orange Order, a political and religious fraternal society that was founded in Ireland in 1795. In Canada, members defended Protestantism, promoted the country’s place in the British Empire and provided mutual aid and social activities. Additionally, the Orange Order was known to have had a strong influence in politics, particularly at the local level, and many members feared the influence of Catholics and French Canadians.

In 1860, Bowell was president of the Belleville Orange Lodge and helped organize a celebration for the Prince of Wales’ royal tour of Canada. However, the future King Edward VII shunned open displays of affection by the Orange Order throughout the colony, as he didn’t want to provoke tensions. Over time, Bowell rose through the ranks of the order and eventually served as Grand Master of British North America from 1870 to 1878. However, he didn’t always vote or enact legislation that reflected the Order’s wishes. In 1863, for instance, some Orangemen considered that Bowell, who was running for a seat in the colonial legislature, did not adequately oppose the enactment of legislation that allowed Catholic school boards. They therefore campaigned against him and contributed to his defeat at the polls. In the 1890s, Bowell defended Catholic prime minister John Sparrow David Thompson from faith-based attacks and sought to restore funds for Manitoba’s Catholic schools after the provincial government had stripped them (see Manitoba Schools Question). Both actions frustrated many Orangemen.

Newspaper Career

Bowell became a partner of The Intelligencer in 1848 and took on the role of editor. The following year, he and his brother-in-law became the newspaper’s publishers. By the early 1850s, Bowell was a leading figure in the Canadian newspaper industry. During this period, he became exclusive proprietor of The Intelligencer and transformed it from a weekly into a daily in 1867. In 1875, he incorporated the business as the Intelligencer Printing and Publishing Company. In addition, he was one of the founders of the Canadian Press Association in 1859 and became its president in 1865–66.

Political Life

Just as he had succeeded George Benjamin as newspaper editor, Mackenzie Bowell followed in his mentor’s footsteps as a politician as well. Bowell first ran as a Conservative candidate for the riding of Hastings North in the Province of Canada in 1863. Though he lost this first attempt, he remained interested in politics. He ran and won as a federal Conservative candidate in 1867 and held the riding of Hastings North continuously until 1892.

Bowell was a backbench Member of Parliament for his first few years. In 1874, though, he rose to greater prominence when he advocated for the expulsion of Louis Riel from the House of Commons. Four years earlier, during the Red River Rebellion, Riel had ordered the execution of Thomas Scott, an Orangeman from Bowell’s riding in Hastings. The fact that Riel was subsequently elected to the federal Parliament in the riding of Provencher angered many Ontarians but none more so than members of the Orange Order. Bowell, who was leader of the Order in Canada, introduced a motion to prevent Riel from taking his seat, and the famous Métis leader was later officially barred from the House of Commons. (See also Wilfrid Laurier: Speech in Defence of Louis Riel, 1874.)

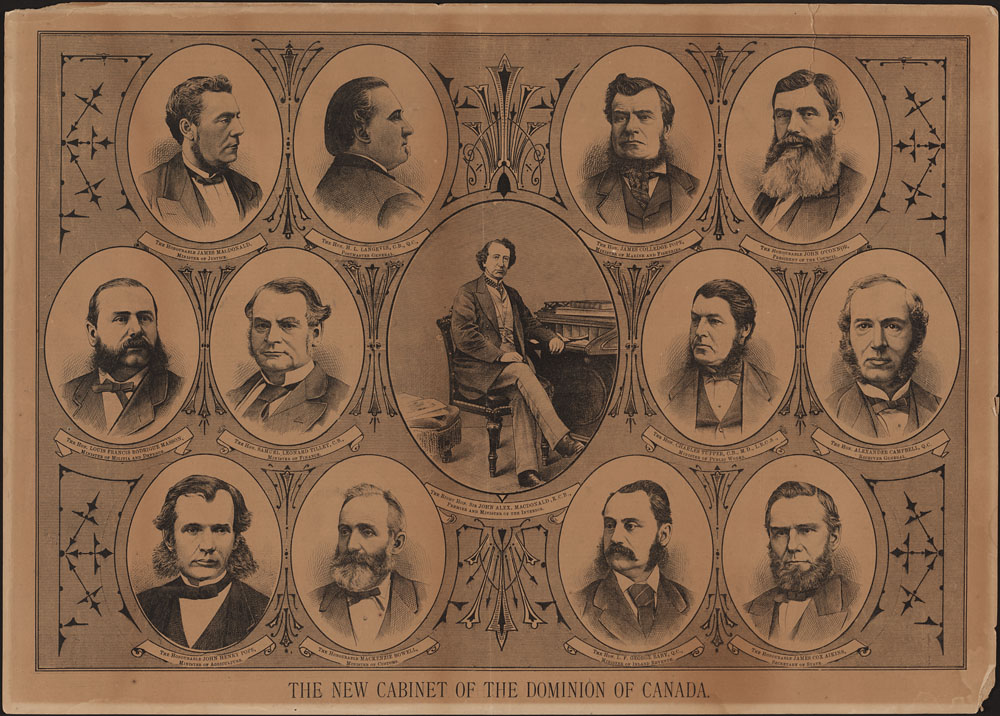

In 1878, Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald appointed Bowell to his Cabinet, making him Minister of Customs. Known to be a hard worker and an able administrator, Bowell held the position from 1878 to 1892. He was responsible for overseeing and regulating government revenue, a particularly important portfolio in the wake of the launch of the National Policy in 1879. The National Policy was the Conservatives’ principal economic initiative in late-19th-century Canada. The legislation ushered in tariffs on foreign goods as a means to protect Canadian businesses. Other cabinet portfolios under Bowell’s purview included railways and canals and, later, militia and defence.

When John S.D. Thompson took over as prime minister in December 1892, he named Bowell to the Senate. Given his government record, Bowell was also named Leader of the Government in the Senate and, though now outside the House of Commons, Minister of Trade and Commerce, a newly created but important portfolio. Bowell was deeply engaged in government affairs. From September 1893 to January 1894, he travelled to Australia with Sandford Fleming to discuss trade between Australasian colonies and Canada, as well as a proposed cable link between North America and Australia. The whole venture was tremendously successful, and soon thereafter Bowell proposed and organized another, larger conference to be held in Ottawa. In June 1894, the Colonial Conference saw British colonies, dominions and territories meet together for the first time. With Bowell as president, the conference examined opportunities for preferred rates and increased trade among intercolonial trading partners.

Prime Minister 1894–96

When Prime Minister John S.D. Thompson died in office in December 1894, there was no unanimous choice to succeed him. Because Mackenzie Bowell was the most senior member of the government and had served as acting prime minister on a couple of occasions when Thompson had been overseas, Governor General Lord Aberdeen chose him to head the new government. Like John Abbott before him, Bowell held the post of prime minister while serving in the Senate, not the House of Commons. During his tenure, Bowell was simultaneously president of the Privy Council.

The Manitoba Schools Question dominated Bowell’s term as prime minister. While revisions in the Manitoba Act of 1870 allowed for denominational (Catholic) schools, the Manitoba government stopped public funding for these schools in 1890. This led to a series of court challenges and cases and a Canadian population divided along linguistic, religious, political and jurisdictional lines.

Bowell supported legislation drafted in 1895 to restore Roman Catholic schools in the province, citing the need to adhere to the British North America Act. Nevertheless, it wasn’t implemented because of internal dissent within the Tory Cabinet and Bowell’s hesitancy to push through a policy. In short, he wasn’t sure what action to take or how to proceed to avoid significant backlash from party members and voters across the country. As a senator, Bowell could not debate the matter in the House of Commons, further deepening the frustration of party members.

In early January 1896, seven members of Bowell’s cabinet, including George Eulas Foster, resigned out of dissatisfaction with his governance. They called into question Bowell’s leadership and pressed the governor general, the Earl of Aberdeen, to name Charles Tupper as Bowell’s replacement. While he labelled the men a “nest of traitors” for their actions, Bowell succumbed to the pressure and resigned on 8 January 1896. However, the governor general refused to accept the resignation and intervened to help prop up support for the fledgling prime minister. The following week, six of the seven ministers returned to the Cabinet because they believed that Tupper, who was now back in Cabinet after an extended stay in London as the Canadian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom, would be the de facto party leader and that Bowell would resign. Bowell ultimately stepped down at the end of the parliamentary session on 27 April 1896.

Later Career

While relinquishing control of the Office of the Prime Minister, Bowell still kept his seat in the Senate. He remained Leader of the Government in the Senate until Liberal leader Wilfrid Laurier won the 1896 federal election. At that point, Bowell became Leader of the Opposition in the Senate, a position he held until 1906.

Although he resigned from politics that year, he retained his seat in the Senate and served on many senatorial committees to 1917. At the same time, Bowell returned to work at The Intelligencer in 1896 and continued to go to work at his newspaper office until 1913.

Death and Legacy

Bowell died of pneumonia in Belleville on 10 December 1917 at the age of 93. He is buried at Belleville Cemetery. While he was prime minister for a period of only 493 days, he was named a National Historic Person in 1945. The township of Bowell, Ontario (now part of the Municipal Township of Valley East), was named in his honour, as was the hamlet of Bowell, Alberta. Mount Sir Mackenzie Bowell is found in the Cariboo Mountains of British Columbia, in close proximity to other peaks named after Canadian prime ministers.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom