An Act for the Abolition of Slavery throughout the British Colonies; for promoting the Industry of the manumitted slaves; and for compensating the Persons hitherto entitled to the Service of such Slaves (also known as the Slavery Abolition Act) received Royal Assent on 28 August 1833 and took effect 1 August 1834. The Act abolished enslavement in most British colonies, freeing over 800,000 enslaved Africans in the Caribbean and South Africa as well as a small number in Canada.

Background

Several factors led to the Act’s passage. Britain’s economy was in flux at the time, and as a new system of international commerce emerged, its slaveholding Caribbean colonies — which were largely focused on sugar production — could no longer compete with larger plantation economies such as Cuba and Brazil. Merchants began to demand an end to the monopolies on the British market held by the Caribbean colonies and pushed instead for free trade. The persistent struggles of enslaved Africans and a growing fear of slave uprisings among plantation owners was another major factor.

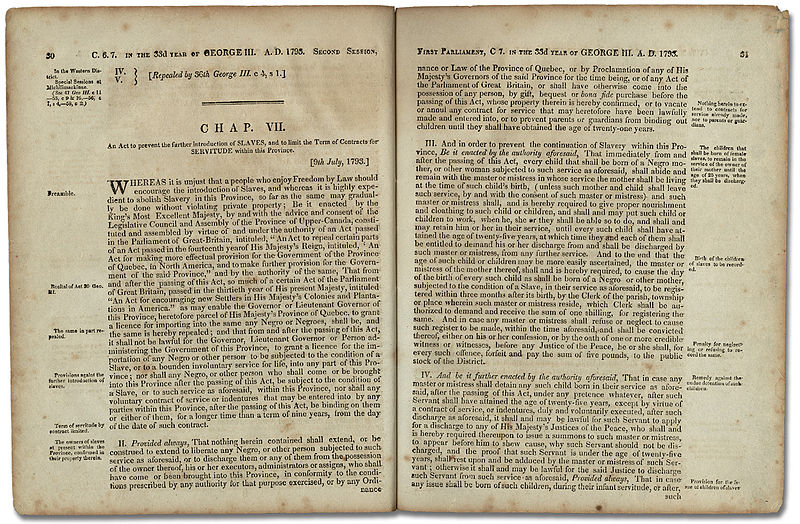

British abolitionists had actively opposed the transatlantic trade in African people since the 1770s. (Several abolitionist petitions were organized in 1833 alone, which collectively garnered the support of 1.3 million signatories.) Such anti-slavery views spread to Upper Canada, influencing the passage of the 1793 Act to Limit Slavery, the first legislation that aimed to dismantle slavery in the British colonies. ( See Chloe Cooley and the Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada.)

Legal Challenges to Slavery in British North America

In the eastern colonies of Lower Canada (what is now Québec), Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, previous abolitionist attempts had been unsuccessful. In 1793, for instance, Pierre-Louis Panet introduced a bill to the National Assembly to abolish enslavement in Lower Canada, but the bill languished over several sessions and never came to a vote (see Panet Family).

Instead, individual legal challenges first raised in the late 1700s undermined the institution of enslavement in these areas. One important case came in February 1798, when an enslaved woman named Charlotte was arrested in Montréal and refused to return to her mistress. She was brought before James Monk, a justice of the King’s Bench with abolitionist sympathies, who released Charlotte on a technicality. According to British law, enslaved persons could only be detained in houses of corrections, and not common jails, and as no houses of correction existed in Montréal, Charlotte could not be detained. She and another enslaved woman named Judith were freed that winter. Monk stated in his ruling that he would apply this interpretation of the law to subsequent cases. Another significant 1798 case came before the courts in Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia, when a local military officer Frederick William Hecht sought to establish his title to an enslaved woman named Rachel Bross. After a lengthy trial, the jury rejected Hecht’s claim, ruling instead that Bross was a free servant.

Rulings in such cases did not always favour emancipation, however. Only two years after the trials of Charlotte and Bross, an enslaved woman named Nancy petitioned for her freedom in the New Brunswick courts. Fourteen years earlier, Nancy had run away with her son and three others, but they were caught and returned to her previous owner, a farmer and Loyalist settler named Caleb Jones. The challenge filed by her attorneys was that slavery was a socially accepted custom, but was not officially recognized in New Brunswick. The judges’ decision was split, and Nancy remained enslaved.

Impact of the Act

Following from the 1793 Act to Limit Slavery, Upper Canada was already moving toward abolition. The Slavery Abolition Act, 1833, did not reference British North America. Rather, its aim was to dismantle large-scale plantation slavery that existed in Britain’s tropical colonies, where the enslaved population was usually larger than that of the white colonists. Enslaved Africans in British North America were far smaller in number and lived, according to Frank Mackey, “scattered and isolated from one another.”

As an imperial statute, the Slavery Abolition Act liberated less than 50 enslaved Africans in British North America. For most enslaved people in British North America, however, the Act resulted only in partial liberation, as it only emancipated children under the age of six, while others were to be retained for four to six years as apprentices. Twenty million English pounds (£20,000,000) were made available by the British government to pay for damages suffered by owners of registered slaves, but none was sent to slaveholders in British North America. Those formerly enslaved did not receive any compensation either.

This legislation also made Canada free land for enslaved black Americans. The image of Canada as a safe haven for enslaved African Americans was born, and thousands of fugitives and free black Americans would arrive on Canadian soil between 1834 and the early 1860s. ( See also Underground Railroad.)

Legacy

The passage of the Slavery Abolition Act gave rise to a significant cultural event called Emancipation Day, which continued to grow in popularity throughout the 19th century. Once a year, beginning in 1834, the liberation of enslaved Africans and the idea of freedom are recognized in the West Indies and parts of the United States and Canada. Members of the African Canadian community along with white and Indigenous supporters gather at various locations across the country to commemorate the abolition of slavery throughout the British colonies on 1 August. Celebrants parade through main streets, and attend church services and speeches. Picnics, dances and other festive cultural activities are held in celebration. Emancipation Day commemorations also serve as a platform from which to challenge the racial discrimination that has impeded Black Canadians’ ability to exercise their full rights and freedoms.

The end of enslavement in most of the British colonies was an important turning point in history, one that transformed the social condition of African people in the Caribbean, South America and North America. Racial inequality and anti-Black racism is a legacy of enslavement and has been resisted by the Black civil rights agenda internationally. Black persons in Canada were denied certain rights and privileges and limited to menial jobs. Many Black parents were forced to send their children to segregated schools. Black men and women were refused service by many white-owned businesses and denied the right to purchase property in certain areas.

One lingering issue from the period of African enslavement is the matter of reparations. In 2013, the Caribbean Community CARICOM, an organization of 15 Caribbean countries, formed a committee to pursue reparations from Britain and seven other European countries that profited from enslavement. The committee is seeking formal apologies and some form of compensation for the benefit of Africans in the diaspora.

The question of reparations for descendants of Africans enslaved and systemically discriminated against in Canada has also been raised. In 2004, the United Nations supported the demand for compensation for the destruction of Africville by the City of Halifax. Like their Caribbean counterparts, African Canadians seek formal apologies and a discussion with the different levels of government on possible forms of compensation.

See also Black History in Canada.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom