Taxes are mandatory payments by individuals and corporations to government. They are levied to finance government services, redistribute income, and influence the behaviour of consumers and investors. The Constitution Act, 1867 gave Parliament unlimited taxing powers and restricted those of the provinces to mainly direct taxation (taxes on income and property, rather than on activities such as trade). Personal income tax and corporate taxes were introduced in 1917 to help finance the First World War (see Income Tax in Canada). The Canadian tax structure changed profoundly during the Second World War. By 1946, direct taxes accounted for more than 56 per cent of federal revenue. The federal government introduced a series of tax reforms between 1987 and 1991; this included the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST). In 2009, the federal, provincial and municipal governments collected $585.8 billion in total tax revenues

Taxing Powers

The first recorded tax in Canada appears to date back to 1650. An export tax of 50 per cent on all beaver pelts, and 10 per cent on moose hides, was levied on the residents of New France.

Today, of the various methods available for financing government activities, only taxation payments are mandatory. Taxes are imposed on individuals, business firms and property. They are used to finance public services or enable governments to redistribute resources. Taxation allows governments to increase expenditures without causing price inflation, because private spending is reduced by an equivalent amount.

The Constitution Act, 1867 gave Parliament unlimited taxing powers. It also restricted those of the provinces to mainly direct taxation (taxes on income and property, rather than on activities such as trade). The federal government was responsible for national defence and economic development; the provinces for education, health, social welfare and local matters which then involved only modest expenditures. (See Distribution of Powers.) The provinces needed access to direct taxation mainly to enable their municipalities to levy property taxes.

Early 20th Century

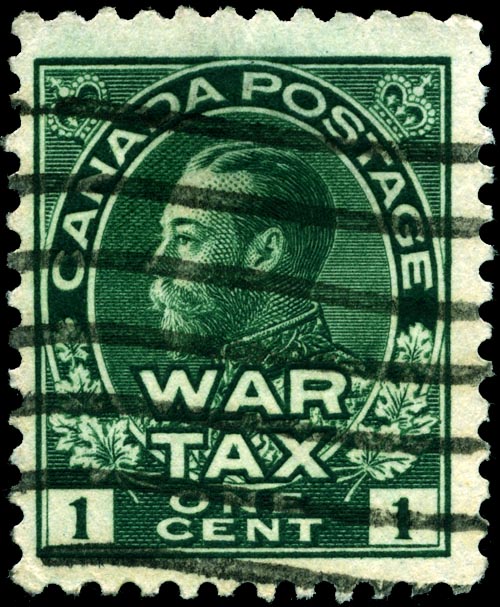

For more than 50 years after Confederation, customs and excise duties provided the bulk of federal revenues; by 1913, they provided more than 90 per cent of the total. However, to help finance the First World War, Parliament introduced corporate taxes and personal income taxes. (See also Sir Robert Borden.) The 1916 Business Profits War Tax Act applied a federal tax on a percentage of business profits. The Income War Tax Act, which received royal assent on 20 September 1917, introduced a tax on annual personal income (see Income Tax in Canada). In 1920, a manufacturers’ sales tax and other sales taxes were also introduced.

Provincial revenue at this time came primarily from licences and permits; as well as the sales of commodities and services. In addition, the provinces received substantial federal subsidies. (See also Transfer Payments.) They hesitated to impose direct taxes; but by the late 1800s, they were taxing business profits and successions. Taxes on real and personal property were the bulwark of local government finance. By 1930, total municipal revenues surpassed those of the federal government.

The Great Depression bankrupted some municipalities and severely damaged provincial credit. Customs and excise duties declined by 65 per cent from 1929 to 1934. Parliament resorted more to personal and corporate taxation; it also raised sales taxes dramatically. Before the Depression was over, all provinces were taxing corporate income. All but two provinces levied personal income taxes, and two had retail sales taxes.

Second World War

The Canadian tax structure changed profoundly during the Second World War. To distribute the enormous financial burden of the war equitably, to raise funds efficiently and to minimize the impact of inflation, the major tax sources were gathered under a central fiscal authority. In 1941, the provinces agreed to surrender the personal and corporate income tax fields to the federal government for the duration of the war and for one year after. In exchange, they received fixed annual payments. (See Transfer Payments.) In 1941, the federal government introduced succession duties (on the transfer of assets after death). An excess profits tax was imposed. Other federal taxes increased drastically.

By 1946, direct taxes accounted for more than 56 per cent of federal revenue. The provinces received grants, and the yields from gasoline and sales taxes increased substantially. The financial position of the municipalities improved with higher property tax yields. In 1947, contrary to the 1942 plan, federal control was extended to include succession duties as well. However, Ontario and Quebec opted out; they chose to operate their own corporate income tax procedures. There was public pressure for federal action in many areas. The White Paper on Employment and Income advocated federal responsibility for these areas.

As a result, direct taxes became a permanent feature of federal finance. But the provinces also have a constitutional right to these taxes. There is a growing demand for services under provincial jurisdiction; such as health, education and social welfare. The difficulties of reconciling the legitimate claims of both levels of government for income taxation powers have since dominated many federal-provincial negotiations. (See Intergovernmental Finance; Federal-Provincial Relations.)

Late 20th Century

From 1947 to 1962, the provinces, with mounting reluctance, accepted federal grants as a substitute for levying their own direct taxes. In 1962, however, Ottawa reduced its own personal and corporate income tax rates to make tax room available to the provinces. Because taxpayers would pay the same total amount, provincial tax rates would not be risky politically. Further federal concessions between 1962 and 1977 raised the provincial share of income tax revenues significantly.

Provincial income tax calculations were traditionally integrated into federal tax returns. All provinces except Quebec used the federal definition of taxable income. (Quebec has operated its own income tax since 1954.) Provincial tax rates, which now differ considerably among the provinces, were simply applied to basic federal tax. In recent years, that trend has been weakening. For example, in Ontario, personal income tax payable is now calculated separately from federal income tax payable.

Principles of Taxation

Fairness

The criteria by which a tax system is judged include equity; efficiency; economic growth; stabilization; and ease of administration and compliance. According to one view, taxes, to be fair, should be paid in accordance with the benefits received. But the difficulty of assigning the benefits of certain government expenditures — such as defence — restricts the application of this principle. Provincial gasoline taxes are one instance of the benefit principle, with fuel taxes providing revenue for roads and highways.

According to another view, individuals should be taxed based on their ability to pay (typically indicated by income). The personal income tax is in part a reflection of this principle. Horizontal equity (individuals with equal incomes are treated equally) is not easily achieved; this is because income alone is an imperfect measure of an individual’s ability to pay.

Vertical equity (higher incomes are taxed at higher rates than lower incomes — a principle not at odds with horizontal equity) has been opposed by business and those with higher incomes. They claim that progressive tax rates discourage initiative and investment. At the same time, under a progressive tax system, deductions benefit those with high taxable incomes. In recent years, this realization has led governments to convert many deductions to tax credits. However, this significantly complicates the tax preparation process.

Limiting Growth

Taxes can affect the rate of economic growth as well. Income taxes limit capital accumulation. Corporate and capital taxes reduce capital investment. Payroll taxes reduce job creation. Businesses in Canada have strongly opposed the full inclusion of corporate gains as taxable income. As a result, only 50 per cent of capital gains were taxable when the capital gains tax was introduced in 1972. The inclusion rate for capital gains was raised to 75 per cent by 1990. It was cut back to 50 per cent in 2000.

Shifting and Incidence

Taxes levied on some persons but paid ultimately by others are “shifted” forward to consumers wholly or partly by higher prices; or, they are “shifted” backward on workers if wages are lowered to compensate for the tax. Some part of corporate income taxes, federal sales and excise taxes, payroll taxes and local property taxes is shifted. This alters and obscures the final distribution of the tax burden.

Revenue Elasticity

The more elasticity (the percentage change in tax revenue resulting from a change in national income) a tax has, the greater its contribution to economic stabilization policy. Income taxes with fixed monetary exemptions and rate brackets have an automatic stabilization effect. This is because tax collections will grow faster than income in times of economic growth; conversely, they will fall more sharply than income in a recession.

In Canada, the revenue elasticity of personal income tax is weakened by indexing. Since 1974, both personal exemptions and tax brackets have been adjusted according to changes in the Consumer Price Index. But sales taxes have less revenue elasticity because consumption changes less rapidly in response to changes in income, and these taxes are not progressive in relation to consumption. Property tax yields do not grow automatically with rising national income; but they do exhibit some revenue elasticity.

Current Tax System

Taxes levied by all levels of government in Canada account for most of their revenues. The remainder comes from intergovernmental transfers (particularly from the federal government to the provinces), as well as investment income and other sources. In 2009, the federal, provincial and municipal governments collected $585.8 billion in total tax revenues. This amount included income tax; property tax; sales and other consumption taxes; payroll taxes; social security plans and health insurance premiums; and corporate taxes.

Federal Tax Revenues

In 2009, federal government revenues totalled $237.4 billion. Roughly 90 per cent was raised through taxes; $153 billion came from income taxes and $42.5 billion from consumption taxes and a range of other levies.

Personal income tax applies to all income sources of residents of Canada; except for such amounts as gifts, inheritances, lottery winnings, and veterans disability pensions. In addition, certain other amounts, such as workers’ compensation payments and some income-tested or needs-tested social assistance payments, must be reported as income; but they are not taxed.

Provincial Tax Revenues

In 2009, combined provincial government revenues totaled $308 billion. This included $95.7 billion in income taxes; $64.5 billion in consumption taxes; and more than $28 billion in property and other taxes. Another $60.5 billion in provincial revenues came in the form of transfer payments, mostly from the federal government.

Municipal Tax Revenues

In 2009, combined local government revenues across Canada totaled $121.8 billion. This included $46.2 billion in property taxes and approximately $1 billion in other taxes. The largest source of local government revenue was transfers from other levels of government, mostly the provinces; this amount totalled $51.7 billion in 2009. (See also Municipal Finance.)

Municipal tax bases vary considerably throughout Canada. The principal component of the municipal tax base in all provinces and territories is real property; this includes land, buildings and structures. Machinery and equipment affixed to property are included in the property tax base in Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, Alberta (where a municipal business tax does not exist), the Northwest Territories and the Yukon.

In Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick and Saskatchewan, machinery, equipment and other fixtures are liable to property taxation only when they provide services to the buildings. British Columbia removed all machinery and equipment from its property tax base in 1987.

Probably the strongest criticism against the residential property tax is that it is regressive. Since the 1960s, provincial and local government commissions have recommended changes in the existing property tax system to make it more equitable and efficient. In response, Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, Alberta and British Columbia introduced a property tax credit. Other general reforms have included broadening the tax base by reducing or eliminating some exemptions; as well as implementing equalized assessment.

Federal Tax Reform, 1987–91

In June 1987, the federal government introduced Stage One of Tax Reform. It included proposals for reform of the personal and corporate income tax structure. Bill C-139 took effect on 1 January 1988, although some changes were to be phased in over a longer period.

Income tax

In line with tax reform in other countries, Bill C-139 broadened the tax base for both personal and corporate income. It also reduced the rates applicable to taxable income. The bill replaced exemptions with credits and eliminated some deductions for personal income tax. It also replaced the 1987 rate schedule, with its 10 brackets and rates ranging from 6 to 34 per cent, with a schedule containing only three brackets with rates of 17 per cent, 26 per cent, and 29 per cent. (As of 2015, there were four federal brackets with rates of 15 per cent, 22 per cent, 26 per cent and 29 per cent. The 2015 rates in the provinces and territories ranged from 4 per cent to 25.75 per cent, according to income level.)

Capital Gains, Dividends and Business Taxes

Bill C-139 also capped the lifetime capital gains exemption at $100,000. (As of 2013, the lifetime exemption was $750,000. This was available only to owners of businesses, farms or fishing properties). The Bill also reduced capital cost allowances; introduced limitations on deductible business expenses; and lowered the dividend tax credit.

Goods and Services Tax (GST)

In 1991, the federal government introduced Stage Two of Tax Reform. As part of this reform effort, Ottawa initially proposed a national value-added tax; it would merge the new federal sales tax and the provincial retail sales taxes. The federal government was unable to get approval from the provincial governments for this proposal; instead, it continued with Stage Two of Tax Reform and replaced the manufacturers’ sales tax with the Goods and Services Tax (GST).

The manufacturers’ sales tax was difficult to administer; it was also widely criticized for placing an unequal tax burden on different consumer purchases. With a broadly based, multi-stage sales tax such as the GST, tax is collected from all businesses in stages, as goods (or services) move from primary producers and processors to wholesalers, retailers and finally to consumers.

The GST has some advantages over the old manufacturers’ sales tax. It eliminates tax on business inputs and treats all businesses in a consistent manner. It ensures uniform and effective tax rates on the final sale price of products. Finally, it treats imports in the same manner as domestically produced goods. It also completely removes hidden federal taxes from Canadian exports.

When the GST came into effect on 1 January 1991, provincial governments (except Alberta, which has no Provincial Sales Tax) had to decide how to manage the relationship between the federal sales tax (GST) and their own provincial sales taxes (PST). Quebec and the Atlantic Provinces chose to impose their retail sales tax on the selling price, including the goods and services tax. This raised their retail sales tax base. The remaining provinces, however, opted to impose their sales taxes on the price before the goods and services tax was added. This reduced their retail sales tax base.

Following the introduction of the GST, the federal government continued discussions on its original proposal with several provinces. The aim was to harmonize the GST with the provincial sales taxes. Initially, only Quebec agreed to merge its provincial sales tax with the federal sales tax. As of 2015, the Atlantic Provinces and Ontario had also merged their sales taxes; this created the single Harmonized Sales Tax (HST) in those provinces rather than two sales taxes (PST and GST). Quebec, meanwhile, administers its own harmonized system with the Quebec Sales Tax (QST) and the GST. Alberta is the only province without a sales tax.

Federal-Provincial Fiscal Arrangements

Three major money transfer programs have formed the bedrock of federal-provincial fiscal arrangements: Established Programs Financing (introduced in 1977); equalization payments; and the Canada Assistance Plan (introduced in 1966). (See also Intergovernmental Finance; Federal-Provincial Relations.) Formulas have changed over the years. But the broad goal of these programs and their successors has been to foster more equality among Canada’s regions. This is achieved by transferring funds, via the tax system, from the richer provinces to those that are less well off.

As of 2015 there were four major transfer programs. These included the Canada Health Transfer (CHT); the Canada Social Transfer (CST); equalization payments; and Territorial Formula Financing (TFF). The CHT and CST are federal transfers to the provinces. They support specific policy areas such as health care; post-secondary education; social assistance and social services; early childhood development; and child care. In 2015–16, total federal transfers to provinces were projected to reach $68 billion.

Trends in Government Financing

One of the biggest challenges facing all levels of government in the 21st century has been Canadians’ increasing reluctance to pay the higher taxes needed to fund the services they want. This trend began to manifest as far back as the early 1990s in the mounting dissatisfaction with Prime Minister Brian Mulroney’s government, following implementation of the GST. In the 2008 federal election, Opposition leader Stéphane Dion tried but failed to convince the public of the need for a carbon tax; despite Canadians’ support for action on climate change.

Politicians of all stripes took their cues from these and similar developments. In recent years, governments have thus shifted revenue collection strategies from visible tax increases to less opaque techniques; these include increased borrowing, money printing, and the use of accounting standards that do not require full recording of public-sector liabilities.

Borrowing to finance public spending has proven to be particularly popular among all governments around the Western world. (See also Budgetary Process.) This technique enables politicians to get the credit for the benefits the spending generates. Debt burdens, meanwhile, are transferred to the country’s youth; they are either not allowed to vote, or are not as well organized in strong lobby groups (as are seniors, the wealthy or various business interests).

Incurring unfunded liabilities (e.g., making promises related to public sector pensions and health care benefits, without setting aside the funds to pay for them) is another favored way of financing spending. It does not involve immediate taxation.

In the era after the 2008–09 recession, “money printing,” in the form of central bank purchases of government bonds, became increasingly popular. This is due to the challenges many governments face in raising money thanks to the near-zero levels of real interest rates they are paying on many of their bonds. The United States, the European Union and the Bank of Japan have all made major initiatives in this area.

See also: Income Distribution; Municipal Finance; Customs and Excise; Department of Finance; Fiscal Policy.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom