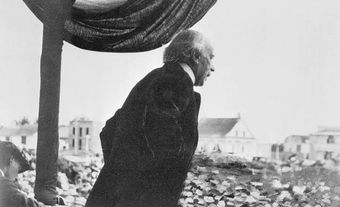

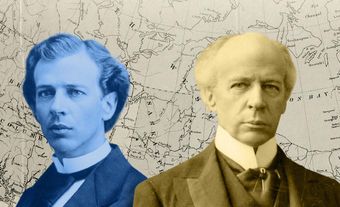

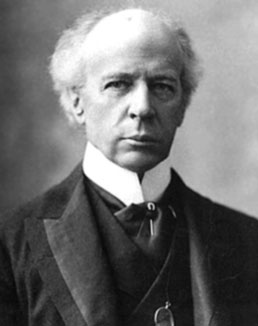

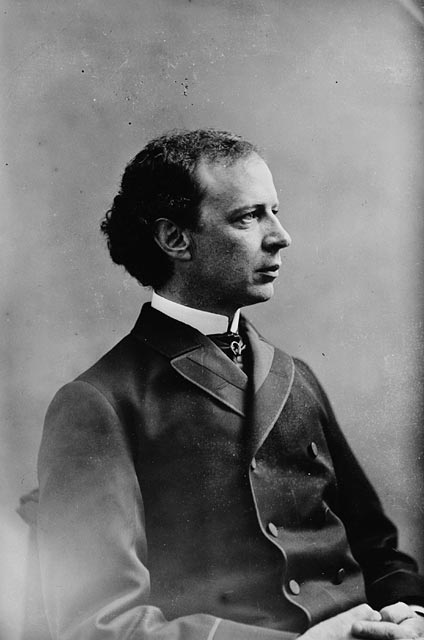

Sir Wilfrid Laurier, PC, prime minister of Canada 1896–1911, politician, lawyer, journalist (born 20 November 1841 in St-Lin, Canada East; died 17 February 1919 in Ottawa, ON). Sir Wilfrid Laurier was the dominant political figure of his era. He was leader of the Liberal Party from 1887 to 1919 and Prime Minister of Canada from 1896 to 1911. A skilful and pragmatic politician with a charismatic personality, he unceasingly sought compromise. Above all, he was a fervent promoter of national unity at a time of radical change and worsening cultural conflict. Laurier also promoted the development and expansion of the country. He encouraged immigration to Western Canada; supported the construction of transcontinental railways; and oversaw the addition of Alberta and Saskatchewan to Confederation.

Education and Early Career

Wilfrid Laurier studied law at McGill University. While there, he established close ties with radical members of the Parti Rouge. This included one of his professors, Toussaint-Antoine-Rodolphe Laflamme. Laurier also became vice-president (1864–66) of the Institut canadien; a literary society with Rouge links.

After graduating from McGill in 1864, Laurier briefly practiced law in Montreal. In 1866, he went to live in L’Avenir and then in Arthabaska, Quebec, where he ran the newspaper Le Défricheur. Like the Liberals of Canada East (present-day Quebec), Laurier opposed Confederation. He argued that the federal government would have too much power and that French Canadians would be overwhelmed.

In 1871, the Catholic Church in Quebec, led by Bishop Bourget, was ferociously attacking the Rouges and liberalism. In response, Laurier became the Liberal member for Drummond-Arthabaska in the Quebec legislature. Earlier, he had embraced radical liberalism; but now he became more moderate. He hoped this would be more acceptable to the Catholic clergy. (See also Wilfrid Laurier Speech: Parliamentary Debut, 1871.)

Like many other Liberals, Laurier also decided to accept Confederation as a fait accompli and to work within the new system. In 1874, he resigned his provincial seat and ran for election to the House of Commons. He held his seat in Ottawa uninterrupted for some 45 years.

Federal Politics

In October 1877, months after giving a vigorous speech in defence of liberalism, Laurier was appointed minister of inland revenue in Alexander Mackenzie’s Cabinet. Laurier was the most prominent Liberal from his province. He became the recognized leader of the Quebec wing of the party. However, his party’s defeats in the elections of 1878 and 1882 curbed his ambitions. He was re-elected in Québec-Est; but he took less interest in political debate.

In 1885, Laurier’s ardour was aroused by the hanging of Louis Riel. He vigorously defended the cause of the Métis leader and the need to unite the French and English in Canada. (See also Wilfrid Laurier Speech: In Defence of Louis Riel, 1874.) In 1887, Edward Blake was disappointed by the recent electoral defeat. He chose Laurier to succeed him as leader of the Liberal Party, despite the opposition of various eminent Liberals. They believed Laurier was too easygoing and too physically weak to be an effective leader. (Laurier suffered from chronic bronchitis for much of his life.) They also feared that Ontarians would associate him with Riel, and that Catholic clergy in Quebec still viewed him as a radical.

Leader of the Liberal Party

From 1887 on, Laurier devoted himself to building a truly national party and to gradually regaining power. His efforts were divided into two distinct phases. In the first and less successful, 1887–91, he pursued the policy of unrestricted reciprocity with the United States. Announced in 1888, the program was rejected in the 1891 general election. Laurier was perceived as a continentalist and as anti-British. He was rejected by the Canadian electorate; but for the first time since 1874, Liberals won a majority of the seats in Quebec.

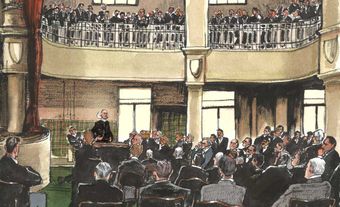

The second more fruitful phase took place between 1891 and 1896. This was the period when Laurier, more sure of himself, built a strong national Liberal Party. At the time, the Conservatives were mired in difficulties after the death of Sir John A. Macdonald. In 1893, Laurier organized an impressive political convention in Ottawa; there, the party approved a new program and the basis for a truly national structure.

In the 1896 election, the education rights of the Catholic minority in Manitoba became an important issue. In 1890, Manitoba Liberals had established a uniform school system in place of the separate school system enjoyed to that point. This prompted protest from the Catholic minority. (See Manitoba Schools Question.) Laurier avoided taking a definite stand; but French Canadians believed he would be more supportive of minority rights than the Conservatives. On 23 June 1896, Canadians chose Laurier over Conservative Charles Tupper to lead the country as prime minister. (See also Wilfrid Laurier Speech: “Sunny Ways,” 1895.)

Prime Minister of Canada

Contrary to the expectations of many French Canadians, Laurier did not champion the minority rights of Catholics in Manitoba. Instead, his focus as prime minister was on the country’s development and on healing the wounds to national unity. In 1896, he signed the Laurier-Greenway agreement. It decided the fate of educational rights for Manitoba’s Catholic minority. This group would never again have the separate schools it enjoyed prior to 1890; although it would be possible to obtain religious instruction during the last half-hour of the school day and instruction in a language other than English. (See also History of Education; Francophone-Anglophone Relations; Francophones of Manitoba.)

In the name of national harmony and the politics of the “lesser evil,” Laurier launched his policies of compromise. (See Sir Wilfried Laurier: The Politics of Compromise.) This approach kept him in power for many years. But it never completely redressed the wrongs committed against the Catholic minority.

Laurier adopted a similar approach to relations with Britain. Shortly after becoming prime minister, he began to reorganize the immigration system with Clifford Sifton. With William Fielding, he finalized the details of a tariff policy based on imperial preference. In 1897, Laurier went to London, England, to participate in his first colonial conference. He also received a knighthood.

Guided by his desire for Canada’s independence, Laurier resisted every effort Britain made toward federation of the empire in political, economic, or military terms. (See also Commonwealth.) Nonetheless, in 1899, he agreed to help defray the costs of transportation and matériel of Canadians wishing to fight for England in the South African War. This conciliatory stance was criticized by French Canadians who were fiercely opposed to any participation. However, Laurier and his Liberals easily won the 1900 election. They were well supported by Quebec; it gave the Liberals 57 of its 65 seats. Laurier’s personal popularity in Quebec likely played a key role in this result.

After this victory at the polls, Laurier led his country forcefully. Within cabinet, he directed policy and did not hesitate to push aside dissenters; these included the powerful Israël Tarte, who was forced to resign in 1902. That same year, Laurier also commanded attention outside the country. At the colonial conference in London, he again opposed all proposals to unify the Empire. In 1903, shortly after the failure of the Alaska Boundary discussions with the US, Laurier revealed the most important policy of his second term; the construction of a second transcontinental railway.

The Transcontinental Railway

The Grand Trunk Pacific Railway would build the section from Winnipeg westward. The federal government would undertake the construction of a line (called the National Transcontinental) from Moncton and Quebec City to Winnipeg. Laurier was so optimistic about the nation’s progress that he allowed the Canadian Northern Railway to build a third transcontinental line. By agreeing to multiple railways, much of it at public expense, Laurier mortgaged the future with a heavy financial burden. At the peak of his prestige, he allowed nothing to check his ambitions. Canadians re-elected him with a comfortable majority on 3 November 1904. (See also Wilfrid Laurier Speech: Canada’s Century, 1904.)

The Creation of Alberta and Saskatchewan

In 1905, Laurier succeeded in adding two new provinces to the Dominion of Canada: Alberta and Saskatchewan. (See also Wilfrid Laurier Speech: Let Them Become Canadians, 1905.) However, the addition of these provinces also meant that a decision had to be made regarding the educational rights of the Catholic minority. Once again, Laurier yielded to pressure from anglophones and Protestants. But in deferring to the status quo of one uniform school system, he deprived a minority group of separate schools. As a result, the last chance to establish genuine cultural duality throughout Canada was lost.

Offended by this retreat, French Canadian nationalists bitterly criticized Laurier. His prestige in Quebec began to fade. This led to the progressive decline of the Laurier government. In the years that followed, Laurier mainly sought to counter accusations of corruption and patronage within his administration and to rebuild his Cabinet.

In the 1908 general election, Canadians once again entrusted him with their destiny. His party’s majority was somewhat reduced, but it was still quite strong in Quebec. After 1908, Laurier focused his attention primarily on two bills. They ultimately led to his defeat.

Controversial Policies and Defeat at the Polls

In 1910, the Naval Service Act established a Canadian navy of five cruisers and six destroyers. They would be ready to fight with Great Britain anywhere in the world. However, this was insufficient in the eyes of English Canadian imperialists. French Canadian nationalists led by Henri Bourassa, meanwhile, considered it excessive. This moderate measure would cost Laurier precious support, especially in Quebec.

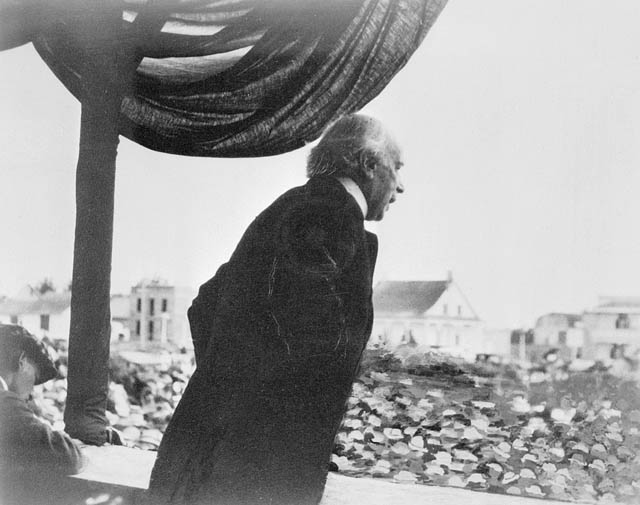

The second bill concerned reciprocity with the US; the old Liberal dream of 1891. Brought to the Commons early in 1911, it permitted the free trade of most natural products; but only a small number of manufactured products. Despite the attractions of the plan, it raised the ire of Canadian industrialists. As such, it provided a weakness for the Conservative Party under Robert Borden to exploit. They accused the Liberals of disloyalty toward England and of leading the country toward political annexation. To settle the issue, Laurier called a general election. On 21 September 1911, he suffered a bitter defeat.

Leader of the Opposition

Laurier proved to be an energetic and vigilant leader of the Opposition. He failed to adapt his liberalism as progressive Liberals would have wished; but he kept his troops united until at least 1916. He also relentlessly attacked the Borden government’s failure to address problems such as the rising cost of living. (See Standard of Living.)

Laurier achieved some success in rebuilding the Liberal Party. Prior to 1914, he fought mainly against the emergency contribution of $35 million offered to Great Britain to help strengthen its navy. He also opposed the financial assistance given to the Canadian Northern Railway. In 1916, he defended the rights of Franco-Ontarians to bilingual instruction in schools. This increased his popularity among French Canadians. (See also Wilfrid Laurier Speech: Faith Is Better than Doubt and Love Is Better than Hate, 1916.)

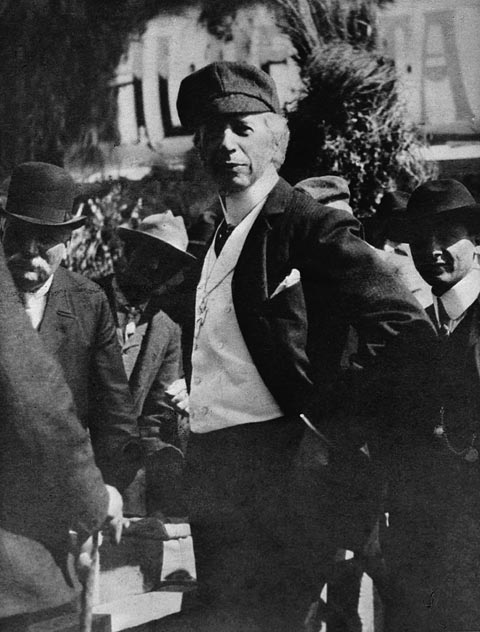

Out of personal conviction, Laurier vigorously supported Canadian participation in the First World War. He ardently promoted voluntary enrolment and proposed a political truce. In 1915–16, at age 75, he held several recruiting meetings. In 1917, the country was plunged into national crisis following the imposition of military conscription. Laurier again turned to compromise. To save Canada’s threatened unity, he refused to support this measure, which was so repulsive to Quebec; instead, he proposed a referendum and continued voluntary enlistment. This time, however, his proposal was not supported by the majority of English Canadians. The formula collapsed in general bitterness.

Laurier was opposed by English Canadians and idolized by French Canadians; he became a symbol of division within the country. His own party disintegrated when several eminent English Canadian Liberals crossed the floor to join the Union Govenment. Laurier refused to participate. In the general election of December 1917, he was overwhelmingly defeated by Borden’s Unionist Party. The vote was divided along distinctly cultural lines.

After the Armistice was declared on 11 November 1918 and the First World War came to an end, Laurier began his attempts to restructure his party and to rebuild Canadian unity; but he died on 17 February 1919.

Legacy

Under Laurier’s leadership, Canada successfully continued to industrialize and urbanize. It was strengthened by the addition of two provinces and two million inhabitants. A clever and eloquent politician, Laurier was a true legend in his time. He has been judged in a variety of ways. For some, he was the spiritual successor to Sir John A. Macdonald, who pursued and consolidated Confederation. For others, Laurier, in the name of national unity and necessary compromise, too often sacrificed the interests of French-Canadian Catholics to those of the majority. Conversely, some think he too often governed the country with only Quebec’s interests in mind. Support for each of these opinions can be found in Laurier’s actions in Ottawa; but the last view is most open to argument.

See also Canada’s Century: Sir Wilfrid Laurier’s Bold Prediction; Wilfrid Laurier House National Historic Site of Canada; Collection: Sir Wilfrid Laurier; Timeline: Sir Wilfrid Laurier; Education Guide: Sir Wilfrid Laurier; Timeline: Elections and Prime Ministers.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom