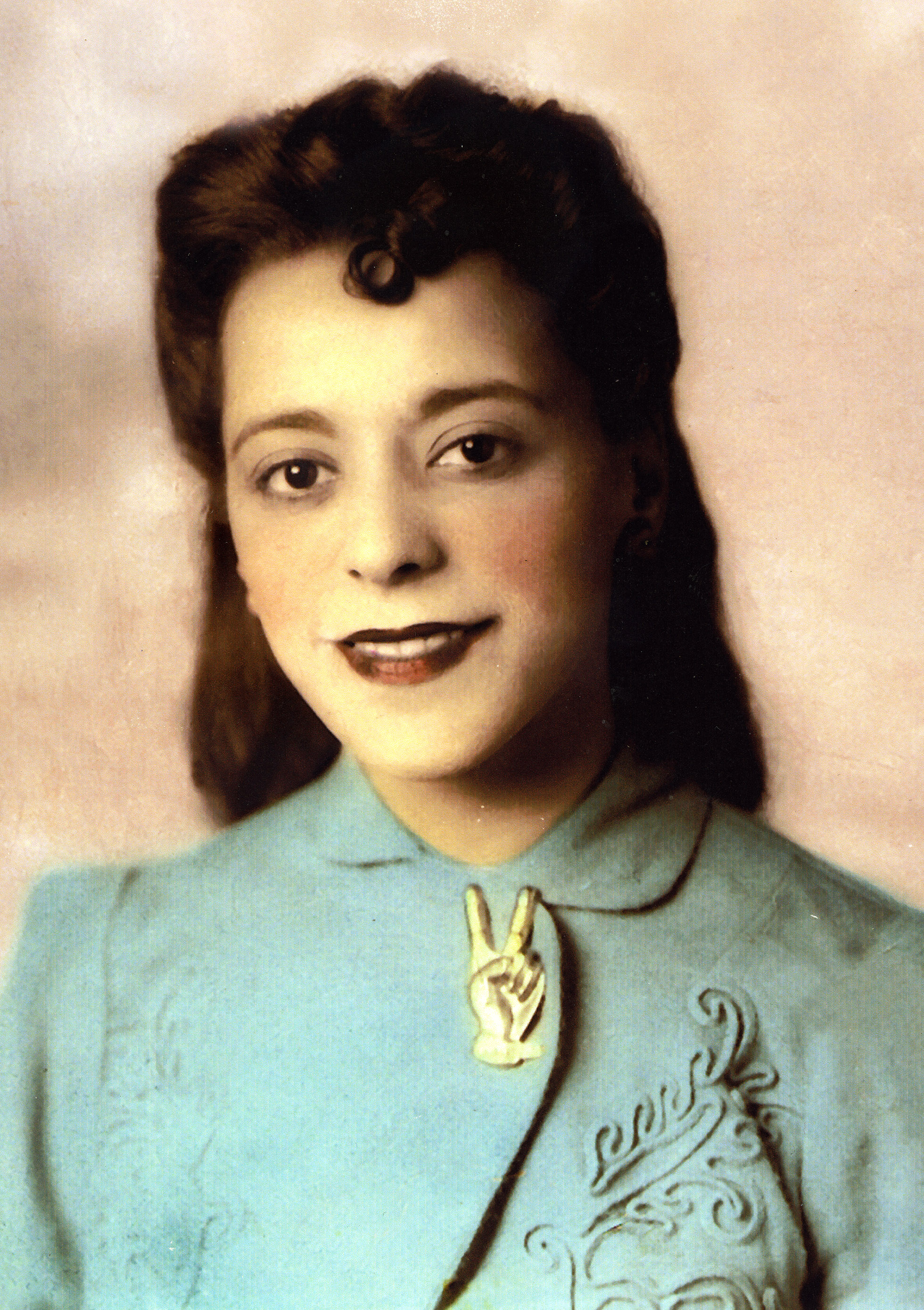

Early Life and Family

Viola Desmond was brought up in a large family with 10 siblings. Her parents were highly regarded within the Black community in Halifax. Her father, James Albert Davis, was raised in a middle-class Black family, and had worked for several years as a stevedore before establishing himself as a barber. Her mother, Gwendolin Irene Davis (née Johnson), was the daughter of a White minister and his wife, who had moved to Halifax from New Haven, Connecticut. Although racial mixing was not uncommon in early 20th-century Halifax, intermarriage was rare. Nonetheless, her parents were accepted into the Black community and became active and prominent members of various community organizations.

Motivated by her parents’ example of hard work and community involvement, Desmond aspired to success as an independent businesswoman. After a short period teaching in two racially-segregated schools for Black students, she began a program of study at the Field Beauty Culture School in Montreal, one of the few such institutions in Canada at the time that accepted Black applicants. She continued her training in Atlantic City and in New York. Desmond opened Vi’s Studio of Beauty Culture in Halifax, catering to the Black community.

Entrepreneur and Community Leader

In the early part of the 20th century, with the advent of new hair styles that demanded special product and maintenance, and an emphasis on fashion trends and personal grooming, beauty parlours offered opportunities for female entrepreneurs. Black women in particular were able to discover opportunity not otherwise available. Beauty parlours became a centre of social contact within the Black community, allowing the shop owner to achieve a position of status and authority.

Viola Desmond quickly found success. She opened a beauty school, the Desmond School of Beauty Culture, to train women and expanded her business across the province. (Desmond created a line of beauty products, which were sold at venues owned by graduates of her beauty school.) Aware of her obligation to her community, Desmond created the school in order to provide training that would support the growth of employment for young Black women. Enrolment in Desmond’s school grew rapidly, including students from New Brunswick and Quebec. As many as 15 students graduated from the program each year.

Although racism was not officially entrenched in Canadian society, Black persons in Canada, and certainly in Nova Scotia, were aware that an unwritten code constrained their lives. Sometimes the limits were difficult to foresee. In a way, the “unofficial” character of Canadian racism made it more difficult to navigate. (See also Prejudice and Discrimination.)

Did you know?

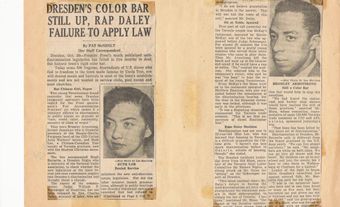

In 1943, Hugh Burnett went to a restaurant in Dresden, Ontario, wearing his army uniform. To his dismay, the owner would not serve him. Burnett promptly wrote to the federal Minister of Justice, Louis St-Laurent, informing him that, “even in uniform a Black man could not be served in any Dresden restaurant.” The Deputy Minister’s reply simply stated that there was no law against racial discrimination in Canada.

Roseland Theatre

On the evening of 8 November 1946, Viola Desmond made an unplanned stop in the small community of New Glasgow after her car broke down on her way to a business meeting in Sydney, Nova Scotia. Told that the repair would take several hours, she arranged for a hotel room and then decided to see a movie to pass the time.

At the Roseland Theatre, Desmond requested a ticket for a seat on the main floor. The ticket seller handed Desmond a ticket to the balcony instead, the seating generally reserved for non-White customers. Walking into the main floor seating area, she was challenged by the ticket-taker, who told her that her ticket was for an upstairs seat, where she would have to move. Thinking that a mistake had been made, Desmond returned to the cashier and asked her to exchange the ticket for one downstairs. The cashier refused, saying, “I’m sorry but I’m not permitted to sell downstairs tickets to you people.” Realizing that the cashier was referring to the colour of her skin, Desmond decided to take a seat on the main floor anyway.

Desmond was then confronted by the manager, Henry MacNeil, who argued that the theatre had the right to “refuse admission to any objectionable person.” Desmond pointed out that she had not been refused admission and had in fact been sold the ticket, which she still held in her hand. She added that she had attempted to exchange it for a main floor ticket and was willing to pay the difference in cost but had been refused. When she declined to leave her seat, a police officer was called. Desmond was dragged out of the theatre, injuring her hip and knee in the process, and taken to jail. There she was met by the Elmo Langille, chief of police, and MacNeil — the pair left together, returning an hour later with a warrant for Desmond’s arrest. She was then held in a cell overnight. Shocked and frightened, she maintained her composure and, as she later explained, sat bolt upright all night long.

Did you know?

The Fred Christie Case (1939) is a decision of the Supreme Court of Canada that allowed private businesses to discriminate on the basis of freedom of commerce. In July 1936, Fred Christie and two friends went to the York Tavern attached to the Montreal Forum to have a beer. The staff refused to serve them because Christie was Black. Christie sued, eventually bringing his case to the Supreme Court, which ruled that the York Tavern was within its rights to refuse to serve people on the basis of race. The case reveals an era of legalized racism, while its facts hide the subtle ways that racism operated in early 20th-century Canada.

Viola Desmond’s Trial

In the morning, Viola Desmond was brought to court and charged with attempting to defraud the provincial government based on her alleged refusal to pay a one cent amusement tax (i.e., the difference in tax between upstairs and downstairs ticket prices). Even though she had indicated when she was confronted at the theatre that she was willing to pay the difference between the two ticket prices and that her offer had been refused, the judge chose to fine her $26. Six of those dollars were awarded to the manager of the Roseland Theatre, who was listed in the court proceedings as prosecutor. Throughout the trial, Desmond was not provided with legal representation or informed that she was entitled to any. Magistrate Roderick MacKay was the only legal official in the court; no crown attorney was present.

At no point in the proceedings was the issue of race mentioned. Still, it was clear that Desmond’s real offence was to violate the implicit rule that Black persons were to sit in the balcony seats, segregated from White persons on the main floor. When asked about the incident by the Toronto Daily Star, MacNeil maintained that there was no official stipulation that Black persons could not sit on the main floor. It was “customary,” he said, for Black persons to sit together on the balcony. Nonetheless, it was common knowledge among the Black community in New Glasgow that seating at the Roseland Theatre was racially segregated.

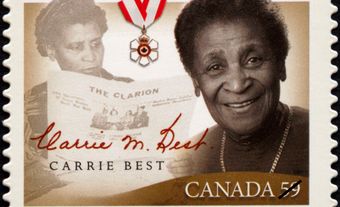

Desmond’s husband, Jack, had grown up in New Glasgow and was not surprised when Viola told him about her treatment at the Roseland. Like many other Black Nova Scotians who had grown accustomed to the racist attitudes that prevailed in the province, he was inclined to let the issue rest. “Take it to the Lord with a prayer,” was his suggestion. Others in the community were less accepting; the Nova Scotia Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NSAACP) raised money to fight Desmond’s conviction, and Carrie Best, the founder of The Clarion, the province’s second Black-owned and operated newspaper, took a special interest in the case. Best had had a similar experience at the Roseland Theatre five years earlier and had unsuccessfully filed a civil suit against the theatre’s management. The Clarion closely covered Desmond’s story — often on the front page.

Did you know?

In December 1941, Carrie Best heard that several high school girls had been removed by force from the Roseland Theatre. The Black teens had tried to sit in the Whites-only section. After she explained to the Roseland’s owner, Norman Mason, that the theatre’s policy was racist, she visited the theatre with her son, Calbert, and sat downstairs. Best and her son were arrested and charged with disturbing the peace. Afterwards, Best filed a civil lawsuit against the Roseland for racial discrimination; however, the owner’s right to exclude anyone service won out over the bigger issue of racism in court.

On the advice of the doctor who examined the injuries that resulted from her arrest, Desmond contacted a lawyer in order to reverse her charge. Legal scholar and historian Constance Backhouse mentions that, at the time, the legal nature of racial discrimination had yet to be settled in Canada (see Fred Christie Case). While judgements varied from case to case, two competing principles prevailed: freedom of commerce, and an individual’s right to freedom from discrimination based on race, creed or colour. Neither principle took precedence over the other. In addition, no court in the province had ruled on the illegality of racial discrimination in hotels, theatres and restaurants.

Given the ambiguity of the situation, Frederick Bissett, Desmond’s White lawyer, chose not to take on the violation of Desmond’s rights: neither her basic civil rights, nor her rights to a fair trial with competent legal representation (see also Civil Liberties). Instead, Bissett had the court issue a writ identifying Desmond as the plaintiff in a civil suit that named MacNeil and the Roseland Theatre Co. Ltd as defendants. It sought to establish that MacNeil had acted unlawfully when he forcibly ejected Desmond from the theatre, which would entitle her to compensation on the grounds of assault, malicious prosecution and false imprisonment.

The suit never made it to trial, and Bissett later applied to the Supreme Court to have the criminal conviction put aside. The case was considered by Nova Scotia Supreme Court Justice Maynard Brown Archibald, who, on 20 January 1947, ruled against Desmond on the grounds that the decision of the original magistrate should have been appealed to the County Court. As the 10-day deadline for filing an appeal to the original conviction had passed, the conviction stood.

After the Supreme Court decision, legal action on the matter stopped. Bissett did not bill his client, which allowed the NSAACP to use the funds raised for legal fees to continue their fight against segregation in Nova Scotia. Change didn’t happen quickly, and it is difficult to say whether Desmond’s experience had a direct effect on the quest for racial equality in the province. Nonetheless, her choice to resist the status quo, and the level of community support she received (e.g., from The Clarion and the NSAACP), reveals a mobilization for change among members of Nova Scotia’s Black population who were no longer willing to endure life as second-class citizens. In 1954, segregation was legally ended in Nova Scotia thanks in large part to the courageous determination of Viola Desmond and others like her who fought to be treated as equal human beings.

It is difficult to know what Viola Desmond felt about her brave stand and its aftermath. Eventually, and perhaps due to her experience with the Nova Scotia legal system, her marriage fell apart. She decided to abandon her business and move to Montreal and then New York City. She died on 7 February 1965 in New York.

Significance and Legacy

Decades after her death, Viola Desmond’s story began to receive public attention, primarily through the efforts of her sister Wanda Robson. In 2003, at the age of 73, Robson enrolled in a course on race relations in North America at University College of Cape Breton (now Cape Breton University) taught by Graham Reynolds. In the course, Reynolds related the experience of Viola Desmond, prompting Wanda to speak out. With the help of Reynolds, she began a prolonged effort to tell her sister’s story, including the publication of a book about her sister’s experience, Sister to Courage (2010).

On 15 April 2010, Viola Desmond was granted a free pardon by Nova Scotia Lieutenant-Governor Mayann Francis at a ceremony in Halifax. The pardon, accompanied by a public declaration and apology from Premier Darrell Dexter, recognized that Desmond’s conviction was a miscarriage of justice and that charges should never have been laid. At the formal ceremony, Minister of African Nova Scotian Affairs and Economic and Rural Development Percy Paris said, “With this pardon, we are acknowledging the wrongdoing of the past,” and “we are reinforcing our stance that discrimination and hate will not be tolerated.”

In 2010, the Viola Desmond Chair in Social Justice was established at Cape Breton University, and in 2012, Canada Post issued a postage stamp bearing her image. A Heritage Minute relating Desmond’s story was released during Black History Month, in February 2016.

On 8 March 2016, International Women’s Day, the Bank of Canada launched a public consultation to choose the first Canadian woman to appear on the face of a Canadian banknote. On 8 December 2016, it was announced that Desmond would appear on the face of the $10 note (see Women on Canadian Banknotes).

In 2017, Desmond was inducted to Canada’s Walk of Fame under the Philanthropy & Humanities category. In January 2018, she was named a National Historic Person by the Canadian government. On 6 July 2018, a Google Doodle telling Desmond’s story was released in Canada in celebration of her 104th birthday.

On 19 November 2018, the $10 bill featuring Viola Desmond was released. The bill was Canada’s first vertical banknote (see Money in Canada). It also features a map of the North End of Halifax, where Desmond lived and worked, and an excerpt from the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms: “Every individual is equal before and under the law and has the right to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination.” The Canadian Museum of Human Rights is featured on the back of the bill.

In February 2019, the Royal Canadian Mint announced the release of its first Black History Month coin, a pure silver coin featuring an engraved portrait of Viola Desmond. In April 2019, the $10 bill featuring Desmond won the International Bank Note Society’s Banknote of the Year Award for 2018.

The government of Nova Scotia repaid an adjusted amount of Viola's fine to her sister in February 2021. Wanda used the $1,000 to fund a scholarship at Cape Breton University.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom